International Dialogue in The Hague

On 9th June, an international group of art enthusiasts met in The Hague. It was a day filled with art, and was both organised and run by artist Yke Prins, a member of the sculpture network board.

As I entered the grounds of Voorlinden, everything was bathed in the greenery of early summer, and as through that greenery ran a line of sculptures by Antony Gormley. The bodies were arranged one after another, the different postures and positions of the bodies making it look like they were dancing.

All of the participants of the event gathered in the restaurant lounge and put their catalogues on the prepared table and before long, the room was filled with intense discussion.

The Voorlinden Museum’s curator gave a short introduction to Antony Gromley’s current exhibition. She began with a quote from an artist: “To move the body is to move the mind.” In the garden earlier on, I had put myself into the position of the sculpture that was bending of a wall and did experience that it moved me. In order to enjoy the exhibition in its entirety you have to move around – because the sculptures are also spread across the garden, the forest, and the bordering dunes.

The museum’s modern building is flooded with light from all sides, and from above, with sloped tubes guiding the daylight through the glass ceiling in the exhibition room.

The tour started in the stunning library. Walls several metres in height were covered in filled shelves, containing books by every artist in the collection and literature on contemporary art for study.

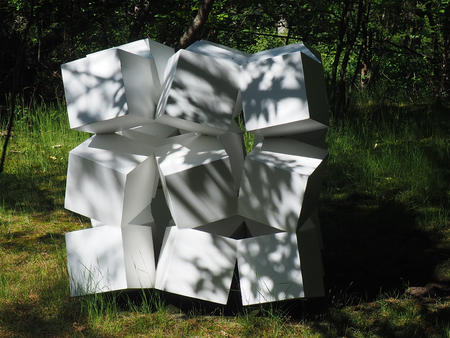

Voorlinden puts giving artwork enough space high on its list of priorities. The “contract” room was even more oppressive, filled with bodies constructed from cubes. The form was still recognisable in some, but the cubes Antony Gormley had scaled up lost their form even more.

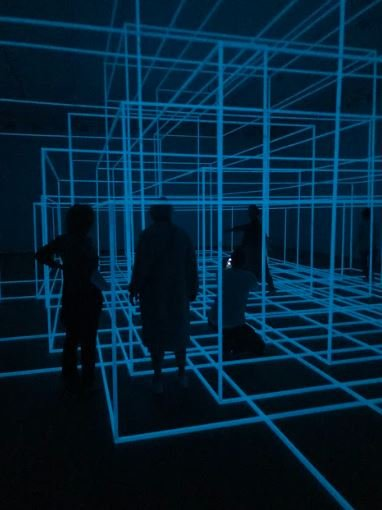

Some of the sculptures invited action, such as “Clearing,” a 7km long steel band that took over the space with intersecting circles. Step by step, feeling my way forwards, bending and turning, I moved through the sculptures without touching them. For two of the participants the work “Passage” was even more intense. An abstract outline of a person was formed in a 12-metre-long tunnel that was closed off at the end. Walking forwards into the darkness, the fading of the outside world, orientating yourself using your own sound – it touched and moved them both. The comments made illustrate how profound of an experience it was: “If you are in darkness, you feel like you become the darkness.” “As I neared the end, I expected complete darkness, but there was in fact light before the turning point.” The wall the participants were walking towards was painted in another colour so that the little light was reflected, an experience that was excellently composed.

In contrast, I experienced James Turell’s “Skyspace,” a square, wood-panelled room with benches along its walls. If you looked up, you could see a square slice of the sky that happened to be a radiant blue on this particular day. The sky framed as a picture. The ceiling was of course also open to rain, snow, cold. A changing experience of the room…

Walking through Richard Serra’s “open ended” brought back memories of the SN trip to Bilbao. Filled with impressions, we stepped back into the garden, taking in the soothing greenery like a sorbet for the eyes, as an intermediate course within the rich menu of art.

Sandwiches were waiting for us in the lounge and music from the choir swelled once again; the creativity in the room was electric.

At 3pm we walked another 100 metres to the Clingenbosch sculpture. The Kaldenberg family lived in the stately home, whose garden can be viewed on Thursdays. After a cup of tea we started on a 2.5km walk through the forest. We encountered the sculptures between cushions of moss, rhododendron bushes and old trees.

A fragile, blue column of light, “Argon” by Bill Culbert, poked its way up between firmly rooted tree trunks. Or is it a beam of light from top to bottom? Jos Oehlen’s “Vrowenfiguur” was stood a little further on, aligned between heaven and earth

A small path through the dunes took us past “27 kubussen” by Erik van Spronsen, where shadows of the trees danced on white cubes.

John McCracken led us through a world of mirrors with “Teton” until I began to ask myself, “where is the real world?”

On the large lawn in front of the house laid “Lage Four Piece Reclining Figure” by Henry Moore. It appeared unapproachable to me, a landscape that ought only be touched with the eyes. It was easier to touch the sculpture “Slow,” which was by artist duo Fortuyn and O’Brian. This is obviously only a very small and subjective selection of the artwork this garden houses. Over wine and nibbles, we rested our feet and eyes before the iron gate shut behind us again.

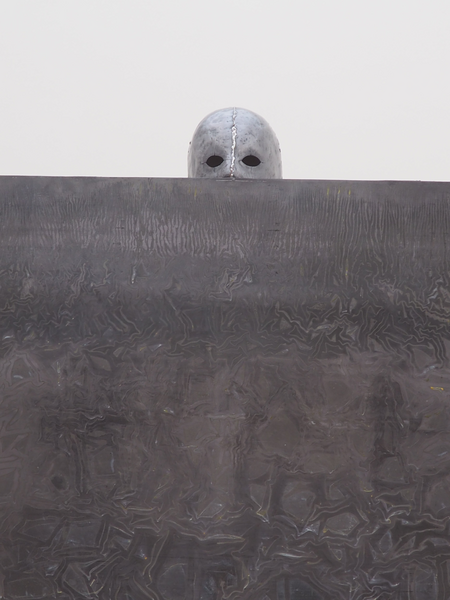

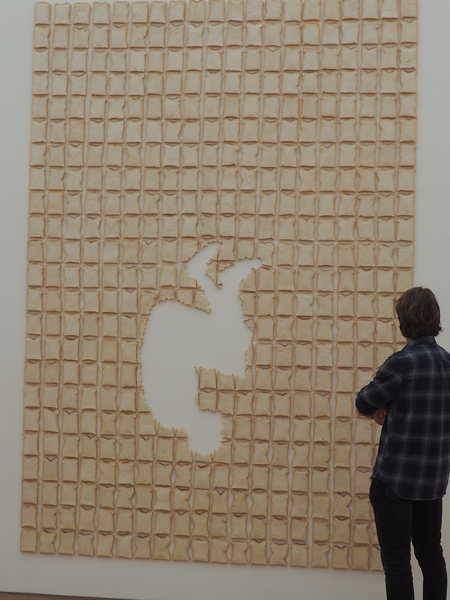

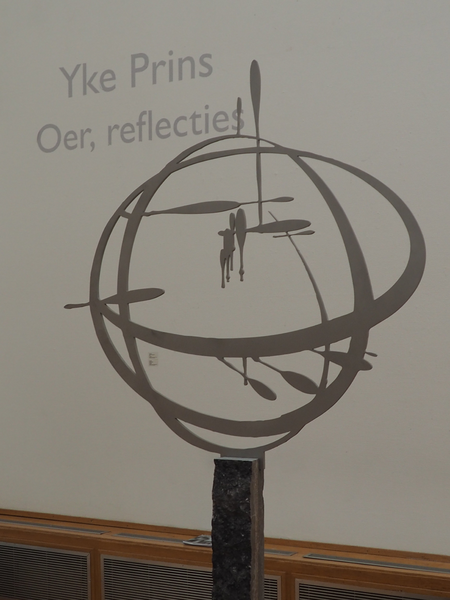

Our final atop was in the centre of The Hague, the Pulchri Studio artist association. In the Weisenbruchzaal we admired the works of Yke Prins. The exhibition Oer, Reflectires, curated by Ien van Wriest, celebrates the 40th anniversary of Yke Prins’ artistic life. The word “Oer” (UR) resonated with me strongly, a reflection of our primal roots from which art, perhaps everything, arises, as is represented by “Oer.” Two other central sculptures, “Oerschreeuw” (Primal Scream), immediately caught my eye. One in wood with a lively, moving surface and next to it, the other in bronze which transformed into clear lines. Transformation could be seen elsewhere too, where meditative calligraphy became feather-light steel sculptures. Some floated above us as mobiles. I felt the deep rootedness of this lightness which impressed me.

Being in nature, drawing from it, creating shapes with it, means a lot to Yke Prins. She said that “the centre has been formed by nature, the outside by Yke.” Prins reflects on her art in conversation with other in a successful book. It was produced during the period of Covid and rounds off the exhibition.

At dinner I thought: what a fulfilling day! There participants were touched by their intense encounters with the sculptures, and opened up for a very personal exchange.

Translated by Hannah Griffiths, published in June 2022