Fall of the Idols

As a child, Enrique Marty (1969, Salamanca, ES), was surrounded by the religious imagery in Catholic churches. The realism of his gesturing painted figures is informed by the Spanish Baroque. But Marty is not a believer.

On the contrary. "Fall of the Idols", which is on show in MUSAC in León, Spain, questions human behaviour, such as fanatacism and idolatry.

In the 16th century, philosopher Giulio Camillo conceived a Theater for Memory, a structure shaped liked a Roman amphitheater with a seven-tiered edifice filled with paintings of mythological figures as well as hundreds of rows of drawers filled with cards which contained all kinds of knowledge. The spectator in this theater stood in the center of the stage, and by meditating on any emblematic image, allowed him to "be able to discourse on any subject no less fluently than Cicero".1

Rage and humour

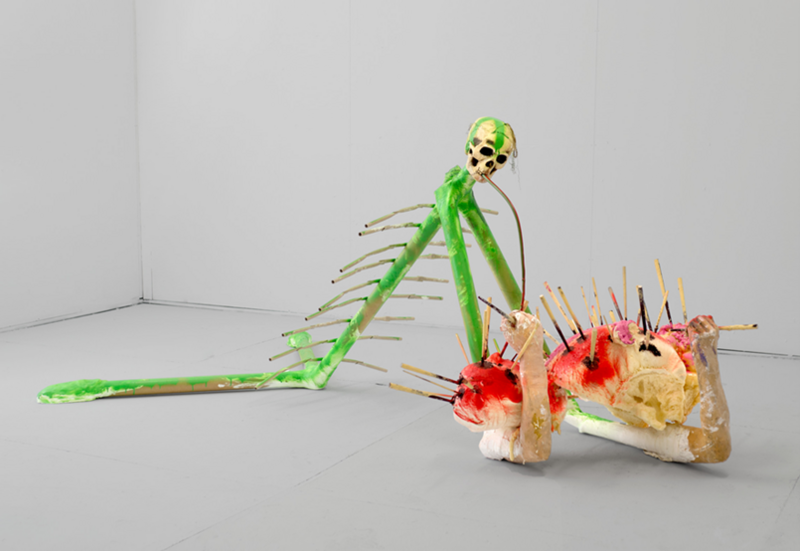

At the recently opened group exhibition The Sleep of Reason at MUSAC in León, Spanish artist Enrique Marty recalls Camillo’s theater in his work Fall of the Idols. This installation from the MUSAC Collection is composed of over 300 sculptures that the artist, together with some collaborators, created between 2011 and 2015, based on photographic documentation of sacred images taken by the artist in churches, temples, museums and public monuments all around the world.

Using “leftovers” from the artist’s studio, Marty and his collaborators—most of whom were people from outside the artistic field—created new idols with absolute freedom of representation, in which the poor nature of the materials used and their unskillful craftsmanship were evident. The result is a group of resignified icon-idols, endowed with both rage and humor.

Taking on a different presentation each time it is exhibited, the installation at MUSAC is a reimagined version of the Theater for Memory. An organized chaos of furniture, exhibition elements and props form tiers on opposing walls of the space where the sculptures, lifted onto pedestals in an attempt to reach as high above, are accumulated. In the center, a spiral staircase goes up to the ceiling, from which several other sculptures climb down in their own silent procession. The spectator passes through as if in the central nave of a church, with the statues of saints looking down in keen observation on their subject, the observer, observed:

The most ancient and wisest of writers have always been accustomed to recommending to their writings the secrets of God under obscure veils, so that they be not intended, unless by those who have ears to hear…

When he was a child, Marty created a sort of altar with an idol in his living room. He closed the room with a padlock and hid the key:

"I was fascinated with the idea of that kind of God which was there, in that locked room, and which no one could see. I was wondering, if nobody looks at it, does it still exist? The audience of all this were only my parents, it was made for them, to see their reaction. Today, I am still doing the same thing but widening the spectrum."2

Dark side of human behavior

Fall of the Idols is a representation of Marty’s personal universe, which shows a clear fascination with the ugly, the sinister or the absurd. It is a universe that assimilates the tradition of art history and philosophy, using it to examine the evils of Western society and the dark side of human behavior. With influences from classical art, Baroque sculptures, anthropological objects, horror movies, contemporary fantasy literature, and almost anything derived from non-canonical representation, Marty creates a giant stage set in which the sculptures are actors in the play itself and the spectator becomes an involuntary accomplice.

It is impossible not to look at the idols in the MUSAC installation. In fact, it is hard to focus on just one sculpture, as there are many “drawers” to open in this theater, drawers that unlock questions that don’t give answers but that lead to more questions.

Just like a huge cabinet of curiosities, the artist’s “specimens” are decontextualized idols, objects that in one way or another have been venerated, not necessarily on a religious basis, but on a spiritual, political or ideological one. These idols carry meanings to each of their creators—personal amulets or totems—that combined together possess a spiritual force akin to any theocratic one, emphasized by the angry shadows that they cast and adding to their theatrical effect. But the shadows are more than just an effect, they allude to the entirety of the unconscious, the unknown dark side that is rejected and repressed, in Jungian terms.

Ideologies become idols

Ideologies are modern idolatries. Like Nietzsche’s Twilight of the Idols, Marty’s work examines what we worship and why—idols that, according to the German philosopher, must be “struck with a hammer as with a tuning fork”3 —from the obvious religious images, to the cargo cults that surged in the island of Vanuatu after World War II, to modern-day cults, whose worshippers are all trapped within a mindset of primitive belief systems, incapable of questioning the higher truth just as the early Church favored the “poor in spirit” over the “intelligent”. But when ideologies become idols, the noble purposes behind them are lost.

And that is what Marty tries to portray in his installation. The mere presence of these idols in a cultural temple announces their downfall. It voids them of any ideological meaning and though they stand high atop pedestals as if in their own chapels, they are somehow ridiculed, converted into tragicomic objects that suggest the collapse and futility of philosophies and great ideals.

The very materials from which they are made, far from the exquisite ones used throughout the history of art, already show a critical and formal resistance to the dominant social and cultural ideologies of our time. “Ultimately, the world is a tragicomedy”,4 and the theater is “a vision of the world and of the nature of things seen from a height, from the stars themselves and even from the supercelestial founts of wisdom beyond them”.5

MUSAC, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León, is located in the North

of Spain. Musac.es

Enrique Marty enriquemarty.com

www.enriquemarty.com/WORKS._Fall_of_the_Idols_%282015_2011%29.html

Interview (in Spanish) https://youtu.be/PagyWXROFtA

Author: Kristine Guzmán is a curator and general coordinator at MUSAC, León (ES). Trained as an architect, her interest lies in contemporary artworks that address space and practices that are on the border of art and architecture.

Cover picture: Enrique Marty Fall of the Idols. Photo G. Villamil. El Norte de Castilla

1. Yates, F.A. (1966) The Art of Memory. The University of Chicago Press (p.130).

2. Marty, E. (2017). Alberto Martin I Enrique Marty Una conversación. Observer, observed. Nocapaper Books & More/La Gran. 61.

3. Nietzche, F. (1911). The Twilight of the Idols. T.N Foulis. (p. xviii).

4. (Marty, 2017)

5. (Yates, 1966)

Article published on April 30, 2021