An Emotional Visit to a Dystopian Wasteland

Looking at art is an experience between emotional and cognitive understanding. But what if we were to switch off the rational part of our mind and let ourselves be guided entirely by emotion? Sophie Fendel has done the experiment. A walk through Shu Lea Cheang’s exhibition KI$$ KI$$ at Haus der Kunst, Munich.

Walking up to Haus der Kunst in Munich, Germany, is always a somewhat intimidating experience: the neoclassical colossus with its uninviting, oppressive portico makes you feel small and insignificant. Probably just as intended by the building’s architect in the 1930s. Once a Nazi prestige project, the museum has a lot of history to unpack. And it does, by giving this once exclusionary space back to artists from all over the world. Artists whose work would, in this dark chapter of German history, have been described as “degenerate (entartet)”.

I try not to dwell on this feeling of unease and enter the building. Now I am on familiar ground, in an art space full of light. I buy a ticket to the exhibition KI$$ KI$$ (pronounced: Kiss Kiss Kill Kill) by Taiwanese-American digital artist and filmmaker Shu Lea Cheang. I am not exactly sure what to expect, but I am already intrigued before even setting foot into the exhibition space by the cryptic warning sign at the entrance reading, “Trip hazard: In room 1, robots drive on the floor. Please do not touch them,” and “The mushrooms in room 3 are not hazardous.” What on earth am I in for? I can only assume something hallucinogenic has to be going on in room 3. But this is going to be the last sign I read today, I vow to myself. Because today I am here for an experiment. I have challenged myself not to read up on the exhibition in advance and to turn off the analytical mode in my brain while exploring Cheang’s work. Instead, I want to be guided entirely by my emotions. That means no info texts, no reading up online. I will have to remind myself of this over and over again while walking through the exhibition, since I am usually one of those persons guilty of reading signs and explanations before looking properly at what is in front of me. But not today! Today I am a creature of emotion.

Walking up to the Underworld

I enter a hallway with dimmed lights and a long flight of stairs leading upwards. A neon sign spreads its red glow through the gloomy atmosphere, alternately flashing the words “Kiss Kiss” and “Kill Kill”. It feels somewhat dystopian, this lonely red sign in the high staircase, broadcasting its message somewhere between eroticism and carnage. As if I am about to enter the underbelly of some futuristic metropolis. Shu Lea Cheang (born in 1954 in Tainan, Taiwan) is known for her artistic exploration of technology and digital spaces. Accordingly, the first impression of KI$$ KI$$ screams science fiction. I am hooked.

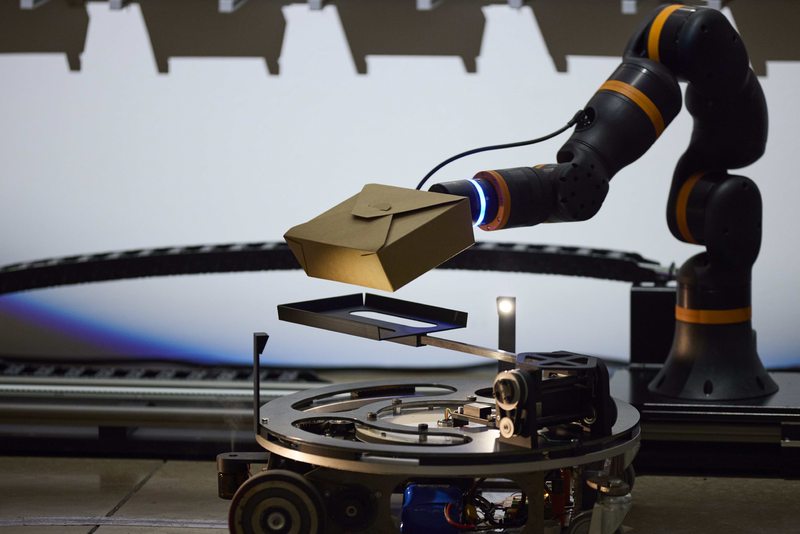

I make my way up the stairs, anxious about what the advertised robots have in store for me. Laser beams? But nothing could have prepared me for the room I entered next. I cannot describe it any other way: Cheang has built a post-apocalyptic robot city devoid of human life. Depressing and fascinating at the same time. In the huge room before me, small robots cruise around laboriously between mountains of trash. Heaps of take-away containers cover the floor. It is a world of high-tech and waste, a landfill run by a tiny, imperturbable robot workforce.

After the initial surprise, I take a step closer, curious what these mechanical workers do except dare exhibition visitors to trip over them. Seconds before one of the robots actually demonstrates its purpose, I understand: They “deliver” the cardboard boxes to the trash heaps by shooting them from a sort of catapult on their back. Suddenly, the dystopian atmosphere of the room vanishes behind the childlike glee I feel when watching the robot fulfil its task. Is there anyone who is not fascinated by observing an intricate machine at work all by itself? I follow the robot around the room to the loading station. A robot arm takes cardboard containers from one of three shelves labelled “veg”, “meat”, and “fish”. There is a choice for everyone, I suppose, but each box is delivered directly to the dump. Immediately, a damper is put on my joy about the little robot. It diligently does its job, but for whom? There is no consumer at the end of its route, no human to feast on the meal it has just delivered, only the landfill. Suddenly I feel something like pity for the busy little robot. Its whole existence seems pointless.

When exiting the room, walking past a table set with animal skulls, which does not touch me in the same way the rest of the room does, I glance at the description sign for this installation: It is called Home Delivery. How fitting.

The Future was Yesterday

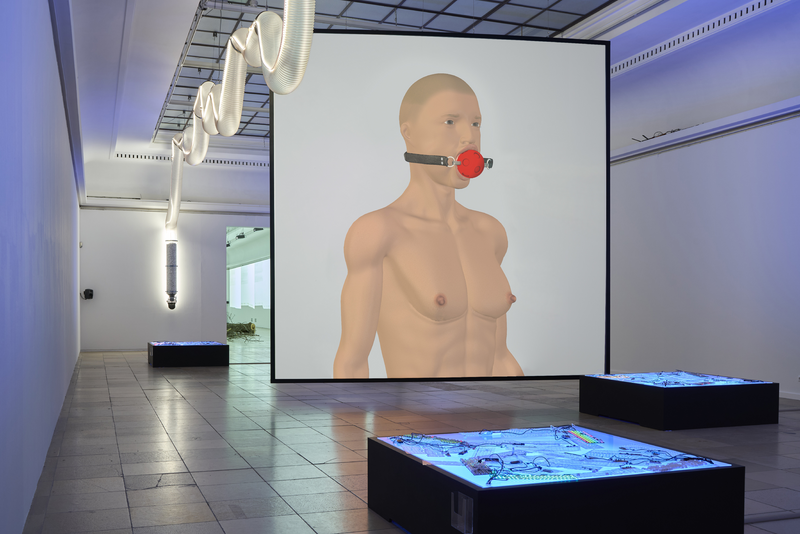

The second room does not look any less futuristic than the first. I am greeted by tables full of what look like discarded computer keyboards, tinged in a blue glow, and a massive screen showing a constantly changing human figure. Of course, my eyes are drawn to the screen (hello, I am almost a digital native!). The figure’s shape oscillates between male and female, between child and adult. At one time, it is a baby with a pacifier in its mouth; at another time, it is a big-breasted woman, the pacifier replaced by a gag. I feel a tinge of shame and avert my eyes. It almost feels as if I were witnessing something too intimate, something not meant for my eyes – but broadcast in 4K on a massive screen.

As the trained museum visitor that I am, I stroll politely past the keyboards, keeping my distance and nodding approvingly while having no idea what they are supposed to tell me in the context of what is going on on the screen. It takes a friendly museum attendant (who clearly does not do this for the first time) explaining to me that I am allowed to press the keys. Obviously, this would have been made clear by the info signs. My resolve not to read them in order to be guided by my emotions backfired there. Oh well! Bravely, we (that is, myself and the very few other visitors who found their way into a museum on this very hot summer day) follow the instruction. Each key spurts out a different word, most of them inappropriate and/or sexual in some way, and soon we are engulfed in a cascade of profanities, which I do not dare reproduce in writing. It makes me strangely giggly to hear so much swearing in the usually so dignified museum space. Chuckling, I walk past the screen and the keyboards towards the next room – and stop dead in my tracks.

Composting Humanity

The third and last room is dominated by a car wreck. Tree trunks and branches have fallen on the vehicle, which is damaged beyond repair; that much I can see even without having the faintest clue about the functionality of an engine. My first impression is that of a terrible car accident, and my thoughts immediately rush to the passengers, who cannot, under any circumstances, have survived such a violent crash. There is a somewhat eerie mixture of whispering and white noise to be heard in the background, adding to the disconcerting atmosphere. Only after this initial moment of shock do I register the screens covering the room’s walls. Rows upon rows of data, seemingly random names and dates, and pieces of information that do not make any sense to me. I am confused: What connects the visceral scene in the middle of the room, this violent clash between nature and technology – with nature as the obvious victor – to this literal wall of text?

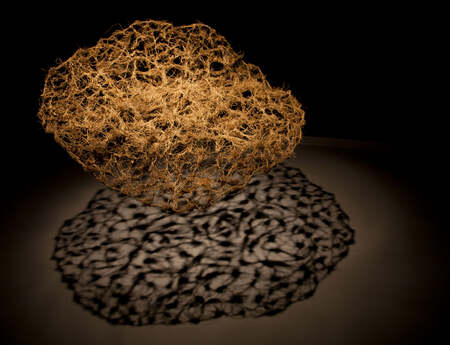

I cave and take a peek at the info sign. This room does not open itself to me quite so intuitively. Before I can read the text, however, another friendly museum attendant joins me and offers an explanation. It is only then that I see the mushrooms. They grow on the dead wood surrounding the car wreck, circuit boards sticking out of them in a weird symbiosis of technology and biology. The initial pang of disappointment (I actually expected something otherworldly after the warning sign outside) quickly disappears when the attendant explains that the radios producing the eerie sound cloud in the room are actually supposed to run on the mushroom’s mycelium. Unfortunately, it does not work reliably with the climate conditions in this room, so the sounds had to be pre-recorded. But the dead wood and the mushrooms are not the only things composting in this room: what I see on the screens all around is data trash, old e-mails, and newsletters nobody reads anymore. Looking more closely, I recognise the small animation at the bottom of the screens, showing soil from which small plants are growing. The entire room suddenly becomes a giant compost pile.

Lost in thought, I slowly walk outside, leaving Cheang’s dystopian wasteland behind me. I am content with my experiment: With the exception of the third room, which revealed its meaning only intellectually, all the installations in KI$$ KI$$ spoke to me on an emotional level. I gave them meaning by experiencing them – even though that meaning may differ from what the artist intended. In this, our age, the Information Age, we are used to approaching things rationally: we gather information and data and contextualise the results with what we see. It is a sensible approach in many aspects. But the inherently emotional component of art might get lost on the way when we think too much before taking it in. So, the next time you walk into an exhibition, maybe read the info signs last. Or not at all. Who knows what you might feel?

The exhibition KI$$ KI$$ by Shu Lea Cheang is still running until August 3, 2025, at Haus der Kunst, Munich.

This article was written by Sophie Fendel in English.