Statue Rubbing: The Ritual of Touch

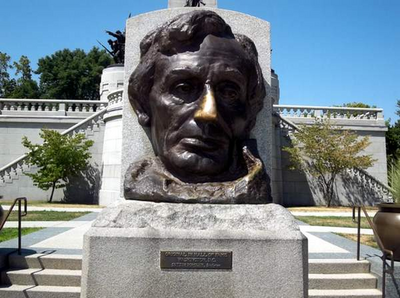

Have you ever touched the nose of Abraham Lincoln in Springfield, Illinois, for good luck or rubbed St. Peter’s feet in the Vatican? You are not alone! Let us explore why we feel the need to touch some statues more than others – and whether they are, in fact, lucky.

Many cities all over the world, from Paris to New York, have it: that one bronze sculpture with one of its more prominent features standing out because of its distinct golden glow, polished by the touch of hundreds of thousands of hands. More often than not in a somewhat inappropriate place. Rubbing public bronze sculptures has become a ritual amongst tourists and locals, so much so that the act received its own terminology and its own Wikipedia page: Statue Rubbing.

Most statues promise some sort of positive result in return for this act: touching the breasts of the Juliet statue in Verona is supposed to help with romantic endeavours, despite the demise of Shakespeare’s tragic heroine Juliet, who it was modelled after; rubbing the crotch of the Victor Noir statue lying on the journalist’s grave in Paris’ famous Père Lachaise cemetery is said to prevent infertility; and grabbing the testicles of the bronze bull of New York’s Wall Street might bring good luck to some hopeful investors. Some statues are even surrounded by legends explaining the reasons for this particular positive effect. For example, the small lion heads in front of the Munich Residence with their shiny noses are said to have been touched by a lucky poet who had written a less than flattering poem about the king. When the king, instead of beheading the poet, let him go and even rewarded him handsomely because he was so impressed by his skilled wordplay, the lucky guy was so relieved that, upon leaving the Residence, he had to lean on the lions in front of the building for support. Some of his incredible luck might rub off on passersby when touching those very noses, or so it is believed.

Are we just superstitious?

Most of the statues named above promise good luck to whoever touches them. The act of touching becomes a means to connect with, and not only connect, but actually receive something from a piece of art. Something a little more tangible than the awe and inspiration we might feel when looking at it. When following the ritual, we hope for a bit of good luck in our lives, manifesting itself in concrete rewards such as winning the lottery or the long-anticipated invitation to a date by a crush. But who, in our modern day and age, actually believes that a statue has magical properties that can be transferred by touch? Probably not a lot of the people who perform the act. So why do we feel compelled to touch these sculptures?

A lot of the bronze sculptures we see in public spaces depict real humans, some of them historical figures, some mythological or literary heroes. Often life-sized, they walk, sit, or stand among us. Art historian David J. Getsy describes the relationship between statue and viewer as such: “The situation the statue presents is more akin to an encounter with another person than any two-dimensional representation could offer.”[1] However, he elaborates, a statue remains immobile, mute, and essentially lifeless, no matter how skillfully the illusion of movement might be crafted. This passiveness – or, if you will, the performative act of stillness – is what distinguishes a statue from its viewers, humans made from flesh and blood, and it is this distinction viewers want to reinforce when interacting with it, according to Getsy. By touching a statue, in a way, we assure ourselves of our own humanity, of our power over an object that might look like us but cannot surpass us. The statue, however, remains unfazed by this in its “passive resistance”[2], further provoking acts ranging from vandalism to gentle, curious touch to rubbing for good luck.

More than just Fun: Democratising Art

While statue rubbing might seem like little more than a bit of cheeky fun with a statue’s private parts – just look at Molly Malone in Dublin! – or a touristy photo opportunity at first glance, Getsy’s analysis shows that there is more to it. And there might be yet another explanation for why we feel drawn to the shiny bits of public bronze sculptures. The urge to touch a piece of art can rarely be satisfied in other contexts. Most museums and galleries explicitly forbid visitors from touching the exhibits. Some with good reason, for conservation purposes; others because it is what one does. We are used to admiring art from afar. Which does not mean that we would not like to touch it. Some pieces, especially sculptures, with their sheer physical presence, evoke a strong desire to touch them and explore them further with more of our senses than just our vision. But more often than not, touching a sculpture remains the privilege of museum or gallery staff, conservators, and collectors. Historically speaking, touching sculptures could even be seen as an elite privilege, as museologist Fiona Candlin points out.[3] She demonstrates that, in past centuries, exploring exhibits by touch was not uncommon but reserved for the upper class. Today, whoever has the financial means to purchase a piece of art can enjoy the sensation of physical touch, while it remains an unfulfilled desire for most other art lovers.

Public art has the power to cancel out class differences and level the playing field. It is available to everyone, seven days a week, twenty-four hours a day. No alarms, no security guards, nothing keeps curious hands from exploring it. People from all walks of life, no matter their background, can get close to it and experience it with all their senses – well, most of their senses. Luckily, statue licking does not seem to have been invented yet, although kissing certain statues is already practiced as a good luck ritual in some places. What makes bronze sculptures special among the whole corpus of public art is the signal they send. The shiny bits seem to call out to us, not only tolerating physical touch but begging for it. City guides, tour books, or even signs next to these sculptures give us permission to do what is otherwise denied to us. In a way, public sculptures allow for a more democratic process of experiencing art.

All this goes to show: While statue rubbing might not bring good luck per se, it certainly has its positive effects on the community. However, let us not conceal the legitimate concerns around this practice: Some statues have suffered considerable corrosion damage due to all the eager hands. Verona’s Juliet statue, for instance, created in 1969 by sculptor Nereo Costantini, had to be replaced in 2014 by a replica in order to preserve the original. So, let us rub our statues with care and consideration so that they might bring many more generations good luck – or something akin to it.

[1] David J. Getsy (2014): Acts of Stillness: Statues, Performativity, and Passive Resistance. In: Criticism, Vol. 56, No. 1, pp. 1–20.

[2] See above.

[3] See Fiona Candlin (2008): Museums, Modernity and the Class Politics of Touching Objects. In: Touch in Museums. Policy and Practice in Object Handling, ed. Helen J. Chatterjee, London/New York: Routledge, pp. 9–20.

Photos:

Nereo Costantini, Juliet: CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/us/>, via Flickr.

Hubert Gerhard, Bronze Lions: CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Jules Dalou, Tomb of Victor Noir: CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Jeanne Rynhart, Molly Malone: CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Gutzon Borglum, Head of Abraham Lincoln: CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

The article was written by Sophie Fendel in English.