A God Complex - Sculptorvox Volume 3

From Damien Hirst to Donald Trump, the arguable egotist or narcissist may exist in all walks of life, but not least of all in the world of art. Both individuals feature in the work presented in the latest volume of Sculptorvox: A God Complex. The third title to be released in a planned series of eight volumes, "A God Complex" is used to emote and effect a response; to delve deeper into the human condition, our foibles, tendencies, and limitations. It highlights underlying notions of elitism, superiority, separation, transcendence, narcissism, appropriation and an essential desire to apply meaning to what might otherwise appear existentially empty…

We play a round of Top Trump with LA based South American artist Julio Orta, ruminate on the machinations of Damien Hirst beneath The Bust of The Collector with Alex Baddele, and take a long view on the art of using other’s work through the lens of Puppies Puppies by Hannah Nussbaum in Mr Potato Head.

From original pieces of writing, to photographic work, art, interviews and sculpture, we take a broad and eclectic look at the processes and inspirations for the contemporary sculptural artist.

Dr. Nicola Donovan, Sculptor and Author, wrote a review for sculpture network:

The current issue of Sculptorvox is a collection of essays, reviews, interviews, creative texts, photographic works and images of sculptural works, that have in their sights the theme of "A God Complex". Defined as ‘an unshakeable belief characterised by consistently inflated feelings of personal ability, privilege or infallibility’, "A God Complex" is a very delicious and juicy theme; all that human ego, narcissism, creation, transcendence, allure, seduction, religion, and elitism offers a dark playground of edgy material for creatives to explore. It is also, given the astonishing antics and rhetoric of several current world leaders, a theme that is to the fore of the political landscape.

We might also regard the model of ‘expressive individualism’ as firmly in the ascendant, not only in politics but also in the impact and influence of omnipresent celebrity behaviour on our social selves. We are in a world where the deluded, over-privileged and inept gaze adoringly at their own image whilst driving the rest of us towards many versions of hell. Art in its many forms and expressions is needed right now to expose and check this pervasive, persistent, and dangerous manifestation of the ego beyond control. Quoting Nietzsche’s in the Editor’s letter “God is dead…what sacred games shall we have to invent?” Daniel Lingham also writes that ‘Artists are the Gods of small worlds’, which indeed we might very well be.

Therefore we perhaps have a responsibility to invent ways of presenting perspectives that challenge those which dominate our societies and cultures. Indeed, among the contributions to this edition of Sculptorvox are some incisive and acutely observed critiques that certainly do confront such dominant perspectives, as in the case of Alex Baddeley’s review Bust of the Collector. Baddeley has in his sights Damien Hirst’s 2017 epic museum exhibition Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable. Occupying two private museums in Venice this trickster show consisted of thousands of sculptures that Hirst claimed, tongue in cheek, to have helped recover from a historic shipwreck.

Baddeley notes an inversion of Hirst’s signature work whereby his presentation of clinical Modernity is imbued with holy stature and in this body of work, it is fiction presented as fact. Baddeley does not write a connection between the work of the secretive and enigmatic Banksy yet anyone who knows his work and had seen his 2009 Banksy versus Bristol Museum intervention would arguably do so. Although Hirst evidently has greater sophistication in terms of his philosophical and Art History references, both he and Banksy share a lack of technical and practical finesse when it comes down to making figurative, symbolic sculpture.

In fact, Baddeley goes as far as writing that although Hirst’s vast and lavish exhibition offered spectacle, acres of precious minerals and invitations to engage in knowing games of ‘spot the reference’ it actually lacked any artistry. On reading this review the question ‘is this a critique of contemporary decadence or a demonstration of the same?’ is answered by Baddeley’s analysis of the sculpture that seemed to enervate his critical view of this exhibition. Bust of the Collector is described by Baddeley as “grotesque” and with that he writes that Hirst presents himself as a “subject of adoration….here to be worshipped.” Always bombastic and provocative Hirst nonetheless has in his time produced affecting, relevant and at times very tender art.

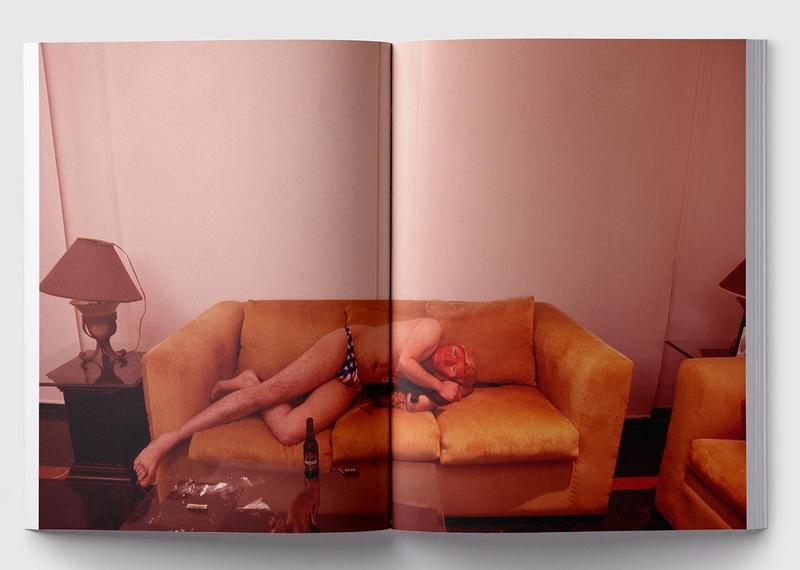

That he skilfully and cleverly manipulated the art market may well be beside the point. However, Baddeley’s piece precisely identifies "A God Complex" at work, perhaps occupying the ‘..God Shaped hole’ as attributed to Grayson Perry in this edition. Maybe Hirst is an easy target who set himself up for accusations of a delusional and messianic view of himself but he is an absolute rank amateur compared to the incomparable self-belief of Donald Trump. Julio Orta offers a series of photographs responding to words by Trump that imagine him as the subject, or model in what seems to be a Corinne Day style fashion story from the 1990’s.

Trump’s boastful soundbites are now familiar in the sound and text-scape, and perhaps we have become acclimatised, or inured to them. Orta’s isolation of them and response to them through images does enable a refocussing on the maniacally egotistical posturing that is a key feature of the ways in which this individual behaves. The lines “I’m very highly educated. I know words; I have the best words” along with “Nobody has better toys than I do” expose a child’s ego and an iteration of a potentially deadly superiority complex along with an immature perspective of himself amidst others. Orta’s images show a younger, slimmer Trump (a model in a latex Trump mask) clad only in star spangled banner briefs, reclining on a shabby, cat clawed sofa.

The guilty cat stands beneath a glass topped coffee table on which white powder has been chopped into generous lines, a rolled banknote lies next to them. Car keys and a bottle of beer are also cast onto the table and Orta’s Trump cuddles a soft toy beneath his neck. The lighting is dingy with an orange cast and the scene is, one of loneliness. In a second image Trump poses on a balcony, one leg lifted to rest on the balcony, exposing the hump that is contents of his briefs.

With the soft toy tucked under one arm he looks ridiculous, yet vulnerable and that begs the question ‘What on Earth made him this way?’ It is a question that is perhaps beside the point and does nothing to adjust his characteristic actions or approaches. However, to imagine him as Orta does in this set of work is to rise above judgements we may have regarding a dangerous God Complex with so much power to hand, and to acknowledge that there may be something other behind the mask. This is perhaps where humanity and a true sense of one’s own power and identity may be found, or not.

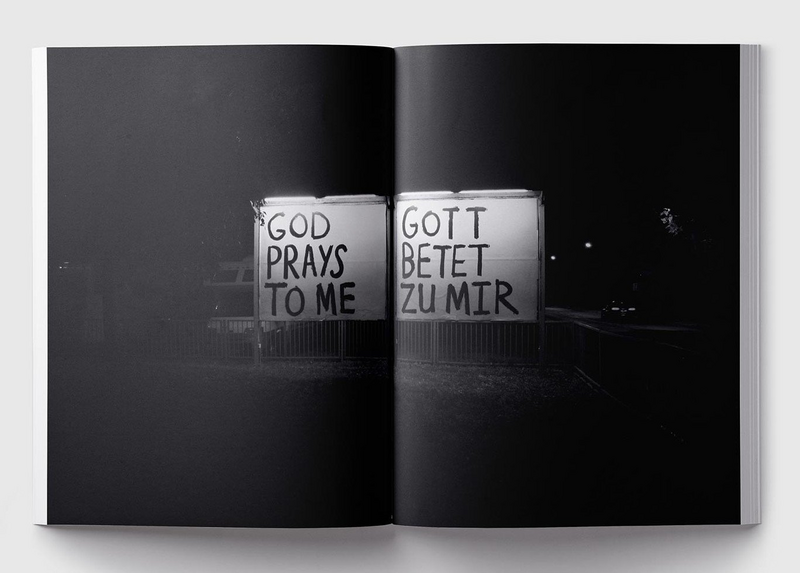

Following Orta’s contribution is the appositely sequenced, No Longer Can anything Exist in Isolation from Matthew Lloyd. Billboard sized sheets bear the letter ‘I’ repeated in hand painted, broad brush strokes and situated in an urban location is a billboard bearing the statement ‘God Prays to Me’. Again this is hand written in broad brush strokes, as if a host to the God Complex had shinned up a ladder and quickly defaced (or enfaced) a clean, prepared advertising hoarding. For A God Complex to function it cannot be in isolation, it needs others to recognise the hosts superiority and thus feed his or her delusion.

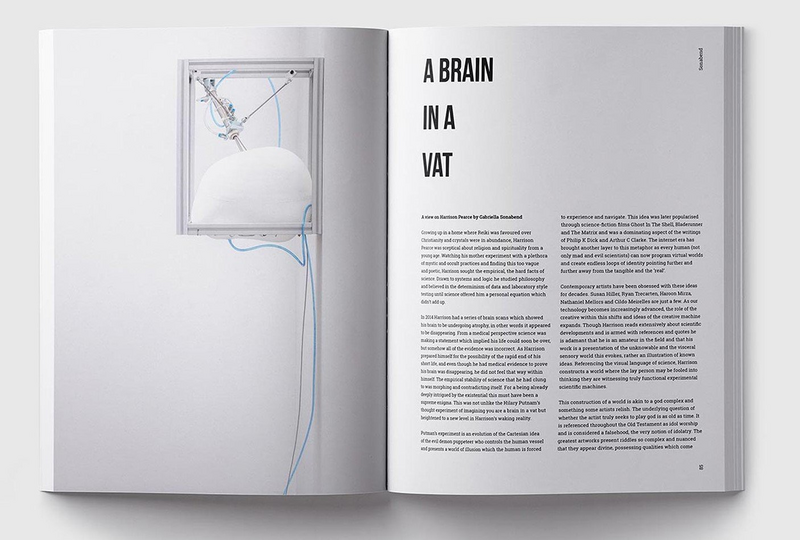

Lloyd articulates this as that which might be interpreted as desperate announcements that the host, the painter of these words, needs these words to read and accepted. Thus, with this work Lloyd exposes the Achilles heel of the God Complex. Among other critical writing are two outstanding pieces by Gabriella Sonabend, the first on the sculptor Patricia Piccinini and the second a view on the series A Brain in a Vat by Harrison Pearce. Both are sensitive, thoughtful and intelligent responses to each artist’s bodies of work.

Sonabend’s perception of each artists work is clear and in particular she situates Piccinini’s work within the context of other artist’s working in her field of contemporary figurative sculpture. Titled as Not Playing God - In Response to Patricia Piccinini Sonabend identifies a long history of artists making work intended to shock, unnerve, and disgust their audiences. She cites among these artists Goya, Hieronymous Bosch, the Chapman Brothers, Paul McCarthy, Sarah Lucas, Tracey Emin, Chris Burden and Santiago Sierra. But, Sonabend reads the works of the contemporary artists as loud, attention-seeking endeavours that do not penetrate the complexity of the subject matter they present and fail to understand the difficult questions contained therein. Sonabend appears to deem these artist’s works as chaotic documents, or ‘a mirror of the indecipherable fiction of politics’ and observes that they offer no counter narrative to guide a discourse beyond initial provocation.

By contrast, Sonabend speaks of Piccinini’s unsettling and uncanny work as whispering rather than shouting, of asking questions rather than making statements, and going deeper to a narrative that is ancestral and eternal, when others can only deal with the surface. Although as Sonabend writes, Piccinini’s work is about the how technology is altering our relationship to the human, it is a tender view of vulnerability, compassion, acceptance and love. For Sonabend there is no big ego at work in Piccinini’s sensitive rendering of humans caring for and safeguarding each other, this artist simply points to our innate humanity. Looking to a future where a new generation of babies have mutated to oversized but still vulnerable beings who have developed animal features, Piccinini touchingly depicts a ‘normal’ mother’s devotion to, and protection of her defenceless child.

Sonabend’s view of A Brain in a Vat begins by introducing Harrison Pearce’s spiritually esoteric bringing, which resulted in this sculptor’s allegiance to a scientific and rational approach to his visual practice. When Pearce received a diagnosis of brain atrophy, he responded with a sculpture series informed by a visual language of medical science, whereby the works masquerade as functioning yet fictional items of medical equipment. This engineered work has a comic aspect in its reference to Ikea store displays of furniture wear and tear testing, whereby a glass cubicle contains a chair that is continually thumped by a mechanical metal backside. It also has something of a contemporary Frankenstein’s laboratory merged with a hospital high dependency unit. Sonabend identifies this series as deeply connected to a universal questioning, which seems right given that Pearce’s diagnosis spells the imminent end of his short life. Sonabend’s writes her response to Pearce’s work acutely, sensitively, without being mawkish, and insightfully. Her conclusion is that Pearce’s work offers complex, beautiful puzzles designed to make us think.

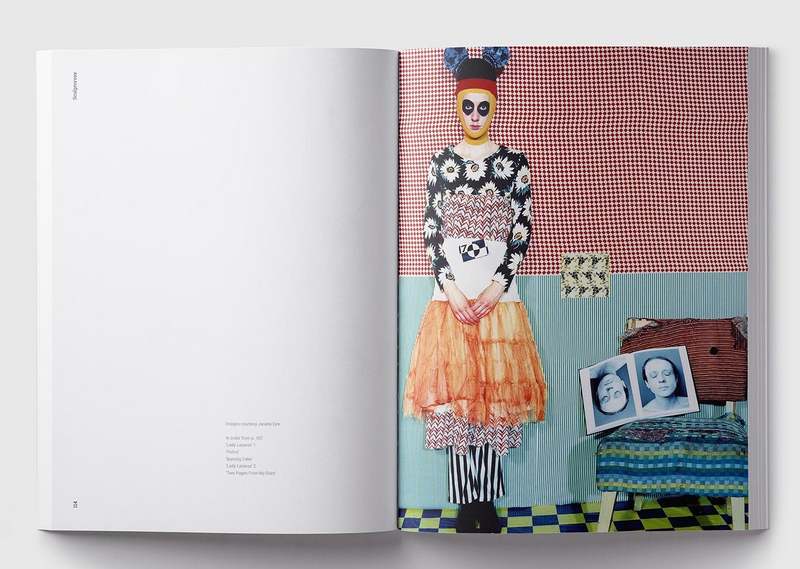

As well as critical pieces there are a number of short fictional texts of which that by Isabella Eyre is well worth reading. The Proposal is accompanied by a series of photographs that might be interpreted as part portrait, part edgy fashion shoot. The images, made by Janieta Eyre are heavily laced with Marian iconography and although interesting in their own right are not needed by the story itself. The Proposal is an engaging, dystopian tale that has a rich descriptive narrative. The story is intensely visual and free of the tedious illustrative detail that much writing suffers, instead Eyre manages to haptically induce a sense of what the characters see, feel and think. For example, on meeting a technician who administers psychological tests the protagonist of Eyre’s story states ‘His eyes hummed in their sockets like trapped houseflies’.

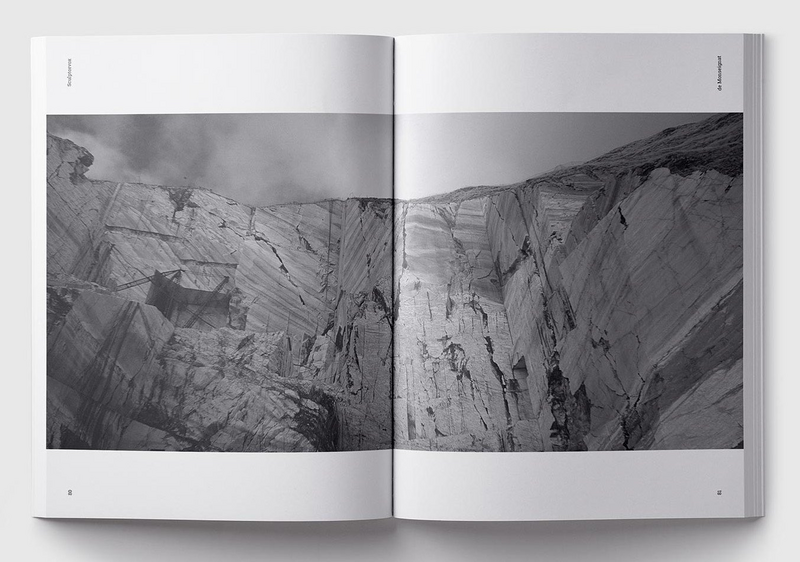

Graham Keddie’s In a Superposition is less entertaining and more of an essay on conceptualising an art practice, from a first person perspective. It is however a good read and Keddie’s identification of a ‘Fluid Phenomenology’ approach is a neat way of understanding multi channelled and splintered focus in the 21st century, as differently appropriate to the convention of singular, monolithic focus from the 20th century. He writes that he likes to have music, the TV, and maybe a screen or two flashing new arrivals to his inbox all going while he writes. Back in the day tutors forbade even personal stereos in Art School studios because they might distract the focus from being well and truly directed as a single beam. Images of Keddie’s artwork accompany the text and in this instance, and bearing in mind these are photographs of outdoor interventions in the landscape, his writing emerges as the stronger form and is needed here to support the visual work.

Standing alone however, are Hannah Honeywell’s photographs of her outdoor sculptural pieces titled Funambulist. Funny and tense, her Houdini-esque work employs a unifying colour pallete of black and red, along with blue skies and green vegetation. A chair dangles perilously from a sagging tightrope and an umbrella contraption suspended beneath another wire brings to mind old film footage of the brave and crazy tightrope walkers whose bodies managed to get them across the Grand Canyon or between skyscrapers. Other image only works also stand well; Michael Koch’s The Eternal Collection comprises images of birds and an illustration of what appears to be a fictional insect. Readers are directed to interpret the images as, ‘about the space between the imagined and the real’ and there is something of the Wunderkammer about Koch’s work in this edition.

Vasily Kononov-Gredin’s The Golden Calf is a work that, although it functions well in print would be a special treat to see in situ. Two enormous gilded horns occupy the centre of a high ceilinged gallery and emerge from a liquid, blood red, reflective floor. In its simplest iteration it is a representation of a three dimensional graphic image. However, imagined as a combination of essential materials with weight and smell and viscosity, this installation becomes monumental, symbolic and visceral. Like many of the artists featured in this volume, Kononov-Gredin’s contribution provides an introduction to his practice for those who do not already know it.

There are other artists featured in Sculptorvox 03 "A God Complex" who are well worth discovering in the volume itself. It is a carefully curated and edited publication that is beautifully put together. The standard of writing is very high and unlike many publications of this kind, it is a volume that one will return to again and again.

Author: Dr. Nicola Donovan

To learn more about Sculpturvox or to purchase the Volume 3 click here.