Andreas Mühe at the Galerie Bastian and the Kunsthaus Dahlem

"So how was Berlin?” My daughter combined her question with a certain lack of understanding as to why I had to travel from Munich to the “big city” for just a few hours. “Challenging-demanding”, I replied. Two exhibitions by photographer Andreas Mühe were the focus of a Dialogue organized by Sculpture Network.

Anemone Vostell, the Berlin-based coordinator of Sculpture Network, moderated the event in an informative and entertaining way – without excluding the non-experts by using too much artist jargon.

Andreas Mühe's exhibition “Freitag – den 13.” at the Galerie Bastian, running until 16 November 2024, features scenes from West German prison cells and an East German youth club. Mühe's photographs confront the viewers with the starting and ending points of radical political actors and perpetrators of violence; murderers – as he puts it. The photographs show the prison cells of Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin and Jan-Carl Raspe in Stuttgart-Stammheim as well as the youth club in Jena where Beate Zschäpe, Uwe Böhnhardt and Uwe Mundlos supposedly first met.

The initial impression is misleading, though. Neither the settings in the prison cells of the RAF terrorists nor the pictures from the youth club show the reality. Mühe takes his photographs in a studio. He does not show how things were, but he stages how they could have been. The performing actors are hidden behind masks; the death masks of the RAF terrorists – a perfidious game. In 1977, Gudrun Ensslin's father requested that these masks be made, and forty-five years later, these same masks were offered to Andreas Mühe. Today, they are stored in his safe.

Mühe's close-ups are reminiscent of history paintings that do not show a view of the actors but a staged, constructed view of them. Mühe exposes the actors, he shows an option, a possibility. There might have been other options, perhaps. “Nobody”, says Mühe, “is born a murderer”. There is always a second face – and another story. But which? This is something everyone has to decide for themselves.

Mühe's striking photographs are challenging given the highly aesthetic environment of the Gallerie Bastian. The gallery is an immaculately elegant pavilion designed by British architect John Pawson. With its clear basic form, the gallery is a container for art – nothing missing, but also nothing to add. Nothing less will do.

The narrow windows stretch from the floor to the roof. Nothing here distracts from the art – normal life is far away. And although the outside can be seen, it cannot be experienced. The approach is clear: this space will never take precedence over the art on display. Here, art is art – and in these well-proportioned rooms, everything else is something different. The architecture is charged with the evident value of the selected materials – natural stone, stainless steel, and glass. Andreas Mühe's accurate image compositions rise in a perfect manner to the challenge of this space. What is reality, what is staging, what is expectation?

Bunkers as Real Spaces of History

Andreas Mühe's exhibition Bunker – Real Space of History that runs at the Kunsthaus Dahlem until 6 October 2024 is comparable but still very different. The Kunsthaus resides in the former state studio of sculptor Arno Breker, prestigiously located on the outskirts of Grunewald, in the – then and now – “elite” neighbourhood Dahlem. This was the place where Breker's works for the monumental structures of the new Reich capital, Germania, were to be created. Emilio Vedova, Bernhard Heiliger and Wolf Vostell worked here after the Second World War, and, until 2014, holders of a scholarship awarded by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) could use the ateliers.

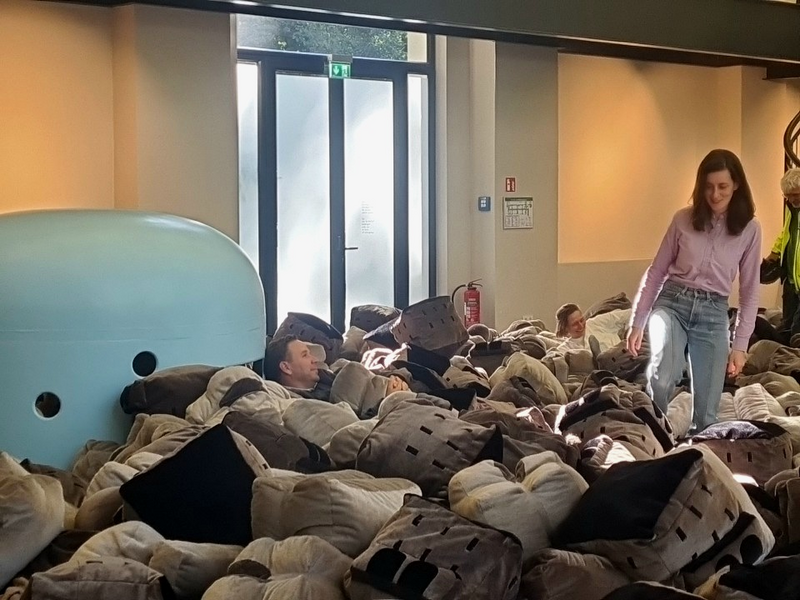

The first exhibition room displays a type of set design consisting of 6,000 plush fabric bunkers. Andreas Mühe had the Spielzeug Manufaktur in Bad Kösen produce eleven types of historical bunker buildings of a size suitable for children's hands. Colourful elements – true-to-the-original casts of DDR playground equipment – are placed amidst the grey fabric landscape. The cylinder-shaped structures are reminiscent of the so called “one-man-bunkers” installed by the ten thousandth in the German Reich during the Second World War and aimed at conveying the message that humans can find protection there – an imaginary, deceptive promise. Mühe's challenge to the visitors: leave the bunkers to the children, or have a bunker pool instead of a ball pool?

The cultural-philosophical and the art-historical context steps to the fore in the next exhibition room. Citations from the book Bunker Archaeology of French philosopher Paul Virilio published in 1975 cover the walls, next to them works by various artists. Given the present-day technology of war and military weapons, to Mühe, the assumption that bunkers can be protective spaces appears obsolete. Instead, he sees bunkers as documents of the devastating force of weaponry that can destroy any life, no matter how safe it may seem.

The article was written by Willy Hafner in German.

Photos by Willy Hafner and Anemone Vostell.