Preserving Ideas: The Challenges of Media Art Conservation

In the traditional fine arts, as painting and sculpturing, the typical job description of a conservator might be summarized as stopping the natural degradation and restoring the appearance of the artwork to the very moment it was created, back to the so-called original version. The conservator would consolidate the material chosen by the artist and would try to reduce the changes made to the original artwork to a minimum.

However, Media Art is a complex arrangement of many objects, materials, and media, such as film, tape, vinyl disk, hardware, etc., constituting the installation, that must be exhibited according to specific instructions. The artist could include the natural degradation of the material as the original characteristic of his piece. Moreover, the very existence of the artwork could rely only on the visitor’s participation. Thus, how to conserve technologies that, due to their nature, are destined to break (planned obsolescence)? How to identify the original when reproduction and change are the main characteristics?

These are only a few of the conservation challenges brought by Media Art, a contemporary artistic practice, that since the 1960s started to become a fertile researching field all over the world.

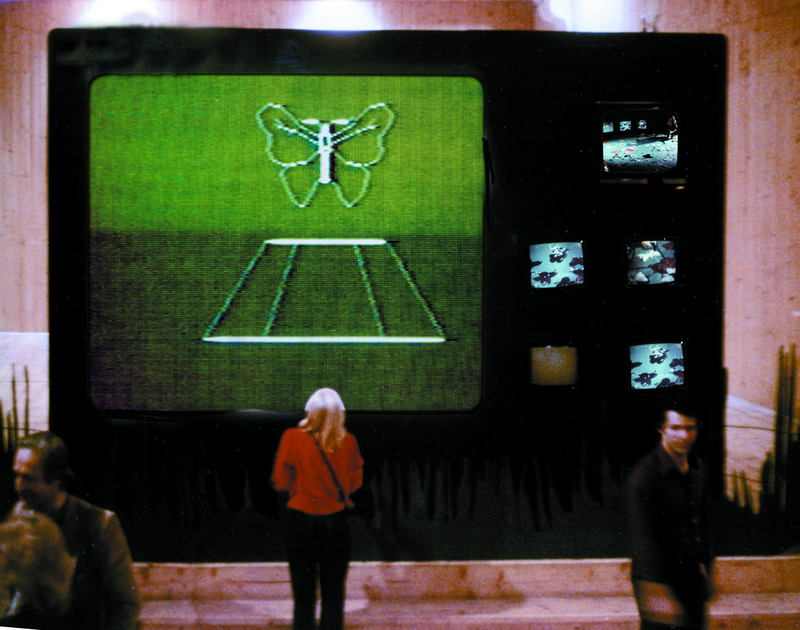

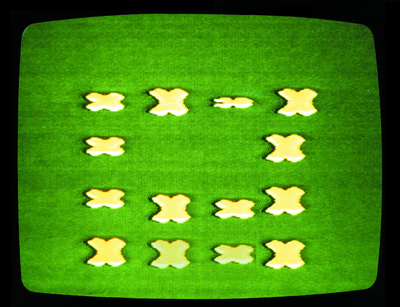

Let us have a closer look with some examples. The video-sculpture Maxi TV made by the Italian artist Federica Marangoni in 1984, is a wooden structure which simulates a huge TV. The large video is a rear-projection of her previous video-artwork Video Game (1983), which was made with computerized methods, very novel in the artistic practice at the time. The "buttons" aside the screen are five real monitors, running her video-performance Il volo impossibile (1982) and video elements used in the performance (multi-channel installation). Thus, which is the original artwork? Video Game, Il volo impossibile or the structure enabling their union? Does the value of each artwork change when it comes to make conservation choices?

It is now crucial to outline another important characteristic of Media Art: it needs to function in order to exist. When Maxi TV is off, it is just a sculpture. A painting conserves its value also when the museum is closed and dark, but the video exists only when the monitor runs in the exhibition space. Thus, the installation exists only when all the components are displayed in relation with each other, the public, and the exhibition space. In Media Art, these characteristics are not only extra features, but they play a fundamental role in the precise definition of the artwork. Do you remember the first StarWars movie? In 1997, it was released for cinema distribution during a special premiere and a huge advertising campaign. It was a big event. Nevertheless, the intrinsic value of the movie has arguably not changed on the TV. On the contrary, if the media artwork loses certain connections, its identity will change completely. Zen for Film (1965) by Nam June Paik (one of the fathers of Media Art) is a 16 mm film, projected in a loop on the exhibition wall. The artwork is based on the natural degradation of the analogue film, constantly running in the projector and collecting scratches and dust over time. The true experience and the real artwork will be only in the exhibition space, matched with the constant mechanical sound of the projector that progressively ruins the film.

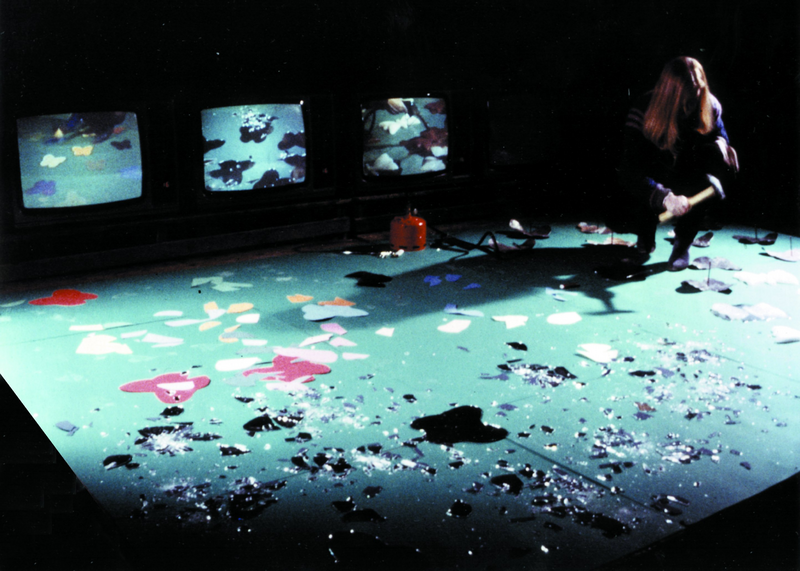

In some other cases, the context and the artwork’s functioning are not enough. People allow the artwork to exist. In the computer-based installation Interactive Plant Growing (1992) by Christa Sommerer and Laurent Mignonneau, the visitor touches live plants displayed in the installation. By producing an interaction with them, the person decides how and when the growth of 3D plants take place in the computer environment, simultaneously shown on a projected screen. Without people's involvement, this work would not function and thus, not exist.

Due to the complex and variable nature of Media Art, it is difficult to outline general conservation practices. Sharing experiences and collaboration have become key. Teamwork between different fields of expertise is essential to have a 360° view of the artwork and outline the best practices for its conservation. Therefore, curators and restorers now work with technicians, computer scientists, engineers, and artists. The same occurs also between institutions: on one hand important players as Documentation and Conservation of the Media Arts Heritage and Matters in Media Art projects, Rhizome, Smithsonian Institute share experiences with open-source tools. On the other hand, big institutions such as Tate Modern, Zentrum für Kunst und Medien, Museum of Modern Art, Small Data, and LIMA, connect smaller organizations and share best practices. This was the goal, when in 1997 over thirty organizations worked together in the first international congress with the provocative title “Modern Art: Who Cares" in Amsterdam, following the creation of “The International Network for the Conservation of Contemporary Art” in 1999, and the second congress "Contemporary art: Who cares" in 2010.

Since then, attention has been focused on new conservation criteria: not only materials, but also intangible aspects, as Pip Laurenson from Tate points out, like the exhibition context, the experience, and the meaning of the artwork. Alessandra Barbuto and Laura Barreca from MAXXI in Rome add "it is no longer a unique piece created by an artist but a process of cultural participation involving the public, the work itself and the museum. The interpretation of the work of art as an idea, and not only as a physical object, is now broadly confirmed in contemporary artistic practices.“ A concept endorsed also by Richard Rinehart, the Director of the Samek Art Museum, who encourages to think of the artwork as a musical score, wherein both cases the content is the core rather than the medium.

The conservation practice then becomes flexible, open to questions, and linked to the production and display context. A debate that nowadays heavily involves the artists. One of them, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, has even created guidelines on how to document artworks step by step during the whole creation process, in order to provide a useful interpretation tool for conservators and museums.

Media artworks are complex pieces including different features that need to be at first understood, documented, and then displayed. The correct documentation of these features is indeed a key step in the conservation process. It will allow the truthful display of the artwork in the future.

In Italy, big institutions such as the Archive of Biennale in Venice, have undertaken the digitization of early audiovisual media, as tape and film, to save and document the information recorded on them. A significative project worth mentioning was the collaboration between the Contemporary Art Gallery in Ferrara and the restoration lab "Camera Ottica" in Gorizia in 2012, which focused on the digitization and the documentation of many video-artworks of the Ferrara-based fonds "Centro Video Arte". This Center (1972-1994) was an important researching hub for artists, such as Fabrizio Plessi, Federica Marangoni, Michele Sambin, Giuseppe Chiari, and internationally relevant including Woody Vasulka, Marina Abramovic and Ulay.

At the National level, the Ministero per la Cultura is promoting some projects in order to raise awareness and to help Italian institutions with the documentation and thus, the conservation of the artworks. First of all, the Ministry is currently updating the Italian regulation Opere/Oggetti d’Arte Contemporanea (OAC) to describe contemporary artworks. Furthermore, the recent ministerial project "VideoArte in Italia" is specifically focused on audiovisual artworks. With the help of an extensive survey, the project aims to document the entire audiovisual heritage of Italy and to create connections between the institutions.

As an example of the increasing awareness, from my direct and recent experience, I would also like to mention the cataloguing project by the institution for contemporary art "Careof" in Milan. In particular, Dott.ssa Lisa Parolo, the supervisor of the project, and I are outlining the structure of a database that can be used to document the audiovisual artworks in the Careof archive, following guidelines from OAC and the Digitizing Contemporary Art project, from Europeana.

In conclusion, in Media Art different maintenance issues can coexist at the concrete and abstract level. Conservation is at first a documentation and a research that involves various experts with nontraditional background and the artist. Decisions must be balanced between the technology obsolescence, the institution’s possibilities, and the creator’s will. The meaning of the artwork as described before by Laurenson, is the main concern, allowing mutations and replacements when needed.

Furthermore, artworks based on virtual reality technologies, as Memory Theatre (1997) by Agnes Hegedüs, are arousing the most recent interest of the Tate Modern and ZKM. Their main concern is how close to emulate the early approaches to VR from the 1990s and how to exhibit them in a time where the technology enabling VR has completely changed. Should the interface by which the visitor interacts with the artwork, change with the modern visitor himself?

In the world of Media Art many new challenges lie ahead. Stay tuned!

Author: Vittoria Gelati

Vittoria Gelati is an Italian Ph.D. student in Art Conservation at ABK Stuttgart. Her research focuses on documentation and conservation strategies for complex Time-Based Media artworks. She currently collaborates with Ministero della Cultura for the project “VideoARte in ItaliA”, the association for contemporary art Careof in Milan, and the museum ZKM | Zentrum für Kunst und Medien in Karlsruhe.

Supervisor: Dott.ssa Lisa Parolo

Lisa Parolo is Ph.D. in Art and Audiovisual Studies. After three years as Post-Doctoral Research Fellow at the university of Udine she is now a freelancer advisor for many contemporary art collections on preservation, digitization, exhibition and archiving practices. She has edited different books and she has written many essays on Italian video art and experimental film.

Published: July 2021