Liebes Ding - Object Love

The exhibition "Liebes Ding - Object Love" displays the relationship of humans to the things surrounding them. Our author Eva Daxl will take you with her to the currently unfortunately closed exhibition.

What is a thing? And do I need it? Thoughts on the subject of "thing"

Most people own more things than they need to live. For every person there are special things that they love more than others. But also equal and even identical objects are loved differently by people. So It was found that people considered the things they owned to be more valuable and of higher quality than the exact same things they did not own. This means that people establish a relationship with the objects they own and value them more than identical others they do not own.

Another aspect of surrounding oneself with things is that things reflect the personality of the owner and express their own self. By means of the things with which a person surrounds themselves, conclusions can be drawn about them by observers. This happens constantly and partly unconsciously, yet another part is individually controlled and even staged by the person being observed. This makes it possible to draw conclusions about the person to be observed, because different worlds of things are associated with sex or gender, age, social class, level of education or socialisation and geographical allocation; one can express oneself with things without words or explanations and communicate one's interests, vocations, tastes and preferences. Furthermore, things are charged with meanings, either by collectives like society or individuals.

Today, there is a strong interest in things that are not essential for life and survival. First the basic needs have to be fulfilled, then the desire is awakened by a large variety of products. These objects, such as high-quality second homes, televisionsets, stereo systems, kitchen appliances, books, etc. are strongly advertised and awakene interest, one feels the need to own them and one accumulates a multitude of things. Consequently, each person now owns an average of 10,000 things. Given this multiplicity of things, the owners might not even remember all the objects they own, but they tend to feel anxiety or even grief when faced with possible or actual losses.

These objects obtain a symbolic charge, which itself has a higher value than the pure utility or material value of the object and generates prestige. These status symbols support their owners, placing them on a supposedly higher level and thus distinguishing them from others. Which objects serve as status symbols and which things are allowed to be owned at all is determined by each culture and community itself in a continuous and ever changing process .

What is special about "my" object?

Today, most things are subject to a thorough individual examination of the desired object even before they are purchased. Because of the multitude of "same" things, a thing, a brand associated with it, has to be chosen among all others according to their advantages and disadvantages. This decision, especially in the case of more expensive objects, may imply committing oneself to one and the same thing for years to come and to share a life with it. In the case of items that are less expensive or even called fashion items, spontaneous purchases are more common.

Whereas in earlier times the things needed for living were handmade and only the rich could afford additional (luxury) items, the industrialisation made consumer goods accessible and affordable to a wider range of people. The mass production of goods and their prefabricated items, however, left little room for people’s individual expression of their personality. This is changing in recent times, many large manufacturers have switched to having parts of their production or constituent parts of an object individually designed by the customer, who can choose from a large variety of shapes, colours, materials and the like. Custom-made items from artisans and designers form another pruchase option for customers, but they are more expensive than individualized mass products such as sneakers.

Most people like to touch things and stroke their surfaces or take them in their hands, react to the smell of the thing, to its colours, its weight and, of course, to possible functions. When designing things, these aspects are taken into account and adapted to the intended user group.

The exhibition Liebes Ding – Object Love

The interesting and extensive exhibition in Morsbroich presenting the works of 23 international artists questions the intimate relationship between people and their things. Objects are shown through photographs and videos, as paintings, sculptures and installations in the following four areas:

- Body and things - an intimate relationship

- Why do we love things? Out of which needs?

- The technological revolution: objects are becoming increasingly intelligent

- The emergence of the consumer society: The ballast of things

2012–2016, Courtesy the Artist; © Kathrin Ahäuser

The first area, about the intimate relationship with objects, is about love for things. This area shows the real love for things by their owners. This can be a simple passion for the beloved thing, when something is "looked at" with love. The work of Katharina Anhäuser, for example, Valentina and Valentino (2012-2016), which shows the owners and their beloved things, documents objectophilia; this means to enter a serious relationship with a thing. Generally speaking, every person has a certain inclination towards it. However, some people live this form of love with all its aspects. These people always want to carry their loved objects with them or have them around and they might fall into mourning if they have to leave their object. These things subsitute a real partner for these people, they communicate with them, hug them, some marry their objects like Tracey Emin. Anhäuser documents here an area of existence that in our ever-growing world of objects is becoming more and more important to many people, even though most people rule out marriage or sexual relations with an object for themselves.

If we look at the work Freudsche Rektifizierung (Freudian Rectification, 2014) by Erwin Wurm, it becomes clear that things also determine our everyday life. With his instructions, the artist confronts the viewer with the task to acti in a certain, determined way with objects from our daily life. However, the instructions counteract and destroy the original use of the item. It is difficult to use the object in the way the artist intended and to remain in the required position, even if only for a short time. This process breaks up the traditional concept of sculpture, broadens it and implements a critique of our love for things and the artist’s handling of them. It also critiques of the effects of consumption, of having to have more and more, and of the associated negative effects of items that have become unusable or are no longer wanted and are discarded as (plastic) waste.

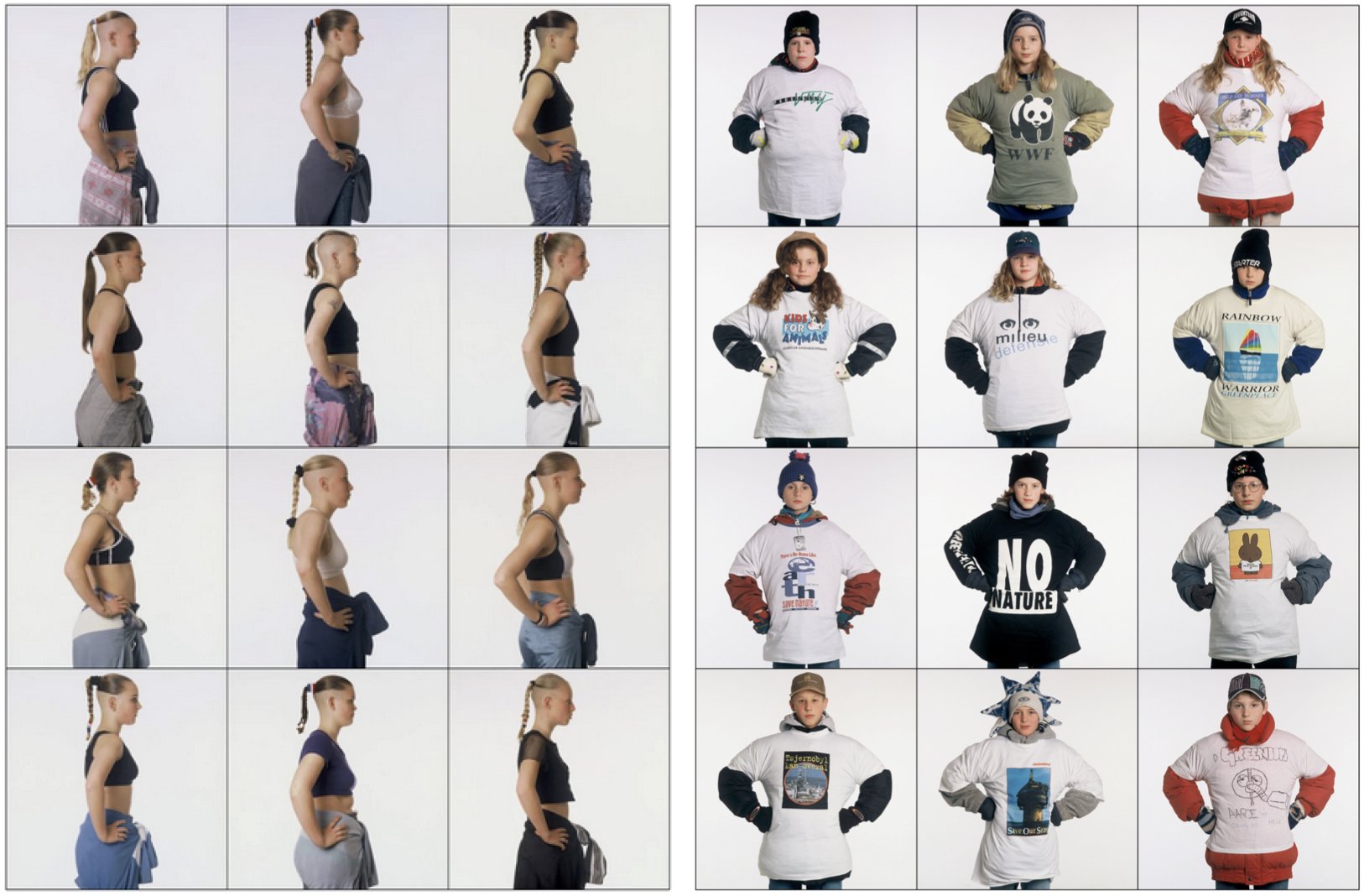

Ari Versluis & Ellie Uyttenbroek, on the left: Gabberbitches – Rotterdam 1996, on the right: Young Activists – Rotterdam 1997, both from the series Exactitudes (from 1994), each 12 Photos C-Prints, framed 100 x 135 cm. Courtesy the artists; © Ari Versluis & Ellie Uyttenbroek

The second area of the exhibition deals with the question of why people love things. In this area, the artist duo Ari Versluis & Ellie Uyttenbroek addresses clothing as a statement and status symbol. With Exactitudes (from 1994), the artists document the demarcation from others and also a desire to belong to a certain group or social class. This differentiation through clothing contributes to the recognition of a certain class or group and serves its "survival". The serially arranged photographs document a social stratum at a certain place and time. Though, in the pictures, everyone belongs to a single stratum and wears the appropriate style of clothing, subtle differences can be detected in the individuals and their clothing. This series of photographs, which has been continued for a long time, is based on August Sander's large-scale series "People of the 20th century". In contrast to Sander, however, the differences among the individual members of a group are documented here and made visible to the viewer.

Courtesy the artist; © Jeroen van Loon; Photo: Hanneke Wetzer

In the field of the technological revolution, the main focus of the discussion is the progress that objects are making in the present day. In his work Life Needs Internet (2017), Jerome van Loon treats the Internet as a thing. He concludes that people of today highly depend on the availability of the Internet. For people, the Internet is a commodity, a thing that contains information, enables communication, is used for work, leisure, love life and self-expression. With his work, the artist also shows the negative sides of internet consumption and speaks not only of leaving personal traces online but also of the dependence of humans on this infrastructure, which in case of a power failure or a cyber attack can throw humans back into the "stone age". Furthermore, there is the possibility that data can be irreparably lost. There is the possibility that the smart things can communicate with each other and in a further step can slowly become detached from people and their actual purpose of use. The work of van Loon thus thematises the fascination of people for the world of "Internet" in its entirety, but also criticizes the inexperienced approach and unquestioning use of it.

Melanie Bonajo, Furniture Bondage (Janneke),

2007, C-Print, 149 x 120 cm, Courtesy the

artist and AKINCI; © Melanie Bonajo

The fourth section of the exhibition addresses the accumulation of things and the ballast of things. The works Furniture Bondage (2007) by Melanie Bonajo are about the masses of things that influence and shape us and our lives. They solely display women tied up by their household appliances, often they can't even get up from a stooped position. The photographic work thus shows the time that we generally devote to things in general when tidying and rearranging. The time spent using and cleaning the same objects, such as plates, is also addressed. At the same time, the work contains a feminist component, since househould and taking care of the things at home is often still largely comes down to women. The artist comes to the conclusion that things also have a given potential to dominate people, that things have to be taken care of, looked after and that every possession also means responsibility. The work shows a clear critique of mass consumption and reflects a living space that, alienated from nature, is made up of nothing but things.

In the large-format photographs Prada I, Prada II (1996, 1997) by Andreas Gursky, luxury consumption is the central theme. The owners of limited and expensive objects, such as the shoes shown here on the shelves of Prada stores, want to set themselves apart from the masses and thus display their wealth in order to rise up in the social order. With his work, the artist criticizes the fact that ever more sophisticated marketing strategies are creating ever new needs among customers. For this reason more and more products are being manufactured that then have to be sold. In this way, the exploitation of resources and labour is pushed forward. The "shrine of consumerism ", which Gursky represents here, thus reflects the consumption of luxury articles and what is hidden behind the beautiful appearance of (luxury) consumption and the world of things.

The exhibition Liebes Ding – Object Love reflects the entire cosmos of the world of things as well as the motives for users and owners to desire and want things. The presented artistic approaches thematise different relationships with things, from the (sexual) love for objects to loving things in general, the technical progress of things and the ballast caused by things. Furthermore, critical and negative aspects of excessive (mass) consumption are addressed and clarified. The catalogue of the exhibition contains, apart from the introduction, a short history of consumerism and things. It also presents the artists’ motives and their statements on their works. It is worth a look and reading! Because everyone discovers a part of themselves in the interesting exhibition on this contemporary theme - after all, each of us calls (too?) many things their own.

The exhibition "Liebes Ding - Object Love" at the Museum Morsbroich in Leverkusen is currently closed. For further information please visit the website of the museum. The interesting and extensive expo was curated by Fritz Emslander and sculpture network coordinator Anne Berk.

The catalogue LIEBES DING can be ordered online from Verlag für Moderne Kunst.

Participating artists:

Kathrin Ahäuser (DE), Thomas Bayrle (DE), Melanie Bonajo (NL), Karsten Bott (DE), Machiel Braaksma (NL), Anton Cotteleer (BE), Danielle Dean (UK/US), Yvonne Dröge Wendel (NL), Maarten Vanden Eynde (BE), Dimitar Genchev (BG/NL), Andreas Gurksy (DE), Ni Haifeng (CN/NL), Jeroen van Loon (NL), Vika Mitrichenko (BR/NL), Olaf Mooij (NL), Ted Noten (NL), Min Oh (KR/NL), Erwin Olaf (NL), Maria Roosen (NL), Superflex (DK), Ari Versluis & Ellie Uyttenbroek (NL) and Erwin Wurm (AT)

Author: Dr. Eva Daxl

Eva Daxl studied art with a focus on sculpture. In her PhD thesis she wrote about ceramic materials in art criticism. She is therefore familiar with three-dimensional works of art in theory and practice.

Title: Melanie Bonajo, Furniture Bondage (Hanna), 2007, C-Print, 149 x 120 cm, Courtesy the artist and AKINCI; © Melanie Bonajo