Territory, Marginalisation, and Humanity are being renegotiated – 13th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art

The 13th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art bears witness to humanity's woundedness, to contexts of injustice in other countries, and to sites of escape and exile. Sounds “gruelling”, but in many places it is above all deeply enriching, profound, and has eye-opening power, if we are able to get involved.

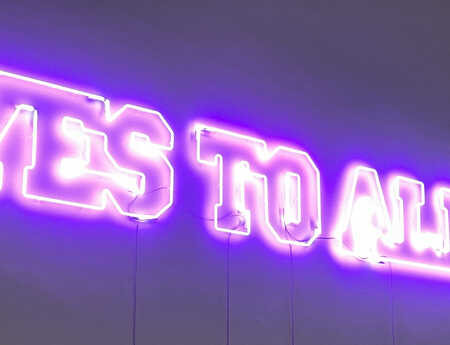

The multifaceted program offers opportunities for participation (stepping into action against one's own often resonating helplessness), and the plentiful artistic spaces that have been created empower us to change perspectives. The works explore the question of which artworks have been created under mortal danger or in massive existential distress or after displacement. Not instructional, but under the sign of the roaming fox: curator Zasha Colah selected the quiet, barely domesticable creature as the symbol of her biennial. Foxes suddenly emerge from the shadows, and here they symbolise an art that follows its own uncontrolled paths – unpredictable and beyond all control. In their works, the artists (within the local institutional protected space) use a variety of languages to embody resistance or flight as well as belonging, remembrance, and inner processing. Their at times utopian ideas for peace and universal humanity and dignity work through the final outcome. Acting against indifference and for the visualisation of the Other and of real conflicts. The question remains as to how we here in our Western and – if we are honest – rather exhausted society are able to cope with this.

The Offering

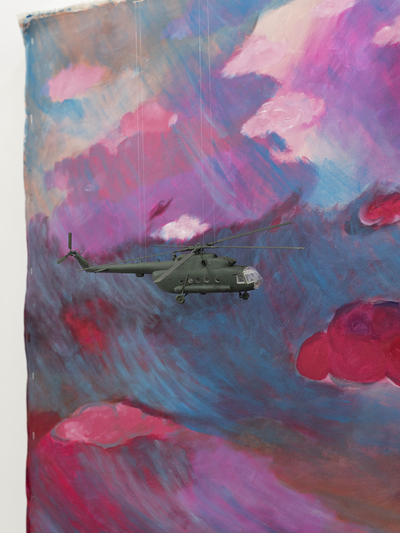

Under the heading Passing on the Fugitive, the two curators, Zasha Colah and Valentina Viviani, are presenting over 170 works at four exhibition venues by 40 artists, mainly from Southeast Asia, in particular Myanmar, as well as from Argentina, Turkey, Bosnia, and other regions where violence is an integral part of everyday life. The exhibition title remains somewhat vague – perhaps even misleading. But it makes it all the clearer (in the catalogue text) what it is essentially about: it is about the resilience of art and how artworks assert their own laws in the midst of repressive systems, under the weight of arbitrary laws, persecution, militarisation, and ecological destruction – keeping thought processes alive where others fall silent. The exhibition is deliberately focusing on those breaking points in our presence where society has to renegotiate itself. Many works address one of the oldest conflicts of mankind: the struggle for territory. In this context, we also find a – literally remarkable – work of sculpture by Margherita Moscardini.

While at the same time, the exhibition challenges its visitors to leave behind all familiar viewing habits and a conception of art shaped by the West. As at any biennial, it is about getting involved – with other perspectives, with not-knowing, with probing questions with no immediate answers. To listen, to observe, to endure complexity and the Other – or have we forgotten how to do this in our world steeped in images and discourse? Zasha Colah even calls for humour and speaks in the exhibition catalogue of a “mental ability” – the power of humour to protect us from bitterness even under the most adverse conditions. In doing so, she also refers to the rigidity within German discourse, in which listening has become a rarity and being in the right often seems more important than understanding.

Margherita Moscardini's The Stairway: Is it possible for a Sculpture to become a stateless Space?

For me, a central work of this Biennale is Margherita Moscardini's The Stairway, a sculptural installation at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art. A stairway you can climb up and down. The stairway, which acts as a bridge between the exhibition spaces at KW, consists of 572 numbered stones. Each stone is a unique sculpture, connected and fixed to the others by interlocking joints. Each stone was once “transferred” and has now been given back for the exhibition as a “masterless” alien body within the legal system – accessible, connected, functional: Margherita Moscardini has used a systemic trick by bequeathing the stones to stateless or transnational places and institutions beyond national affiliations, to organisations without national borders, autonomous regions, and groups, which were then asked to return them. The numbers on the stones correspond to their certificates of authenticity and deeds of assignment. Now the stones belong to no one. And this staircase is much more than a sculpture; it is a space of thought that refuses to belong to a particular territory. It is a blueprint for belonging without ownership, for connections without sovereigns. Every step you take on it makes you realise how shaky our constructions of property, state, and territory are. (The slightly shortened treads of the steps demand that you really walk carefully.) This conceptual thought experiment raises the question: Is it possible for a sculpture to be a space that distances itself from the sovereignty of the state whose territory it physically occupies?[1] The underlying context of Moscardini's work refers to a historical structure of power: the so-called status quo of religious places in the Holy Land. But her work does not take a stance – it evokes a feeling. A feeling that every set of rules is a fragile one.

That art can be a place to which neither land nor ideology belongs. A space in between. A utopian offering, highly inspiring with regard to the real-political questions that today are more urgent than ever.

Further Positions supported by a distant Practice – and yet with a current Impact

My attention on the KW tour is drawn to a pufferfish-like creature with a trunk (fig. 1): Anawana Haloba's sound sculpture Looking for Mukamusaba – An Experimental Opera, it is revealed upon further reading, is an experimental opera that explores the oral storytelling traditions of southern Africa. It is about remembrance, resistance, and community. Historical female figures appear in it and unfold their stories in a sculptural space resonating between masquerade, myth, and political song.

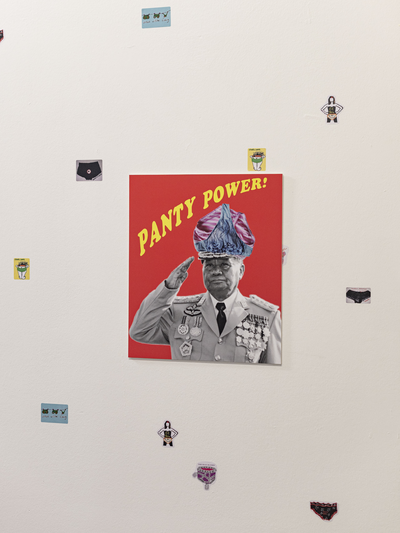

The Panty Power Attack is a significantly less encoded protest action with underwear by Panties for Peace: in 2007, female artists from Myanmar sent panties to the military junta – a provocation of the local superstition that female pants could invalidate male power. Hardly ever has the intimate been so political and so – hopefully literally – disarmingly absurd.

Other than that, there are hardly any explanations in the scenography. Even without these, supposedly humorous works, such as Htein Lin's performance The Fly (2008) or Chaw Ei Thein's video work Scorched Fly (2022), leave me personally rather breathless. Far more subtle, however: Nge Nom's work relies on radical simplicity – it confronts in an immediate way. The Ditch is an excavated trench [KW]. A minimalistic gesture that resonates deeply once you know the background: after the military coup in Myanmar in 2021, Nge Nom founded a movement (CDM) that offers non-violent resistance and supports strikers. Her identity remains hidden for security reasons. In her installation, she recalls a personal escape experience: after a protest action, she hid in a ditch while friends were arrested. The work centres on trauma, survival, and the silent solidarity that exists between generations.

A banner for the Big Mouth Comedy Club of Bosnian artist Mila Panić is visible in the courtyard of KW – the entrance leads us through a “throat” into the basement of the institution, where she performs on six evenings with other comedians (including on 31 July 2025[2]). Panić uses sharp humour to address the invisibility of migrants and war refugees. Her stand-up program performs as a courageous voice against indifference, marginalisation, and media power. Big Mouth does not only refer to satire but also to the risk of opening one's mouth – and being heard without being locked away.

Another exhibition venue is the Sophiensæle. Not only do the so-called focus tours, offered in all of the venues, take place here, but also programs such as Hä?, a production by Simone Dede Ayivi & Kompliz*innen about mutual understanding in times of a shift to the right – about the struggle for diversity, belonging, and the “We” that everyone talks about.[3]

Indian artist Amol K Patil links the history of Berlin's Sophiensæle with the BDD Chawls (Bombay Development Departments) in Mumbai – densely populated housing estates of the labour movement, places of political rebellion and communal life. In BURNING SPEECHES, he uses sound, movement, and remembrance to create a visual echo of this history: speeches, songs, drawings, and a radio going up in smoke unite Ambedkar, who played a central role in drafting India's constitution, Rosa Luxemburg, and the labour movement as part of a poetic theatre of resistance.

His focus on how endangered public free speech is in repressive contexts is also a reminder of the need to fight for alternative (oppositional) voices. These are the works and themes that resonate with me.

Who is it?

Before the impression is created that the exhibiting artists are from a completely different world far removed from the established art market, it should be noted that Amol K Patil[4], Margherita Moscardini[5], Banu Cennetoğlu[6], and Lothar Hempel[7], for example, all clearly have Western gallery representations. Pélagie Gbaguidi[8] also has an institutional presence. From the former GDR, a work by the artist group EXTERRA XX, founded in Erfurt in 1984, will be shown at KW, as well as a documentary in Lehrter Straße, and among its members[9], Gabriele Stötzer[10] in particular is celebrating international success.

So what to do with it?

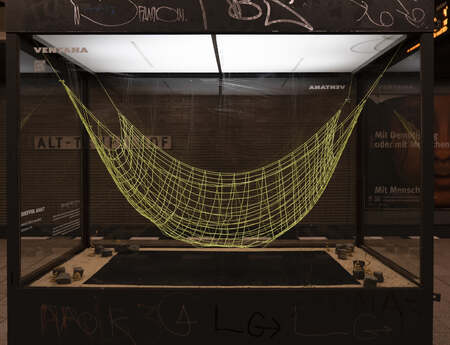

The works on display at this Biennale provide insights and pose challenges: between sculptures, installations, textile art, painting, photography, video, performative readings, encounters with artists in public spaces, discussion forums, and even tribunals, the numerous artists[11] from 40 countries create a delicately interwoven and potentially sustainable net(work) – a space for thought in solidarity on the question of what humanity might actually mean if it had to be re-envisioned beyond repressive frameworks of the state. This affects us just as much, not only because of the causal correlations between the faraway countries and our own history and form of society, but also because we find ourselves in a phase of upheaval. We have to acknowledge that everything is interrelated and that relations determine cause and effect. That many are fundamentally struggling to cope with this has been obvious for some time. Christina Zück's reflection on the “ozeanische Gefühl der Erschöpfung” (oceanic feeling of exhaustion) as a symptom of the late capitalist present comes into my mind like an echo[12]; and we haven't even touched on the pandemic or the recent wars yet: In the capitalist world, the ideal of the self has developed into a key social motivator. Self-optimisation, individuality, and uniqueness are destabilising social relationships. The permanent state of competition creates mental pressure: success provides the sole possibility of short-term escape from an endless wheel of achievement. Depression and a state of chronic fatigue are symptomatic of this development, the result of a heightened self-awareness, sensitisation, and the exploitation of the self within the neoliberal system.

The 13th Berlin Biennale is displaying art that deals with repression, torture, expulsion, and exile in a place where society is basically – also – completely exhausted. Seems not to work well together, but is this perhaps a moment worth embracing? Given the works, their contexts, and the positions of the artists, exhaustion, anxiety, and feelings of helplessness might not be perceived as weakness, but by taking a moment to breathe, they may instead lead to the beginning of a renewed way of dealing with the world.

The Swiss curator Roland Scotti recently wrote in view of the wars in Gaza, Ukraine, and Sudan: “If the only hope being nurtured is the hope that we will become more prosperous on the soil of mass graves, then humanity has probably disappeared.“[13]

We have enriched ourselves with a wealth of inner experience during our exhibition tour and are now left with some rather daunting questions, which, given the intensity of what we have experienced and the urgency of so much real-political inhumanity, we will on the one hand have to leave alone for the time being. On the other hand, many of the rigorous, (still) untamed or unadapted works show just that: humanness. Without appearing hypocritical. Being human is made easy to experience here – by listening, by observing, by interacting with art, and by discussing it.

The 13th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art was curated by Zasha Colah (born in Mumbai, India, lives in Italy) and Valentina Viviani (born in Argentina, lives in Italy) acting as assistant curator. Exhibition venues are: KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Sophiensæle, Hamburger Bahnhof - Nationalgalerie der Gegenwart and a former courthouse in Lehrter Straße in Berlin-Moabit. The Berlin Biennale is organised by KUNST-WERKE BERLIN e. V.; since 2004, the BB has been supported by the German Federal Cultural Foundation as one of its cultural beacons in Germany.

Duration of the exhibition:

14 June – 14 September 2025

Webpage: https://13.berlinbiennale.de

This article was originally written by Jana Noritsch in German.

[1] This is an original question from the pen of Alicja Schindler:

https://13.berlinbiennale.de/en/artists/margherita-moscardini

[2] See https://13.berlinbiennale.de/de/programm/kalender

[3] Barbara Hoppe on the creation of the multimedia performance by Simone Dede Ayivi (director of the play ‘Autsch - warum geht es mir dreckig’) and her accomplices

: https://feuilletonscout.com/theaterpremiere-hae-fragen-nach-dem-wir/

[4] Hayward Gallery London, Museum De Pont Tilburg, SITE Santa Fe, BAMPFA Berkeley, TKG+ Projects, Shrine Empire Gallery, Upstream Gallery Amsterdam

[5] Ex Elettrofonica Rome, MAXXI in Rome, Ar/Ge Kunst in Bolzano, and others

[6] Rodeo Gallery (London + Piraeus)

[7] Art (Paris), Gerhardsen Gerner (Berlin/Oslo), Anton Kern Gallery (New York), and others

[8] Institutional Collections: Illinois Holocaust Museum, Kanal–Centre Pompidou

[9] Monika Andres, Gabriele Göbel, Ina Heiner, Angelika Hummel, Birgit Quehl, Claudia Bogenhardt, Tely Büchner, Monique Förster, Harriet Wollert, Gabriele Stötzer, Verena Kyselka

[10] Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst Leipzig (GfZK), NGBK Berlin (Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst), Albertinum Dresden, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für Moderne Kunst (BLMK), EIGENHEIM Berlin, Galerie LOOk, Wendemuseum Los Angeles (USA)

[11] Link to the list of all artists in the exhibition: https://13.berlinbiennale.de/en/artists/list Please note that the artists' names are sorted alphabetically by first name, not by surname as is the Western standard.

[12] Christina Zück: “Onkomoderne - Das ozeanische Gefühl der Erschöpfung”, (Onkomoderne - The Oceanic Feeling of Exhaustion), from one hundred 2023: https://www.vonhundert.de/2023-02/982_zueck.php

[13] Roland Scotti, 2025, Text for Selim Abdullah (publication is planned: “Selim, For Palestine.” In: Selim, For Palestine, Milan)