The Poetic Potential of Sound

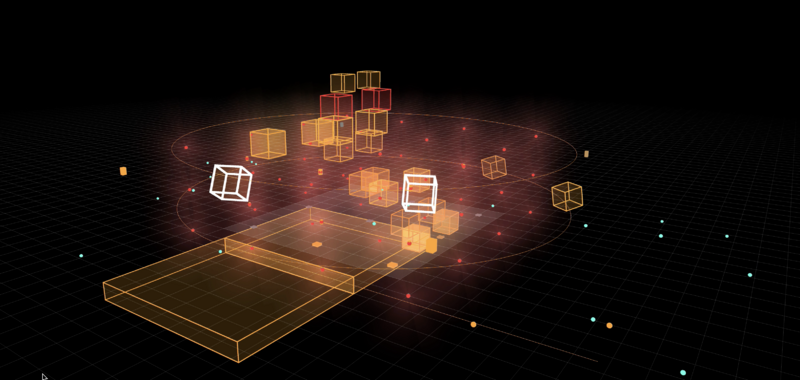

Sound art is a relatively new shoot on the ever-expanding stem of the arts. Especially the digital revolution in sound technology in recent decades has created many new possibilities, such as ‘object-based audio’, a technique often used by sound artist and composer Casimir Geelhoed (NL, 1995). With a few buttons on his iPad, he can control a large number of virtual sound sources simultaneously during a live performance. Groups of sounds spread through the room like swarms, flow around like an overwhelming vortex, or fly up into the air. This creates an abstract play of forms in a space that interfaces with choreography, architecture, and sculpture.

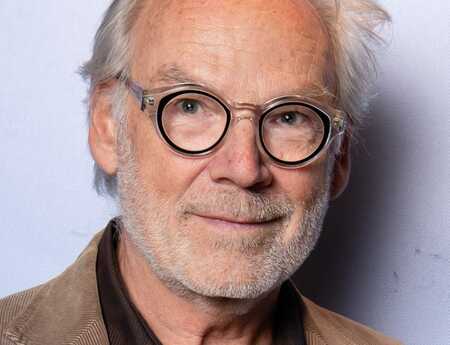

Geelhoed defines music as ordered sound and explores in his work the expressive relationships between software and sound. He builds his own digital instruments, which he uses for his compositions and during performances. Geelhoed's sound performances (at, among others, the spatial sound stage MONOM Berlin, the Stedelijk Museum Schiedam, and during the FIBER Festival in Amsterdam) are mainly spatially oriented. As a composer and sound artist, he belongs to the absolute Avant Garde. We have a talk on a sunny Thursday afternoon in Rotterdam, where he has his studio.

History of sound art

In sound art, anything that makes sound can be part of a work of art. The art form dates back to the early inventions of futurist Luigi Russolo, who built between 1913 and 1930 sound machines that mimicked the clatter of the industrial age and the thuds of warfare. Visual artists and composers such as Bill Fontana used kinetic sculptures and electronic media in the 1950s and 1960s, overlapping live and pre-recorded sounds. Consider also Marcel Duchamp’s composition Erratum Musical: three voices singing notes that were pulled out of a hat. Or John Cage, who composed 4'33″ in 1952, a musical score of four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence.

Sound art is also often accompanied by visual art, performances, and the craft of home-made instruments. Take sound artist Tarek Atoui (*1980, Beirut, Lebanon), who builds his own instruments and whose retrospective is now on show at SMAK in Ghent. Atoui is known for his extraordinary sonic sculptures, in which he integrates sound, image, matter, space, and time. Casimir Geelhoed leans less on the visual arts than Atoui, concentrating more on composing digital sound productions using technical possibilities such as sound synthesis and object-based audio.

Fear, fragility, and transience

As a composer, Geelhoed is interested in the transformations of sound over time. What does it mean when a sound element emerges, crumbles, slowly dies out, or is overwhelmed by another sound element? Through the abstraction of the medium, personal expressions become universal. In doing so, Geelhoed uses self-developed software and is interested in the poetic potential of sound material transformed by digital means. Themes that recur in his compositions: overstimulation, anxiety, fragility, and transience.

You are a composer and a software developer. For whom do you develop software?

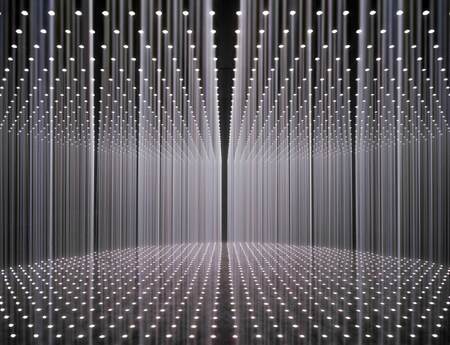

I work for 4DSOUND, a studio that explores spatial sound as a medium. I am one of the developers of the object-based audio software 4DSOUND, which is used by artists and studios in several places around the world. I also create new software tools for specific performances and installations. With this software, I try to enable new forms of expression for myself, outside the beaten path of existing technologies. On the sound stage at MONOM in Berlin, I have performed my own compositions several times. For instance, in the performance Scatter, Swarm, Sublimate (premiere 2022 and performed on MONOM's 57-speaker system in Berlin), I made expressive use of ‘particle systems’. With a few buttons on my iPad, I can control a large number of virtual sound sources simultaneously in a live performance, including algorithms inspired by systems from nature. The contrast between order and chaos, stability and instability, and the direction of flowing sound thus become playable musical parameters. Groups of sounds spread through space like swarms, flow around like an overwhelming vortex, or fly up into the air.

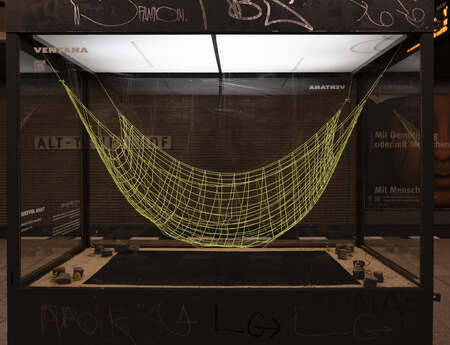

We talk further about the uses of sound art and about the composers of contemporary classical music who include all kinds of sounds in their compositions, which come from simple objects such as cowbells (Mahler), falling water (Tan Dun, Water Passion after St Matthew), or a tray of wine glasses that is being thrown on the ground (Ligetti). Often, these are borderlands in music and sound. A fine example was Geelhoeds and Anni Nöps' sound installation Borderlands, which could be experienced at the Stedelijk Museum Schiedam earlier this year during the exhibition Ekstasis, a universe of light and sound.

Can you tell me more about Borderlands and your performances across Europe?

I made the installation Borderlands (2023) in collaboration with sound artist Anni Nöps. We used object-based audio and channel-based audio in a 20- to 30-minute loop. For us, Borderlands was an attempt to create an area ‘on the border of perception’. The concept of borderlands is reflected in this work in several ways. As a visitor to the attic of the museum, you were confronted with only darkness; it was the end of the exhibition. In the halls downstairs, you discovered a real visual world with all kinds of installations; up in the attic you entered an imaginary auditory world of sound art and music. Virtual acoustics and spatial sound were used to create the illusion of an infinite auditory space unfolding in the dark, populated by dreamlike sounds. It was extraordinary of the museum to integrate our artwork, which consists only of sound, into the Ekstasis exhibition.

How was Borderlands technically constructed?

The sound material itself constantly oscillates between realistic and fictional; many of the natural-sounding sounds (such as the surf of the sea and the crackling of a fire) were created synthetically, using computer codes. We edited natural sounds by extensively using sound effects. As a visitor, you could lie on the floor on cushions. It was unclear what was real and what was virtual. Real environmental sounds, such as the actual rain falling on the roof or the church bells ringing in the museum's chapel, became part of the sound composition.

Do you and Anni Nöps work together more often?

Certainly, in our joint work, we are much engaged in creating ‘listening spaces’ that invite introspection and attentive listening. We perform together and organise events through which we try to bridge the gap between contemporary composed music and the world of electronic music.

And what about your object-based audio?

This is a combination of specific speaker systems and software technology that allows sound to move freely through space as a virtual sound source. Sounds can be positioned anywhere in the room. Sounds can also be simulated to appear to come from outside the room. Sound, as we experience it in everyday life, is spatial and three-dimensional. Our hearing is very good at registering location, space, and movement. By working with object-based audio, you can compose sound in a way that is as close as possible to how sound naturally behaves. It is a richer and more intuitive way of working with sound, which brings with it a vast palette of new expressive possibilities. You then think not only in common musical dimensions but also in an abstract play of forms in space, which interfaces with choreography, architecture, and sculpture.

Further information:

www.smak.be/nl/tentoonstellingen/tarek-atoui

The interview was conducted by Etienne Boileau in English.

Cover picture: Monom. Photo: Becca Crawford