The Psychology of Experiencing Art

Here at Sculpture Network, 2025 has been the year of emotion: we have talked a lot about what we feel when we look at art. Now, let us get scientific! There is a whole field of research dedicated to looking at our brains while we look at art.

A little while ago, I stumbled upon an article discussing the science behind our emotional responses to art. Researchers raised the question whether our reactions are, to a certain degree, universal. At first, I was sceptical: is the emotional response to a particular work of art not too individual to generalise? After all, it depends on many factors: current mood, individual experiences, personality … But then, I thought a little further: Why is it that certain works of art seem to elicit such similar emotions in millions of different viewers? Why do we all think of the Mona Lisa’s smile as enigmatic? Why do so many of us feel that specific type of yearning when looking at Rodin’s Kiss? We do accept that reacting to art on an emotional level is a universal experience. At the same time, we assume that one person’s reaction is absolutely unique. And it probably is, since no two humans are alike. But are our emotions really that different from each other?

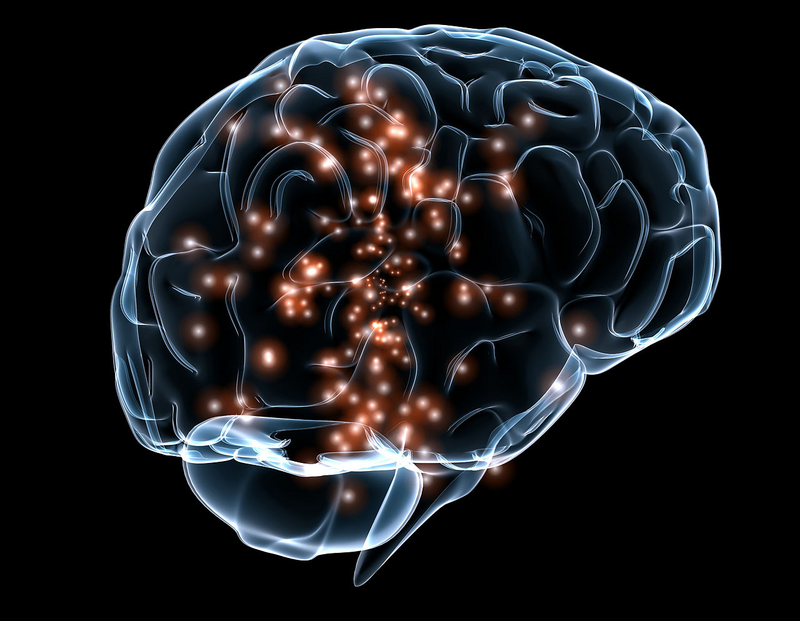

I could not shake these thoughts, so I dug a little deeper – and discovered a whole area of research. The field of neuroaesthetics uses scientific methods from neuroscience, psychology and other disciplines to analyse what happens in our brains when we look at art. Finding out which areas in the brain are activated when engaging with art is only one of the possible approaches (interestingly enough, the amygdala, responsible for emotional responses, appears to be involved). Researchers are looking for patterns in what humans consider aesthetically pleasing or, more importantly, whether certain artworks can develop transformative power over viewers. The field is alive and bustling: In the past few years, numerous studies using different approaches have been published. I looked at two of them.

The Museum as a Scientific Playing Field

Being pulled into a scientific experiment is probably the last thing anyone expects when visiting an art exhibition. Yet, recently, quite a few studies have been conducted in museums to find out exactly how people react when engaging with art in its natural habitat. Psychologist Matthew Pelowski from the University of Vienna, along with his colleague Stephanie Miller and others, has designed an experiment to probe into the idea of a shared human experience in response to art. Are there aspects of our individual art experience that are more universal than we think? The researchers asked visitors of the Albertina Museum in Vienna to answer questions concerning their emotional state before and after visiting a specific exhibition room. Their questionnaire included emotions typically associated with art – positive and negative alike – as well as everyday emotions: amusement, boredom, disgust, epiphany, fear, joy, relief, wonder … The rooms were carefully chosen beforehand to allow for different emotional experiences: One room housed impressionist paintings, another abstract paintings by Gerhard Richter, and a third one large collages/prints by Anselm Kiefer. By including figurative as well as abstract pieces and varied themes expected to elicit positive or negative emotions, Pelowski, Miller and their team hoped for a broad range of different reactions. (On a side note from a laywoman: Does this choice in itself not imply that there is some sort of shared perception? None of us would think of an impressionist painting as disturbing or of a Kiefer piece as light-hearted.) The 345 participants of the experiment were people from all walks of life: aged 18 to 87, Austrian or German citizens and international tourists alike. The only thing they had in common: they all had decided to visit the Albertina museum on this particular day.

As one would expect, the individual responses of each visitor were wildly different. Some spent barely half a minute in their assigned room; some took their time. Some reported having felt strong emotions; others were rather unimpressed. Maybe most importantly, some participants reported a change in their mood after their visit, while others felt unfazed. At first glance, this might suggest that the answers were all over the place. But when looking at the whole group, the researchers saw an interesting pattern: five profiles emerged, each associated with a different set of emotions. People could feel repulsed or challenged by the art, they could feel at peace, they could feel transformed, but they could also feel nothing much at all. The researchers called these different profiles Classic-Negative, Social-Negative, Harmonious, Transformative, and Facile/Neutral. As different as each participant’s questionnaire looked, they could all be placed in one of these groups. This led the research team to believe that there are in fact patterns in our interaction with art.

However, this does not negate the uniqueness of our experience. As individuals, we each react differently to different works of art. But as a species, we seem to have a pattern. What I found most striking about the study’s results was that in the negative groups, people often reported feeling a strong sense of meaningfulness and transformation. People in the facile group reported only low levels of each emotion and hardly any sense of transformation. This speaks volumes: the power of art unfolds through the strong emotions it evokes, whether they are positive or negative.

A Museum Visit with Electrodes on Your Head

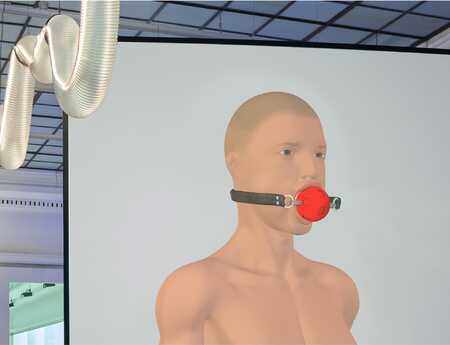

If you think being questioned about your emotional experience in a museum is unorthodox, wait until you hear about the experiment conducted in the Mauritshuis in The Hague, home to Vermeer’s famous Girl with a Pearl Earring. The researchers sent their test subjects through the exhibition wearing an EEG cap and mobile eye-tracking equipment. Thus, they could measure brain activity and record which elements of a particular work of art participants focused on in what order and for how long. Afterwards, an MRI scan was conducted to see which specific areas in the brain were responding. What they wanted to know: Is there a difference in emotional response when looking at the original instead of a reproduction? What neurological processes happen when engaging with art in a museum setting?

To approach this question, participants were shown the original of Girl with a Pearl Earring and four other paintings as well as original-sized poster versions of the same works. By looking at the data from the EEG, the eye-tracking and the MRI, researchers could determine specifics about the emotional state of their test subjects. The EEG does not show which areas in the brain in particular are involved, only whether there is more activity in the right or the left half. Activity on the left side indicates a wish to approach; activity on the right side indicates a wish to avoid. That means our brain decides in split seconds whether we have the urge to engage with a work of art or pass it by. In the case of the Girl with a Pearl Earring, the measurements showed a ten times higher urge to approach the original painting compared to the print. Similar results – albeit not quite as strong – could be observed with the other paintings included in the study. But there was something else that made participants linger in front of the Girl: the eye-tracking revealed that the viewer’s gaze is (as usual when looking at people) first drawn to her eyes and lips, but then also to the prominent namesake earring. Viewers keep looking from the eyes to the lips to the earring and so forth, as if caught in a loop. The longer we look, the more familiar the painting gets – and the human brain likes familiar things. That is part of the reason why the reactions to the Girl with a Pearl Earring are so overwhelmingly positive.

And now? Did we solve Art?

What does all this mean? Is science about to decipher the complex riddle of the human interaction with art? Probably not. The studies presented in this article do have their limitations: For one, they do not take into account cultural differences. Would the results differ if participants were confronted with art from another cultural background than their own? And what about the way in which emotions are described: Does language have an influence on the way emotions are expressed? In the Albertina Museum study, we can assume that some tourists were asked about their emotions in a language that is not their mother tongue – are these answers precise? Also, the research team only questioned people who were already on their way to visit an art exhibition. What about all those others who have never seen a museum from the inside? Would they answer entirely differently?

Among sculpture enthusiasts, one shortcoming probably stands out the most: The bigger part of experiments in neuroaesthetics so far are conducted using two-dimensional art. Maybe because it is more readily accessible, maybe because paintings are the first category that pops into people’s minds when they hear the word “art”. I wonder whether the emotional reaction to a sculpture or, even more striking, land art, light art or all kinds of installations would be different, maybe even more powerful. What happens in the human brain when confronted with a figurative sculpture such as Michelangelo’s famous David? Or the monumental statues of the Vigeland installation in the Frogner Park in Oslo? Does our brain activity on the left side go through the roof because we recognise not only the sculpture itself but also the intimately familiar human form?

I imagine there will be different reactions among art lovers to this kind of research: Do we have to explain everything? Is it necessary to understand the exact physiological and psychological processes to appreciate the power of art? Does it destroy the magic? I would argue: it does not. To me, understanding that there is some kind of shared experience does not diminish my individual experience. On the contrary, it makes me feel closer to my fellow humans, knowing that there is something deep within us that resonates in a similar way when we look at art. The thought that the way we are touched by a painting or a sculpture is universal, to some extent, gives me a deep sense of belonging.

If you want to know more, look into the sources used in this article yourself:

Miller, Stephanie; Pelowski, Matthew et al. (2025): What Can Happen When We Look at Art?: An Exploratory Network Model and Latent Profile Analysis of Affective/Cognitive Aspects Underlying Shared, Supraordinate Responses to Museum Visual Art. Empirical Studies of the Arts, Vol. 43(2), pp. 827–876. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/02762374241292576

Mauritshuis, in collaboration with Neurensics and Neurofactor (2024): The unconscious emotions that art evokes. Neuroscience research into the impact of a museum visit. Final Report. https://www.mauritshuis.nl/media/soukluyo/report-neuro-mauritshuis-02102024_en.pdf

This article was written in English by Sophie Fendel.