Moving Female Sculptures – Performative Lectures on Berlin Female Sculptors of Modernism

Birgit Szepanski's performance project Moving Female Sculptures commemorates forgotten female sculptors in Berlin in the 1920s who helped influence the city's art scene.

Moving Female Sculptures is an urban art project that makes women sculptors of the so-called 'first generation' visible in the places where they lived and worked in Berlin, such as Emy Roeder, Renée Sintenis, Louise Stomps, Jenny Wiegmann-Mucchi, Christa Winsloe, Tina Haim-Wentscher, and Sophie Wolff. Artist and art historian Birgit Szepanski presented a series of four performative lectures in autumn 2023 featuring sculptures by women from the 1920s, rarely exhibited and sometimes forgotten to this day, and linked them to public spaces in Berlin. The project is a tribute to the female sculptors; it is a feminist statement and an urban utopia: for what might the city look like if these first modern female sculptors had been able to realise large-scale sculptures? How would female artists perceive and experience the city today if there existed more sculptures made by sculptresses and we could look back on a feminist sculpture tradition? Might this have created a female city in the city?

In Berlin as well as in other European capitals, only a few sculptures by female sculptors are to be found in urban spaces. On the contrary, classical monumental sculptures dominate prominent city sites. Many of the artistic ideas and visions of female artists were not realised, and their stories were thus not told or retold. Birgit Szepanski explored these art historical and urban voids and found with Moving Female Sculpture a discursive and poetic way of making them visible.

In her performative lectures, Birgit Szepanski recounted the difficult journeys of the women sculptors and made connections between places, individual works, and the biographical challenges faced by these modernist sculptresses. Fascinating synergies were the result. Szepanski, for instance, re-enacted the famous sculpture Daphne (1918) by Renée Sintenis (1888-1965) on the lawn of Steinplatz, opposite the University of the Arts. Under a birch tree, Birgit moved her arms over her head in slow, searching movements and placed her hands on top of each other in a slight twist. She closed her eyes while doing so. The analogy between her posture and that of Sintenis' Daphne was obvious: Renée Sintenis made twigs and leaves grow from Daphne's arms and armpits and moulded her hair into a treetop, her arms also reaching for the sky. The title Daphne refers to Ovid's tale Metamorphoses, in which the nymph Daphne is transformed into a laurel tree to escape Apollo's courtship and thus becomes invisible. In Sintenis' work, Daphne is also a figure in between worlds: between organic nature, being human, and gender.

In her performative lecture, Szepanski connected the wavering between visibility and invisibility with Sintenis' biography and the prestigious location at the University of the Arts. Until 1919, Renée Sintenis, like many other women, was not allowed to study at a German art academy, so she studied in freely accessible courses. In the 1920s, she sculpted small animals such as deer, donkeys, and dogs in an attempt to counter the monumental sculptures of the male sculptors of the time. She sold these works internationally. Defamed as a 'degenerate artist' during the years of the National Socialists, she did receive commissions again after World War II, but not for sculptures in urban spaces like her male colleagues, who were now working abstractly and monumentally. In the mid-1950s, Renée Sintenis was offered a position as a professor at what is now the University of the Arts, which she gave up in the same year. Such institutional recognition came too late in her life. Birgit Szepanski's performance and lecture visualised these invisible ambivalences and contradictions. According to Szepanski's artistic utopia, the sculpture Daphne might stand on Steinplatz today as a symbol for art history and politics. Depicted with the body and set in motion, the performance temporarily changed the site and smuggled a feminist narrative into the city.

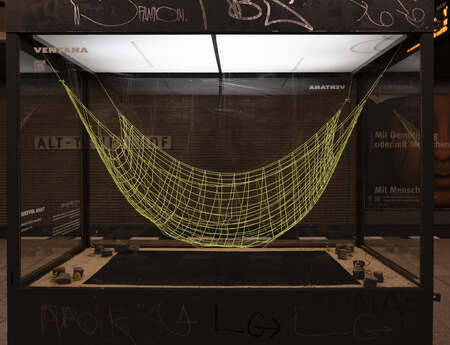

The performance dedicated to Tina Haim-Wentscher (1887-1974), now unknown in Germany, took place in an aviary garden near the Memorial Church. This is where, according to Szepanski's research, the Lewin-Funcke School was located from 1901-1938, a private studio for drawing and modelling that female artists were allowed to attend. Haim-Wentscher attended classes there for two years. She became famous in Berlin for her sensitive portraits in stone or wood of the actress Tilla Durieux and the sculptress Käthe Kollwitz, and she was awarded numerous commissions. The performance adopted Tina Haim-Wentscher's depictions of female couples: Birgit Szepanski, together with artist May Ament, visualised the sculptures Renate and Lola (1923) and Two Dancing Balinese Girls from the 1930s, which Haim-Wentscher created while travelling in East Asia. The sculptress stayed there to escape the Nazis. She later lived in Australia, where she became a well-known sculptress.

The 'sisterhood' that features in Tina Haim-Wentscher's sculptures is also a motif used in Moving Female Sculpture. The female sculptors, who paved the way for the following generations by virtue of their artistic courage and independent work, became present for the duration of the performative lectures, and their sculptures came alive. Especially with female sculptors such as Tina Haim-Wentscher, Christa Winsloe, and Sophie Wolff, whose lives were characterised by numerous ruptures, the performances evoked a sensitive closeness. Many of the works of these female sculptors have been lost. The performance showing Christa Winsloe's (1888-1944) animal sculptures at the Zoological Garden, where she used to draw in front of the animal enclosures in the 1920s and also model animals in plasticine, created a dense atmosphere. While Birgit Szepanski and May Ament re-created Christa Winsloe's lost animal sculptures, animals from the Zoological Garden were to be heard and smelled.

At the Georg Kolbe Museum, another performative lecture took place in the museum garden, which is open to the public. In addition to numerous sculptures by Georg Kolbe and other male sculptors, a sculpture by Louise Stomps can be found at the edge of a flower bed at the back of the garden. At the side of the front garden is a sculpture by Jenny Wiegmann-Mucchi. In her performance, Birgit Szepanski drew particular attention to the peripheral positioning of these sculptures. She brought the widely spaced sculptures together by means of a performative walk through the museum garden. In doing so, Szepanski touched the wall of the museum building with her body and her hands. She felt her way along it, thereby referring to power relations between male and female representation in museums and collections.

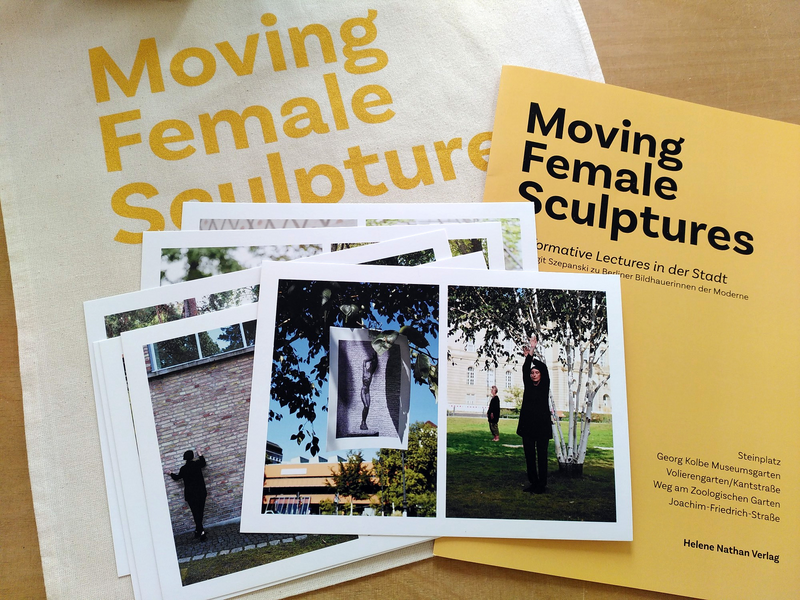

A three-part publication was issued by Helene Nathan publishing house along with Moving Female Sculptures. A cotton bag, seven postcards, and a text booklet invite readers to visit the locations of the performative lectures and embed feminist narratives in the city.

Author: Birgit Szepanski

German - English