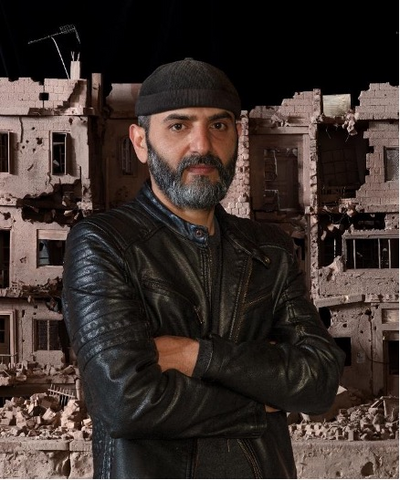

Khaled Dawwa / Voici mon cœur ! A contemporary War Memorial

As part of the commemoration of 80 years of freedom in the Netherlands, the Museum Beelden aan Zee is currently presenting an impressive installation by Syrian sculptor Khaled Dawwa (Maysaf, 1985). The six-metre-long war memorial, entitled Voici mon cœur ! (Here is my Heart!), takes the form of a ruined façade in Damascus.

What does it mean to leave your home and move to Europe?

While some months ago we commemorated the liberation from German occupation in the Netherlands – now 80 years ago – this devastating installation by Khaled Dawwa appears at Museum Beelden aan Zee. Dawwa's work offers an extremely topical perspective on freedom. Especially now, with all the global threats playing out in Europe and elsewhere in the world, you get the impression that only some parts of Europe are still safe (for the time being). No wonder refugees, including Dawwa, ultimately choose to come to Western Europe.

Scale model

Dawwa's installation resembles a scale model, crafted with precision in clay and various other materials. The long row of destroyed buildings, displayed in a separate darkened room, makes you aware of the fact that our freedom is fragile. It’s a summer night in Syria, and Dawwa shows the installation with a blue night light. As a visitor, you can get a small torch, which you use to walk along the scale model. The moment your light shines, you can see how extensive the material damage to the buildings is: floors have collapsed, windows are missing, and concrete reinforcements stick out into the air. It reminds you of well-known news images of wars in Syria and Gaza, and of course the war in Ukraine. Dawwa deliberately chose not to depict bodies; far too shocking for him and the public. He focused mainly on details of utensils, objects and architectural components. In front of the houses are huge piles of rubble where you can see parts of old swings and broken bicycles in between. There are also a few ruined cars lying under the rubble. Further on, there is a half-destroyed dome of a mosque, through which a rocket has flown. Scattered around are destroyed fences. Inside one of the houses, there is a stray football table, and in another house, there are some books left on a table. These are narrative details that indicate that people lived here. The lack of bodies makes it somewhat unrealistic. The reduced size of the buildings and interiors also contributes to a sense of unreality. After all, the reality is a thousand times more intense and incomprehensible. Therefore, people seem unable to take in reports of war and violence through newspapers, television, film or the internet too often (visual images have the greatest impact). It has been found that continuous exposure to images of war and/or violence causes people to shut themselves off as a form of self-protection. The news is too emotional, too poignant and even threatening. These psychological consequences present a wonderful task for the arts, according to the late Dutch opera director Pierre Audi: “The world on stage brings contemporary issues closer than the news itself. Because in the theatre we dream, and it is precisely in that non-reality that we can form a deep connection with what we see. At a time when war and suffering are openly advertised, opera offers hope.” And as far as I am concerned, this certainly also applies to other forms of art like literature, visual arts, film and poetry. These art forms can make the intense issues of war and violence tangible; empathy and compassion arise when we watch the victims. We start hoping that the conflicts will eventually come to an end. In this way, the arts are placed, as it were, between the all-too-realistic images of war and us as viewers; they act as a vehicle for comprehension and empathy.

How can we improve people's lives through art and portray history in a different way?

Arab Politics

In a conversation with Dick Broekhuizen, Head of Collections at Museum Beelden aan Zee (available on the museum's YouTube channel), Dawwa explains that he began to see himself as a sculptor at the time of the Syrian revolution: “I started depicting the events in Syria in clay, which helped me to process what was happening at that time in the country where I was living. I have been interested in the politics of my country and that of the Arab countries in general for quite some time. I wondered, ‘How can we improve people's lives through art and portray history in a different way?’” He found the answer in sculpture. Initially, he worked with the theme of prisons and depicted human figures completely bound in ropes (he himself had also been in prison). With this work, he wanted to tell the stories of the prisoners in Damascus, where hundreds of thousands were tortured and died. Only then did the idea for Voici mon cœur ! come to him; it took three years to complete this immense installation. Eventually it was purchased by a museum in Marseille.

While creating it, he asked himself, “What does it mean to leave your home and move to Europe? How can I best depict the environment of the families I know that lived in a particular house in Damascus?” He tried to imagine their lives based on photographs and thus arrived at this detailed work.

Contemporary War Memorial

The accompanying museum text to the installation states that Dawwa's work can be considered a contemporary war memorial. Admittedly, the rather abstract miniature forms of the work differ greatly from the predominantly figurative representations we know from famous war memorials. In my opinion, that’s not a real problem, on the contrary, it’s an advantage of this installation. The work leaves more than enough room for individual associations with contemporary wars and severe destructions. The artwork touches on universal themes such as the loss of loved ones, the search for a new identity and the quest for freedom. (A quest that for many has resulted in permanent residence in Europe.) Anthropologist Anna Tsing also talks about the ability of the arts to convey passionate connections. In her essay Arts of Inclusion, or How to Love a Mushroom, she calls this “arts of noticing”. Although her argument mainly concerns how we treat the earth, it applies equally to how we treat each other as humans. In my opinion, the arts are capable of depicting difficult subjects in such a way that we do not shy away from them. In other words, we are emotionally moved by sculptures that provide us some literal associations to the violence and destruction of war. As we look back on our own situation and experiences, the process of healing and comforting can start. The viewer develops compassion and empathy; public opinion can shift. The artwork reminds us that the struggle for freedom and human dignity does not end on a specific date but is an ongoing process.

Khaled Dawwa / Voici mon cœur !

4 April - 2 November 2025

www.beeldenaanzee.nl/nl/khaled-dawwa

This article was written by Etienne Boileau in English.