Sensing Sculpture

How does hot bronze smell before it becomes art? How does a sculpture made out of mist feel on my skin? How do sound installations sound when the volume is switched off? Are there such things as artworks that are sweet? When does a sculpture touch me, and when am I allowed to touch a sculpture? Questions like these and many more will be explored this year as we dedicate ourselves to the topic of Sensing Sculpture.

After having tackled major social issues in the last two years – Sculpting Society in 2022 and Sculpture and Climate Emergency in 2023 – we would like to head back to our roots in 2024. Back to the the artwork. How does it taste, how does it smell, how will we see it, and how will it feel.

Through our articles in our magazines and our events, we seek to make sculpture a perceptible experience for all of our senses and to discover the underlying stories of these sensually tangible works. From Barcelona to Berlin, all across Europe, we want to sense sculpture. As a taster for this coming year, enjoy a small digital exhibition of artworks for your senses.

Touch: Judith Mann and Tamara Jacquin

Mist. It is these very finest droplets of water, so familiar to us from everyday life, that are Judith Mann's working material. Alongside electromagnetism, lightning, and other natural phenomena, she draws the viewers of her work closer to this most delicate form of rain and makes the mist a tangible experience. In places and at times when no grey cloud would naturally touch the ground.

Hearing: Benoît Maubrey

Benoît Maubrey's chosen material consists of found and recycled electronic devices. In his installations, such as SHIPWRECK and SPEAKERS ARENA, visitors are invited to shape the sound themselves. Via Bluetooth, they can play songs or messages or connect directly to the loudspeakers using a microphone. The installation is transformed into a concert hall.

Alongside large-scale works in the public space, Benoît Maubrey also creates sounding clothes that are equipped with amplifiers and loudspeakers.

He says of his own work: “Artistically, I use loudspeakers much in the same way that a sculptor uses clay or wood: as a modern medium to create monumental artworks with the added attraction that they can make the air vibrate (‛sound’) around them and create a public ‛hotspot’.”

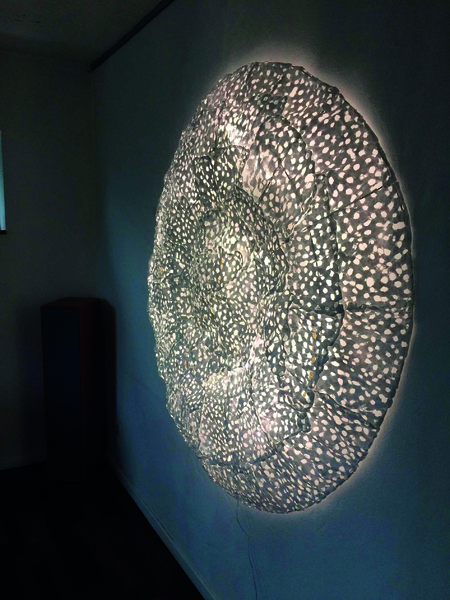

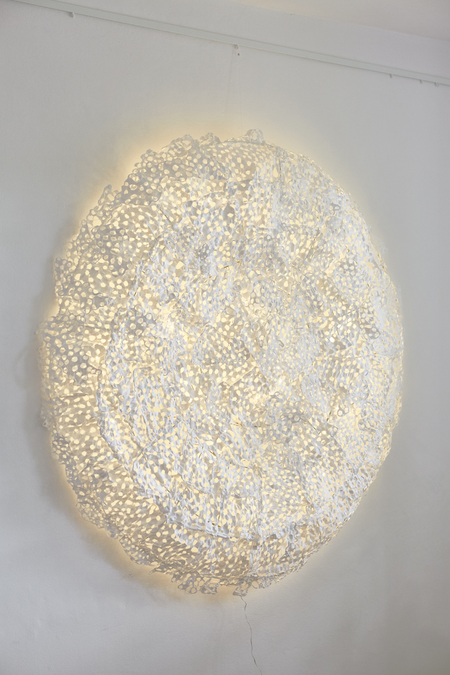

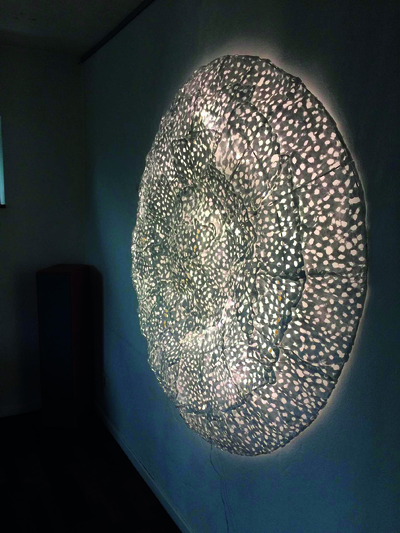

Sight: Verena Friedrich

Verena Friedrich painstakingly burns holes in a non-woven fabric using the flame of a candle. The resulting work, contemplation, invites you to dwell and reflect on yourself. It is only through the holes that the light is able to permeate the work, and thus it becomes visible.

Taste: Félix González-Torres

As such, he constantly challenges curators with the task of reinterpreting his work. If at all and how often are the candies replenished during an exhibition, on what area are they presented, and how long is the ideal weight maintained, it is entirely up to the makers of the exhibition, as was impressively seen and tasted last year at the Munich Museum Brandhorst as part of the exhibition Future Bodies from a Recent Past.

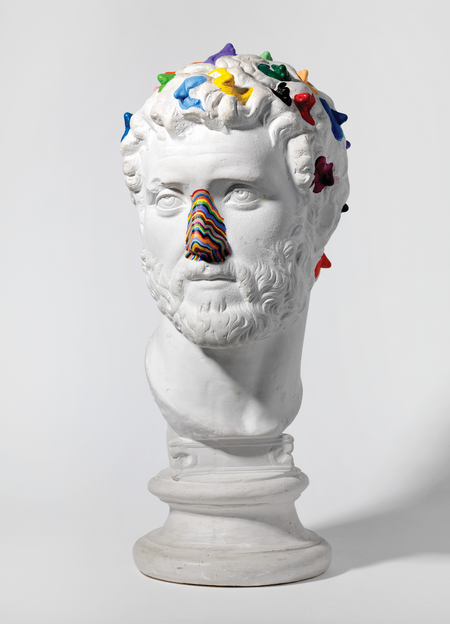

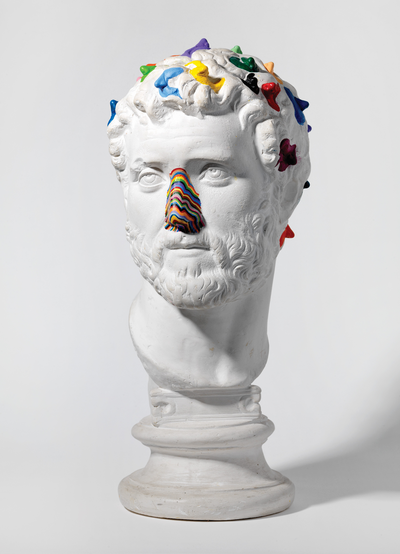

Smell: NASEVO

Looking forward to a year full of further, sensually perceivable, three-dimensional art along with exciting new experiences under our theme of Sensing Sculpture!