The Stones Waiting at the Bottom of the Valley

It’s remarkable. A centre for contemporary stone sculptures in the middle of the mountains. In the summer of 2021, under the title of “Las piedras saben esperar,” Jose Dávila conceptualised the opening of the “Centro Internazionale di Scultura” exhibition in the Swiss canton of Tecino.

The bus was regular; seven times a day between 8am and 7pm. It took almost 1½ hours for the delivery van to travel the 40 kilometres from Locarno, on the northern shore of Lago Maggiore in Switzerland, to the upper Maggia valley. Here, almost 850 metres above sea level, grey rocks characterise the backdrop, which piled up as the alps were forming around 20 million years ago.

The centre for stone sculpture, exhibitions and art is on the outskirts of Peccia, an area in the region of Lavizzara. Planned by the Tecino architects Bardelli Architetti Associati (Michele and Francesco Bardelli, as well as Davide Moranda), and conceived by Almute Grossmann-Naef and Alex Naef, directors of a 30-year-old sculpture school, the project was realised with the generous support of public donors, private sponsors, and patrons. Located in a village with just under 200 inhabitants, the “Centro Internazionale di Sculptura” aims to be a new space for meeting and communicating, offering a studio, workspace, exhibition centre and stage.

Architect Jose Dávila, a sculptor who studied under Mexican Pritzker Prize winner Luis Barragán, places ten sculptures in the central exhibition hall, the workspace, and the forecourt of a church in the nearby hamlet of Mogno that was designed by the Ticino architect Mario Botta. The sculptures are both fragile and expansive, playing with physical forces and at the same time referencing the white stone of Peccia; a huge mass of limestone formations that came under pressure in the process of folding of the Massif Central, and then crystallised due to the resulting heat. The result of this process is a coarse-grained, compacted marble that presents in a variety of colours from whitish-ivory to grey, greenish, brownish to a dark grey-white, and textures from light streaks to clear, bold banding.

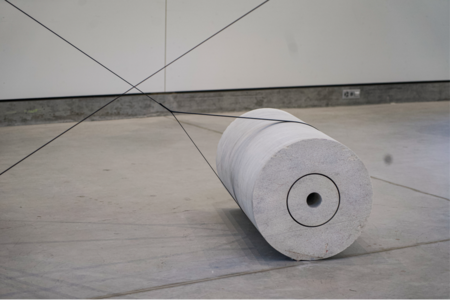

Joint effort, 2021, Peccia marble, gneiss rock and tension belts

Jose Dávilas used both natural (light marble and grey gneiss) and industrially manufactured (concrete, bronze, fibreglass and tension belts) scraps, using many different methods to manufacture the sculptures (precise cuts from a saw, laboriously cast iron, accidentally-found river pebbles, and precise calculations). On one hand the works mirror the symbolic (artistic) worth of different materials, but on the other, they represent the sophisticated balance between borderline light state of uncertainty and the realistic heavy force of gravity. Dávilas makes use of the forms and elements of 20th Century constructive, concrete and conceptual art: dots and lines, surface and space, static and moving. He creates an artistically arranged, paradoxical and always fragile, effective three-dimensional system which, alongside the obvious tension, also convey great peace, and yet always seems to stand in rather uncertain territory.

The sculptural installations are based on what only seems to be a harmonious whole and always thematise visible contrasts as well: natural stone or art materials, difficulty or ease, fixed or moving, location or change. Jose Dávilas thus precisely and topically addresses a process of accelerating change that can be observed in many areas of today’s society. He raises questions about a location that is undeniably vital for all people and their human identity. His stones know to wait. They do not move. They move the viewer, and are thus a vivid answer to the overbearing uncertainty of a present that is becoming increasingly confusing.

Translation: Hannah Griffiths

Published in March 2022

Cover picture: There is always a question to be found at the end, 2021, Peccia marble and boulders