Auguste Rodin’s “Iris, Messenger of the Gods” – What do you feel?

The way we feel about artistic creations can change over time, whether because of the accumulated personal experience or the prevailing historical context. Feelings are inherently subjective and depend on a variety of factors. However, works of art themselves usually remain static, they do not change. What also does not change is the fact that the viewer looking at them feels something, regardless of the nature of that feeling.

An art historian’s experience report

French sculptor François-Auguste-René Rodin (1840, Paris – 1917, Meudon) is by now world-famous, and his life has long since been depicted in novels, films and modern popular culture. In particular, his passionate and ultimately tragic relationship with Camille Claudel continues to evoke a profound emotional response.

Throughout his career, the artist who used Auguste Rodin, the short version of his full name, was indeed able to impressively capture a wide range of emotions: love and passion in The Kiss (1882) , inner tension, fear and shame in the famous monument The Burghers of Calais (1884-1889), reflection and inner struggle in The Thinker (1880), despair and agitation in The Gates of Hell (1880-1917), and creative inspiration in his sculptures in memory of Honoré de Balzac (1898) and Victor Hugo (c. 1891-95). The last two works testify to Rodin’s immense admiration for these writers. The typical, seemingly vibrating surface design and finish, as well as the expressiveness of the facial features, reinforce the impression of dynamism and liveliness, allowing for a strong emotional experience.

The French sculptor clearly had a talent for depicting emotions. But what about the emotions of the viewer, both now and in Rodin’s time?

I would like to tell you a little anecdote from my own life: in the early 2000s, I was in my final year of high school, and one of the compulsory subjects in the final art exams was the work of Rodin, along with those of Michelangelo and Max Beckmann. I was familiar with Rodin’s most famous sculptures and was a little taken with the marble version of The Kiss, but my additional research on Rodin led me to a sculpture that bore my first name (Iris) and the subtitle „messagère des dieux“ (engl. Messenger of the Gods). I was excited, expecting that this Greek winged goddess, who was Hera’s personal messenger and could travel on a rainbow bridge to the depths of the underworld, would also be angelically beautiful. In my imagination, I saw a white marble sculpture full of light.

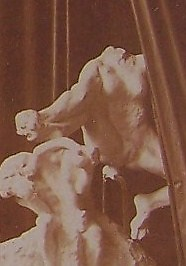

But when I opened the relevant book chapter, there it was…Iris, Messenger of the Gods (c. 1895) was actually a bronze. The messenger of the gods, in its current confrontational posture, is depicted as a naked female body, a fragmentary torso with the left arm and head removed, legs spread wide and the smooth genitalia expressively formed. Iris also lacks a pair of wings. The sculpture in the Musée Rodin in Paris and the cast in the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart are mounted on a support at the back, so that when viewed from the front, the figures appear to have been impaled in the groin. My first feeling was one of horror and utter dismay, and I asked myself: Is this sculpture really meant to be misogynistic in the way I perceive it when I look at it at this very moment? And what must have been the perception at the time it was created?

By the end of the 19th century, nudity alone could no longer have been offensive, since the first life-size post-antique nudes had already been created during the Renaissance. A feminist perspective was largely unknown – Simone de Beauvoir (1908, Paris – 1986, ibid.) was not born until 13 years after the completion of Iris, Messenger of the Gods, and her universally acclaimed The Second Sex was not published before 1949, some 54 years after the completion of Rodin’s sculpture.

The freestanding sculpture Iris, Messenger of the Gods was developed within a broader context. Originally, Iris was part of Rodin’s second proposal for a monument to Victor Hugo for the Panthéon in Paris. A first version, cast in bronze, remained in the Musée Rodin in Paris. A later plaster cast, on display in Rodin’s former house in Meudon, shows the messenger of the gods lying in the clouds, which form a niche in which the figure of the writer is placed. The messenger of the gods, her genitalia visible, hovers above the head of the writer symbolising the moment of fruitful inspiration during the creative process: the messenger of the gods as mediator between divine creativity and the visual arts.

From the 1890s onwards, Rodin’s drawings often show women opening their thighs as if literally offering them to the viewer. Masson and Mattiussi see this as the product of Rodin’s almost boundless curiosity about the female body (Masson, Raphaël and Véronique Mattiussi: Rodin, Paris, 2004, p. 186). Are we therefore dealing here with an unemotional fact-oriented, scientific thirst for knowledge, and not just lust? The artist’s true intention probably lies somewhere in the middle. And I have to say that the additional knowledge I gained about the sculpture made me reconsider my initial opinion and my personal dislike of its confrontational posture: Iris, Messenger of the Gods is captured as she swoops through the air. Rodin tried to achieve the feeling of weightlessness by shifting the centre of gravity and using an iron bracket at the back of the sculpture to support its weight.

So much about Rodin’s intentions. But how did his contemporaries react to the work?

Iris, Messenger of the Gods was a semi-public sculpture that Rodin exhibited only on three occasions in his lifetime: in Munich in 1898, in Paris in 1900 and in Rome in 1913. The only way to catch a glimpse of this sculpture was to visit one of the exhibitions and find it among over 100 other exhibits, or to visit Rodin’s studio in person. An anonymous contemporary photograph shows Rodin presenting his sculpture in the safety of his studio, letting it emerge behind a heavy curtain, as if alluding to the embarrassment of the viewers. It seems more likely, however, that Rodin cultivated his reputation as a lecherous artist who enjoyed entertaining the masses and satisfying their desire for sensation by creating works of art to match.

Indeed, the reactions of Rodin’s contemporaries are mostly favourable. Gustave Geffroy, for example, in a letter to the master in 1907, calls Iris, Messenger of the Gods “l’adorable Iris“. Léon Maillard, who saw Iris during a guided tour of Rodin’s studio, praises the work and describes it in detail in his book „Auguste Rodin, Statuaire, Études sur quelques artistes originaux”. The sculptor Aristide Maillol was also enthusiastic about the bronze, preferring it to Rodin’s other works. Germany was much more prudish at the time, so the press reviews and comments there were either neutral or negative.

When Iris, Messenger of the Gods was first shown to the public in 1899, on display were also controversial and scandalous works such as the much-criticised monument to Honoré de Balzac. In the context of his erotic drawings, Rodin himself was critical of the furore that always preceded his exhibitions. “It is certainly not the intention to announce the exhibitions of [one’s] drawings in a blaze of glory. On the contrary, they must be carefully protected, so that the public does not take to the barricades”, he said.

In summary, Rodin’s sculptures express emotions either through their facial expressions, their posture and/or their surface design and finish. On the other hand, they evoke strong emotions, be they positive or negative. If I had my current experience, I would undoubtedly be much less shocked than I was when I first saw Iris, Messenger of the Gods – at the age of 18 and without any knowledge of art history. Today, I see this sculpture as a paean to the female body and to creative productivity – without denying the obvious male gaze perspective. When we perceive works of art, our emotions don’t have to be black and white, we can allow ourselves to see in shades of grey.

Written by Iris Haist in German.