The Poetry of Motion: Sculpture Network’s Online Club “Moving Sculptures II”

On the second evening dedicated to kinetic art, Sculpture Network Online Club brought together three artists whose works question not only how sculpture moves, but why it should.

Moderated by Dutch curator and SN Chairperson Anne Berk the evening started by tracing the lineage of the kinetic impulse: from the Russian Constructivists who liberated form from stillness to László Moholy-Nagy’s light-space modulators and beyond. Today, the artists gathered — Bart Nijboer, Christina Sporrong, and Willi Reiche — show that motion in sculpture has evolved into a rich language of its own, combining craft, technology, nature, and humour. The result is not merely mechanical choreography, but an expanded meditation on life itself.

Bart Nijboer: Nature’s Hidden Rhythms

The evening opens with Dutch artist Bart Nijboer, who appears on screen surrounded by the calm of his studio. His video sequence unfurls a series of delicate, quietly mesmerizing works — machines that breathe, pulse, and sway with a slow and deliberate rhythm. Nijboer’s fascination lies in the invisible movements of nature: “When nature grows,” he says, “it moves in a tempo that we cannot see. I wanted to reveal a little of that hidden motion.”

Trained in Arnhem, Nijboer’s practice fuses an engineer’s precision with a poet’s sensitivity. His sculptures often juxtapose natural forms and human constructions, revealing what he calls “the clash between what we make as humans and what is there in nature.” Metal — his preferred medium — becomes strangely organic under his hand, shaped into forms that breathe and respond to light. In Lux-Aquipass (Light Catchers), spiraling structures echo the tendrils of tomato plants seeking sunlight, projecting grass-shadowed patterns at night. Nature and machine meet in an impossible mimicry: the artist does not copy the natural, but reminds us of our distance from it.

Later works, such as his “breathing armor” — a metallic torso rising and falling with slow respiration — speak of vulnerability and resilience. The contrast between the material’s hardness and the body’s fragility becomes a metaphor for humanity’s uneasy relationship with the natural world. “It’s like a hollow leaf,” Nijboer reflects, “both fragile and strong.” His final work, soon to be installed in a pond in his hometown of Driebergen, returns this dialogue to its origin — water, reflection, and the cycle of growth and return. For Nijboer, motion is not spectacle; it is reverence.

Christina Sporrong: Fire, Steel, and the Spectacle of Scale

If Nijboer’s motion is meditative, Christina Sporrong’s is incendiary. The Swedish-American artist greets the audience with humor and energy: “I lived in America most of my life,” she laughs, “everything is much bigger there.” Her sculptures indeed operate on the scale of performance, fusing engineering, theatre, and pyrotechnics into immersive experiences. Sporrong’s world is one where art breathes fire — quite literally.

Her first major kinetic installation, Cage Pulse Jets, transforms industrial technology into a sonic sculpture. Inside a massive birdcage, she mounted five homemade pulse-jet engines, each tuned to a different tone. The public could activate them, orchestrating a collective composition of light, sound, and vibration. “It was cacophonous,” she recalls, “but somehow there was melody in it.” The project, shown at Glastonbury and Burning Man, captures the primal joy of noise — an ecstatic merging of danger and play.

The artist credits the Burning Man community as a catalyst for her large-scale works. “It’s not just a festival,” she explains, “it’s a gathering of people who bring art.” Through Burning Man’s grant program, Sporrong realized monumental projects such as The Flybrary (2019) — a twelve-meter-tall head transformed into a public library. Visitors climbed inside the structure, reading among hundreds of donated books while metal “book birds” flew from the open skull. Amid the noise and dust of the Nevada desert, it offered a sanctuary of thought. “There was this silence,” Sporrong recalls. “People went in and started reading. It was beautiful.”

Equally memorable is her Tarantula, a massive spider made of forged steel and interactive lights that respond to sound — a fusion of natural movement and electronic rhythm. Sporrong’s recent work in southern Sweden turns inward again: inspired by decaying trees and the slow metamorphosis of forest life, she is now exploring “arrested movement” — the illusion of motion in stillness. Her upcoming women’s residency in Skåne will open this exploration to others, offering a forge, studio, and open fields for artists who work with unconventional materials. “I love scale,” she admits, “because it forces you to engage. You can’t just walk by.”

Willi Reiche: Machines with a Soul

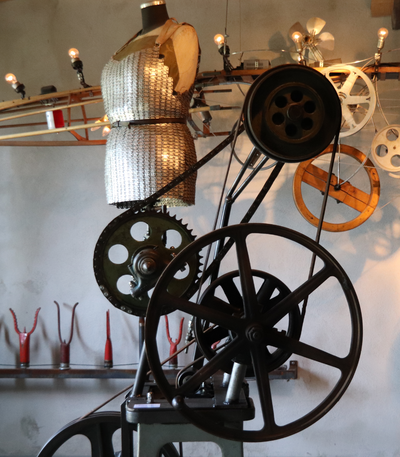

The evening concludes in Germany, inside Willi Reiche’s Kunstmaschinenhalle, an industrial cathedral filled with 100 kinetic assemblages. In three short films, the artist takes us through his world of mechanical humour and poetic absurdity — a world where movement becomes metaphor. “It’s not about productivity,” he says, “but about aesthetics. My machines awaken discarded objects to a new life.”

In contrast to the digital invisibility of modern technology, Reiche’s machines reveal their workings with disarming honesty. Cranks, cams, and counterweights are left exposed; nothing is hidden. “I like things that move and shouldn’t,” he smiles. His Nusa – Der Lichtkegel (The Cone of Light) brings together more than 100 light bulbs of varying voltages in a rotating luminous structure. The piece, originally featured in a Hornbach artist series, embodies the playfulness that underlies all his work: serious craft paired with childlike wonder.

Reiche calls himself a “tinkerer of the useless,” but his machines hum with meaning. They remind us of a time when technology was visible, comprehensible, and tactile. Berk notes the nostalgia for an age when people could still understand the mechanisms that powered their world. Reiche agrees: “Today, technology is hidden. You can’t repair it. My machines show how things move — and that gives joy.”

Sculpture in Motion, and in Conversation

What connects these three artists, beyond their use of movement, is a shared fascination with transformation. For Nijboer, it is nature’s invisible growth; for Sporrong, the transformation of energy into experience; for Reiche, the rebirth of forgotten materials. Each, in their own way, challenges the boundary between the organic and the mechanical, between sculpture and performance, between stillness and time. Kinetic art, once the avant-garde’s flirtation with modernity, has become a language for our age of flux. It asks us to look — and keep looking — as forms change, breathe, and decay.

When the evening ends, one feels that movement has not stopped — it has merely shifted to another scale. As Anne Berk said at the outset, the question remains: Why do we want sculptures to move?

Perhaps because movement, more than any other gesture, reminds us that we are alive.

The event report was written in English with the help of ChatGPT and edited by our editorial team.