ReThink Collection

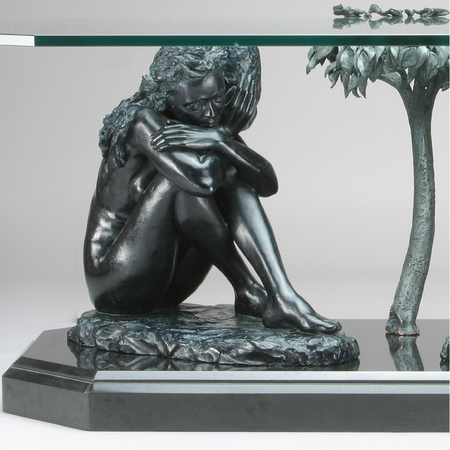

The Burden

That art, may comment on our society is considered by some to be the main objective of the artist. Within my work, I pursue purely aesthetic obligations, as a prerequisite, and independent of any voice that a sculpture may later find. I am hopeful, however, that I have achieved a certain aesthetic importance in “The Burden”, as well as having touched upon other matters of significance.

The sculpture portrays two figures each carrying upon their shoulders symbols of the responsibilities that have been placed upon them. One by nature, and another by the society of which they are a part.

Dimensions

Women/ Tree, Women/ Rock

Height 43 cm 43 cm

Width 29 cm 20 cm

Depth 45 cm 43 cm

Dimensions Base Marble Glass

Height 8 cm 20 mm

Width 52 cm 80 cm

Length 113 cm 140 cm

The Burden / The Glass Ceiling

In this sculpture, I have sought to represent the emotional and spiritual condition that has been the burden of women in patriarchal societies throughout history.

The sculpture consists of two seated female figures, each carrying upon her shoulder a symbol of the responsibilities that have been placed upon them, either by society, or by nature.

The first of the two figures represents the social, legal and religious obligations through which society has limited the freedom and rights of women. The second figure characterizes the specific role that nature has required of the female. I shall speak of each of these two figures separately, although they represent woman as one.

A women holds in her hands a tree representing the behavioral regulations that society imposes upon her. She has lowered her head in submission, her face hidden in the arms that support the symbol of her burden. The apple tree alludes to the story of Genesis; of paradise lost to man by the actions of a woman, and speaks of the responsibility for the original sin; and the disobedience to God. “God expelled both of them from Heaven to earth,” and bequeathed their sin to all of their descendants, as God had never forgiven their disobedience.” Thus, Eve bears the responsibility for herself, as well as for Adam, and the “original sin” of all humanity.

The Islamic scriptures portray a more egalitarian society, where women are considered equal with man and each is equally to blame for their disobedience to God. “Together they asked God for forgiveness and He forgave them both.” Further, there is little inference, in text, that women are considered untrustworthy or to be of ill nature. Although this doctrine decrees a greater equality under ecclesiastical law, in practice the women of these societies are denied many basic rights.

Legal authorities in most societies throughout history have formally restricted the rights of women. Both canon and civil law held that women in Europe and North America were not recognised before the law and thus were denied many privileges. The English crown held: “That which the husband hath is his own. That which the wife hath is the husband’s.” This formally denied the female the right to hold any property to which she maybe entitled, and before the law she became a possession of her husband. These rigid boundaries prescribed the female’s role within the culture; having been denied a legal identity, no act by her was of binding legal value. Until the end of the Nineteenth century, the denial of judicial position prevented women from voting, giving evidence or bearing witness in the Western world. Even today, some Israeli courts repudiate the testimony of women.

As a matter of law, civil authorities of the Roman Empire mandated an agreement based on property rights as a condition for recognizing a marriage. Likewise, Jewish tradition has legally regarded the female based on the concept of property and the possession thereof. The act of marriage represents the legal transfer of possession and responsibility for the female, from the father to the husband. Further, both the Old Testament and Islamic doctrines confine inheritance rights exclusively to the male relatives, recognizing no rights for widows or female offspring.

Prejudices against women can take several forms within social and domestic structures, causing a daughter to be considered an ethical or financial liability to her family. Some societies place extraordinary value on the sexual purity of the female, which if compromised would diminish her potential worth as a bride, wife and mother. The murder of a female for a moral offence of this nature, is frequently over looked by the authorities in such countries as Pakistan, Iran, Jordan and Saudi Arabia and may result in only cursory punishment in many other Islamic states. In some societies, a female child may threaten such economic hardship that infanticide, although considered illegal, offers a common solution. The one child policy in China presents an example of politically inspired behaviour that is considered a contributor to female infant mortality. Although difficult to verify, infant mortality rates have a tendency to appear biased toward the survival of male children, with dysentery, dehydration and tuberculosis claiming a disproportionate number of female infants in the poor rural areas of China and many Islamic and third world countries.

Another discrimination, to which the female is subjected, is the physical and psychological anguish that accompanies genital mutilation. Maintained by tradition, this act subjects the female to unnecessary risk while providing no benefit to either the individual or to the society.

The disadvantages that women face include the loss of opportunity through lack of access to education, denial of the right to posses resources and property, as well as the recognition of identity before the law. Clearly, without the recognition and respect of society, the female has little hope of accomplishment or position. She will continue to have very little influence in the affairs of her community, thus denying her the possibility of breaking this historic cycle.

The second figure sits erect and shoulders her charge with determination and dignity. The stone is symbolic of the obligation, the liability and the consequence, which accompanies pregnancy, birth, and childcare.

The stone represents the corporal burden involved in the females’ responsibility for procreation, and extends further than the normal health risks to include the liability of being physically vulnerable to her male counterpart and thus less able to protect herself or the lives of her children. Further, she may be unable to shelter herself from sexual assault, thereby including the inherent responsibility of caring for illegitimate or abandoned children.

The glass cover binds the two figures and alludes to their condition, their spirit, and their common purpose. They share an uncertain destiny with equivalent and related afflictions. Further, the glass surface assists in reminding the witness that, as in all things we observe some transparent lens always serves to influence and distort our vision.

The third element in the work represents the “tree of life” and in addition to providing stability to the glass tabletop, it symbolizes this the greatest of gifts.

Much of women’s burden was created by men and sustained by tradition, only that which was granted by nature is worthy of womankind.

References:

Leonard J. Swidler, Women in Judaism: the Status of Women in Formative Judaism (Metuchen, N.J: Scarecrow Press, 1976)

Thompson, Women in Stuart England and America (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1974)

Matilda J. Gage, Woman, Church, and State (New York: Truth Seeker Company, 1893)

Sally Priesand, Judaism and the New Woman (New York: Behrman House, Inc., 1975)

Dr. Sherif Abdel Azeem Women in Islam versus Women in the Judaeo-Christian Tradition.

The Burden

One of the influences that has for many years been present in my work remains the Caryatid, originally found in both Egyptian and Greek architecture, it is defined as a sculptured female figure serving as an ornamental support in place of a column or pilaster. Among the most celebrated examples of this type of architectural decoration is the Porch of the Caryatids, forming part of the Erechtheum, the temple found at the Parathion in Athens. Here six beautifully sculptured figures, acting as columns, support an entablature on their heads.

It is difficult to say how much of the sculpture created by August Rodin has affected my work, however within “The Burden” the figure supporting the rock has been placed in a pose that echoes the “Caryatide Tombee Portant sa Pierre” created in 1893. Although I choose to represent the figure in an attitude that was not as exaggerated in order to provide the impression that the figure was better able to carry the weight of her burden. This work by Rodin served as the original idea for the position of the figure as well as assisting in the determination of the charge that she carries.

This sculpture follows a reoccurring theme in my work. Whether my bias towards the female form is aesthetic, cultural, or a gender preference, I am unsure. However, the female form makes up the majority of the figures within the totality of my inventory, and here is presented in the most complete and intricate form.

I have considered this piece as a portrait of Women, and have represented her with a greater emphasis on her mental than physical condition. Further, I refer to her position within many societies and both the evolving and the perpetual circumstances in which she has found herself through out history.

In this century, the place that women are allotted within this world will be redefined as a consequence of globalization and the resulting mixture of cultures.

The migration of over a million refugees into Europe is bringing this change to the attention of the media and greater general awareness in the first world.

A large part of the European population has realized that the manner in which women are treated in their culture will require the re-examination of some social and religious considerations.

Throughout history there have been a vast number of responsibilities that have been placed upon women by society, by nature and by differing mythologies or religions.

There are social, legal and religious obligations, which for the most part, have limited the rights and freedoms of women, and then there are specific roles that mother nature herself has required of the female.

In most societies both legal and theological authorities have formally restricted the rights of women.

Both canon and civil law once held that women in Europe and America were not recognized before the law and were thus formally denied the right to hold property.

Although this is no longer the case in the first world, it remains so in Islamic countries today.

The civil authorities of the Roman Empire mandated an agreement based on property rights as a condition for recognizing a marriage.

Although, to this day, in varying degrees, both Jewish and Islamic traditions regard the act of marriage as the legal transfer of possession and responsibility for the female from the father to the husband.

Both the Old Testament and Islamic doctrines confine inheritance rights exclusively to the male relatives, recognizing no rights for widows or female offspring.

Until the end of the Nineteenth century, the denial of judicial position prevented women from voting, giving evidence or bearing witness in the Western world.

Even today, some Israeli courts and all Islamic courts repudiate the testimony of women.

When considering religious doctrines, we can begin with the story of Genesis; that tells of paradise lost to man by the actions of a woman and the resultant “original sin” conferred to all of humanity.

Some societies place extraordinary value on the sexual purity of the female, which if compromised would diminish her potential worth as a bride, wife and mother.

This places an extraordinary ethical liability on her family and imposes extremely restrictive social rules and behaviour.

The murder of a female for a moral offence of this nature is, in some cases, over looked by the authorities in some Islamic countries and may result in only cursory punishment in many other Islamic countries.

In some societies, a female child may threaten such economic hardship that infanticide, although considered illegal, offers a common solution.

The one child policy in China offers an example of politically inspired behaviour that was considered a contributor to female infant mortality.

The disadvantages that perhaps as many as a billion women face include the loss of opportunity through lack of access to education, denial of the right to posses resources and property as well as the recognition of their existence and identity before the law.

Then there are the corporal burdens involving in the responsibility for procreation, that extend further than the normal health risks to include the liability of being physically vulnerable to her male counterpart.

This disadvantage may deny her the capacity to protect herself or the lives of her children.

Further, she may be less able to shelter herself from sexual assault, thereby including the inherent responsibility of caring for illegitimate or abandoned children.

With this changing century we need to assist in the re-examination of the legal and social elements that are potentially restricting one half of the world’s population.

The greater part of women’s burden has been created by men and is sustained by tradition, only that which was granted by nature is worthy of womankind.

By Blake and Boky

Bibliography

- Leonard J. Swidler, Women in Judaism: the Status of Women in Formative Judaism (Metuchen, N.J: Scarecrow Press, 1976)

- R. Thompson, Women in Stuart England and America (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1974)

- Matilda J. Gage, Woman, Church, and State (New York: Truth Seeker Company, 1893)

- Sally Priesand, Judaism and the New Woman (New York: Behrman House, Inc., 1975)

- Dr. Sherif Abdel Azeem Women in Islam versus Women in the Judaeo-Christian Tradition.

- Leila Badawi, “Islam”, in Jean Holm and John Bowker, ed., Women in Religion (London: Pinter Publishers, 1994)