Moderne und zeitgenössische Adaptionen der Ready-made-Strategie im Bereich bildhauerischer Praktiken am „Rande“ Europas

Bei einigen von Ihnen wird dieser Artikel Fragen aufwerfen (Was genau versteht man unter „Ready-made-Strategien“?) oder, wegen seiner negativen bzw. mindestens fragwürdigen Konnotationen, sogar Empörung über den Begriff „am Rande Europas“ auslösen. Hoffentlich ist das Wort „zeitgenössisch“ das am wenigsten zweideutige. Und was hat es mit den „bildhauerischen Praktiken“ auf sich? Ist das nicht ein sehr vager Begriff? Warum nicht einfach Bildhauerei sagen? Vielleicht ist es daher am besten der Reihe nach darzulegen, was mit jedem dieser Begriffe – im Rahmen dieses Textes – gemeint ist. Anschließend kann das Hauptthema dargelegt werden: die Art und Weise wie Künstler ihr Schaffen verändern, indem sie sich Elemente der Vergangenheit borgen und ihr neu erlangtes Wissen dafür verwenden, die zeitgenössischen (künstlerischen, sozialen, politischen etc.) Bedürfnisse in ihr Werk zu integrieren.

Der Begriff des Randes ist einer der zunächst etwas mehr Beachtung benötigt, da er den geographisch notwendigen Kontext erläutert. Was hier unter „Rand“ zu verstehen ist, sind Räume am äußeren Bereich gewisser kultureller und künstlerischer Modeerscheinungen – denn für gewisse Phänomene braucht es aus verschiedenen Gründen etwas länger um „anzukommen“. Es ist wichtig festzuhalten, dass dieser Begriff hier keinesfalls abwertend gemeint ist, sondern eher ein geographischer Marker und ein Beschreibungselement ist. Geographisch gesprochen handelt es sich bei den hier benannten Rändern um die Balkan- Halbinsel, oder, konkreter gesagt, um das heutige Kroatien. Der Beitritt Kroatiens zur Europäischen Union im Jahr 2013 fungierte gewissermaßen als Ausschlusskriterium von dem, was missverständlich oft in einem kulturellen Sinne als „die Balkanstaaten“ bezeichnet wird. In diesem Text soll nicht der Frage nachgegangen werden, ob Kroatien geographisch oder kulturell zum Balkan gehört, denn dies ist ein unerschöpfliches Thema. Mitunter wird das Land als Teil Zentraleuropas oder sogar Osteuropas bezeichnet. Nichtsdestotrotz ist es, historisch betrachtet, eine Region, deren Künstler bisher kaum als Trendsetter wahrgenommen wurden, sondern eher als Region, die den Trends der sogenannten kulturellen Zentren wie Prag, Wien, München, Paris und New York folgt. Dies geschieht durch Bildung, Reisen und Ausstellungen im Ausland. Damit soll nicht gesagt werden, dass kroatische Künstler isoliert oder nicht aktuell oder stark konventionell arbeiten würden. Im Gegenteil, viele Künstler und Künstlergruppen, die hauptsächlich in der Landeshauptstadt Zagreb angesiedelt sind, zeigten starke Tendenzen hin zur Avantgarde, die im Einklang mit europäischen und sogar weltweiten Praktiken lagen. All dies brauchte nur etwas mehr Zeit als in den sogenannten Zentren. Dieses Phänomen wurde von kroatischen Kunsthistorikern wie Ješa Denegri beobachtet, der den Begriff „randständig“ als einen selbstkritischen oder sogar selbstbemitleidenden Begriff erkannte, der daher in Frage gestellt werden sollte. Er hielt fest: „Ein Bereich, der ein solch kulturelles Zentrum (wie Zagreb) hatte, das in der Lage war Ströme an radikalen künstlerischen Standpunkten zu formen und enge Verbindungen mit Europa aufrecht zu erhalten, das ähnliche künstlerische Bestrebungen zeigt, sollte, der Selbstidentifikation wegen, keine Begriffe wie den der „Randstruktur“ verwenden; er sollte nicht weiter nach Alibis Ausschau halten, durch die er sich selbst an eine örtliche Umgebung bindet. Gewiss, Kunst kann in jedem Milieu auf verschiedene Weise ins Leben gerufen werden, aber dem liegt ein gemeinsamer, drängender Anspruch zugrunde: man muss am großen, weltweiten Austausch künstlerischer Ideen und Probleme teilnehmen, man muss auf der Bühne stehen, auf der weltweite künstlerische Prozesse während verschiedener historischer Momente stattfinden.“ Ein weiterer bedeutender kroatischer Kunsthistoriker, der sich mit Themen rund um „den Rand“ befasste, war Dr. Ljubo Karaman. Sein Fokus lag jedoch auf den sich stark unterscheidenden Kontexten der mittelalterlichen Architektur und der Architektur der Renaissance sowie der architektonischen Dekoration Kroatiens. Er unterscheidet zwischen provinzieller Kunst, Kunst marginalisierter Bereiche und Kunst der Randbereiche. Er unterscheidet zwischen diesen Begriffen, hält aber auch fest, dass es wichtig ist, ihnen kritisch und flexibel gegenüberzutreten. Kurz gesagt, all diese Begriffe sind bis zu einem gewissen Grad geographisch. Provinzielle Kunst ist jedoch Kunst, die hauptsächlich leiht und/oder einzig von einem Bereich inspiriert ist (und häufig überschattet wird, was an der oft einfachen sozialen und wirtschaftlichen Situation des Bereichs liegt). Auf der anderen Seite leihen marginalisierte Bereiche ihre Inspirationen von verschiedenen, sich stark unterscheidenden Orten. Dies führt zu neuen Kunstformen, ohne jedoch die Einflüsse unsichtbar zu machen. Kunst der Randgebiete ist, auf eine Art, die höchst entwickelte Kunstform der drei, weil sie eklektisch ist (sie leiht gleichzeitig von vielen verschiedenen Zentren und Zeitstufen) und sie durch ein Maß an freier Ausdruckskraft gekennzeichnet wird, was sich daran zeigt, dass sich das umformt, was sie geliehen hat und so eine andere und individuelle Form der Ausdrucksweise ermöglicht wird (Karaman 6-8). Alles in allem geht der Begriff des „Randes“ im Titel dieses Artikels mit Karamans Verständnis des Begriffs konform, denn, wie gezeigt werden wird, moderne und zeitgenössische kroatische Künstler nutzen eklektisch was sie benötigen, unabhängig von geographischen oder zeitlichen Grenzen.

Dieser Übergang von Ideen und künstlerischen Praktiken umfasst auch eine große Spanne bildhauerischer Praktiken. Die Verwendung des Begriffes „bildhauerischer Praktiken“ ist in diesem Fall eine Frage der Genauigkeit. Es sei klärend erwähnt, dass man im Bereich moderner und zeitgenössischer Bildhauerei die Verwendung verschiedener, mit einander konkurrierender Begriffe in Bezug auf dreidimensionale künstlerische Praktiken finden kann (neben Architektur) – Bildhauerei, bildhauerische Praktiken, Objekte, Strukturen oder einfach dreidimensionale Werke. Dies verweist auf das Problem terminologischer Ungenauigkeit, die tatsächlich ein wesentlicher Bestandteil moderner und zeitgenössischer kultureller Praktiken ist. Der Begriff „bildhauerische Praktiken“ wird hier verwendet um zu zeigen, dass zeitgenössische Bildhauerei nicht immer traditionelle bildhauerische Mittel nutzt und daher verschiedene Formen annehmen kann. Allgemein gesagt, jegliche dreidimensionale Kunst fällt nun in die Kategorie der Bildhauerei (entweder in diese, oder in den Bereich der Architektur). Viele von ihnen sind zeitlich begrenzt (Performances etc.), vergänglich (diejenigen, die ätzende und natürliche Materialen verwenden), konzeptuell oder vielleicht „de-materiell“, um Lucy Lippards Begriff zu verwenden. Sicher, an irgendeinem Punkt im Laufe der Geschichte verwandelte sich Bildhauerei in bildhauerische Praxis, um so den Kanon künstlerischer Werke zu weiten. Warum auch nicht? Kulturen und Gesellschaften verändern sich, die Umwelt und Kontexte verändern sich. Es ist daher nur folgerichtig und sollte als natürlich angesehen werden, dass sich die Bildhauerei auch verändert.

Eine spezifische Veränderung der Bildhauerei im Besonderen ist hier interessant – die, die als ready-made bezeichnet wird. Der Begriff geht auf Marcel Duchamp und das Jahr 1915 zurück, auch wenn er das erste ready-made bereits zwei Jahre vorher vollendete. Interessanterweise gab er in Interviews zu, dass er es nie geschafft hatte, seine bildhauerischen Figuren einer Definition zu unterziehen. Aber wir wurden dankenswerterweise von seinem Zeitgenossen André Breton mit einer ausgestattet, der ready-made als „ein gewöhnlicher Gegenstand, der einfach durch die Wahl des Künstlers mit der Würde eines Kunstobjekts versehen wird“ (de Duve 92) bezeichnete. Die Art wie Duchamp Skulpturen an seine Zeit und seinen Ort anpasste, war dergestalt, dass er versuchte, das was er als „die Netzhaut betreffend“ bezeichnete, auszulöschen versuchte. (Die Netzhaut betreffende Kunst hat nur den Nutzen optisch anzusprechen; er legte den Fokus auf den intellektuellen Aspekt von Kunst.) Daher waren die Objekte, die er auf das Podest der Kunst erhob (sowohl metaphorisch als auch wörtlich, wie sein berüchtigter Fountain aus dem Jahr 1917 zeigt), nicht dafür gedacht, dem Auge zu gefallen, sie sollten „narkotisierend“ (Duchamps Wortwahl) sein. Der Künstler und der Betrachter sollten dem Objekt gleichermaßen neutral gegenüberstehen. Die ready-mades waren Gegenständer, aber ihre Gegenständlichkeit war der am wenigsten wichtige Aspekt ihres Wesens. Im Grunde wurden sie dafür geschaffen, das System, das wir Kunst nennen (das Arthur C. Danot und George Dickie die Kunstwelt nennen) zu testen und unsere Vorstellung von Kunst, Künstlern, Kreativität, Originalität und Ernsthaftigkeit in der Kunst herauszufordern. Sie waren bis ins Mark intellektuell und sollten konzeptuell verstanden werden (es ist klar wohin dieser Wege einige Jahre später führte). Daher waren die ready-mades, gemäß Durchamp, eine fade Kunstform, die verzweifelt einer Neuzusammenstellung bedurfte, wenn sie den aufwühlenden Zeiten der Epoche gerecht werden wollte. Wie die Dadaisten, Futuristen und später Surrealisten sowie sogar Kubisten (ihnen allen kann Duchamp mehr oder weniger zugeordnet werden) zeigten, war eine Gesellschaft, die durch Krieg(e) erschüttert worden war, auf neue Formen von Kunst angewiesen; auf Formen, die ebenso verstörend und provokant sind.

Natürlich soll das Hauptaugenmerk dieses Artikels auf der Bildhauerei liegen, vor allem auf der zeitgenössischer Künstler (d.h. auf den noch lebenden oder, in wenigen Fällen, kürzlich verstorbenen), die sich auf ihre modernen Vorgänger (v.a. Duchamp) beziehen, ohne die einige „bildhauerische Praktiken“ unvorstellbar wären oder erst viel später möglich gewesen wären. Als Ausschlusserklärung ist festzuhalten, dass dieser Text eine etwas weite Zeitspanne umfasst, um so einen breiteren und leichter verständlichen Kontext zu erhalten, in dem der Ursache-Wirkung Strom der Ereignisse dargestellt wird, der zu dem Auffinden von ready-made in Kroatien geführt hat.

Einige Kunstwerke wären vermutlich Totgeburten gewesen, wären sie nicht zu jener bestimmten Zeit erschaffen worden, für jene spezifische Zuschauerschaft. Sie hätten ihre Botschaft nicht vollständig und adäquat übermitteln können. Nachdem dies festgehalten wurde, ist es auch sinnvoll, die weisen Worte Peter Burgers zu bedenken, die aus seinem kanonischen Werk Theory of the Avant-Garde stammen: „Obwohl Kunstformen ihre Geburt einem bestimmten sozialen Kontext verdanken, sind sie nicht an diesen oder eine ähnliche soziale Situation gebunden, denn die Wahrheit ist, dass sie verschiedene Funktionen in unterschiedlichen Kontexten einnehmen können.“ (69). Dies kann im Laufe der Zeit und über Orte hinweg geschehen, wie Bernice Murphy in ihrem Text Marcel Who? (The Readymade in the Context of the Province erläuterte: „Zu dem Zeitpunkt, zu dem Readymade im Sinne Duchamps in der Provinz ankommt, ist seine Bedeutung bereits durch die Veränderungseffekte der Reise vom Zentrum ausgehend gewandelt. Marcels Flaschengestell […] wäre bereits ein sehr exotisches und merkwürdiges Objekt zu dem Zeitpunkt, zu dem es seinen Weg in ein Pariser Küchengeschäft gefunden hätte […]“ (112). Zudem erklärt sie, dass die Vorstellung eines „ursprünglichen Kunstwerks“ (wie relativ das auch in Bezug auf ready-made sein mag) in den Metropolen viel mehr Bedeutung trägt. Die Provinz hingegen kommt selten mit Originalen, sondern eher mit Kopien von Kunstwerken in Kontakt, sei es durch physische Reproduktionen oder durch photographische. (Murphy 117). Kroatien war da keine Ausnahme.

Wenn es um internationale Beziehungen und Neuigkeiten im Bereich globaler/europäischer Praktiken ging, waren kroatische Künstler gut verknüpft und informiert (einige waren auch extrem versiert auf dem Bereich der Kunsttheorie). Dennoch kam das Konzept des ready-made in Kroatien erst in den 1960er Jahren durch das Werk der Gorgona Gruppe an. Sie gilt als ein Vorläufer der konzeptuellen kroatischen Kunst. Davor wendeten kroatische (oder eher: jugoslawische) Künstler seit den 1920er Jahren gewisse Aneignungsstragien an, indem sie Collagen und Sammlungen schufen, in die sie gelegentlich gefundene Objekte oder weggeworfene Materialien einfügten. (Denjenigen, die mehr zu dem Thema wissen wollen, seien die Werke von Josip Seissel, bekannt als Jo Klek, oder Antun Motika empfohlen.) Jedoch war Duchamps direkter Einfluss erst dann ersichtlich, als die Grogona Gruppe von Freunden und Korrespondenten aus Paris von ihm und seinen Ideen erfuhr. Gewiss, die künstlerischen Tätigkeiten der Gruppe wurden vor allem im Privaten ausgeführt, daher hatte die Idee des ready-made kaum eine Chance sich auszubreiten. Dennoch wurden ihre Kunstwerke in den späten 1970er Jahren „wiederentdeckt“ und einer breiteren Öffentlichkeit in einer Retrospektive 1977 in der Galerie für zeitgenössische Kunst in Zagreb zugänglich gemacht. Eine Welle der Ankerkennung folgte und die Mitglieder wurden als Wegbereiter der konzeptuellen Kunst gefeiert, was am Fokus ihrer Arbeit auf der Idee, die hinter dem Kunstwerk liegt, der De-Materialisierung des Kunstwerks, der Verwendung von Absurdität und zweideutigen Spielereien und der Reduktion der Rolle des Ästhetischen, lag. (All dies waren auch Prinzipien Duchamps.) Es ist wichtig festzuhalten, dass viele der Werke, die mit dem Konzept des ready-made in Verbindung gebracht werden und die von der Gorgona Gruppe erschaffen wurden, nicht zwangsläufig ready-made (Gegenstände, die einfach genommen werden, mit nur geringem oder keinem Aufwand vom Künstler) waren. Viele von ihnen waren „assisted ready-mades“ (eines oder mehrere ready-made Gegenstände, die zu einer neuen Form kombiniert werden und so ein neuer Gegenstand werden, in dem der Künstler nach wie vor kaum seine persönliche Note einbringt, um so die Botschaft zu erhalten). Das in diesem Kontext berühmteste Beispiel jener Zeit und jenes Ortes muss ein assisted ready-made sein, das damals einfach als Installation bezeichnet wurde. Es stammt von Josip Vaništa, einem Mitglied der Gorgona Gruppe, der gleichzeitig als modern und zeitgenössisch bezeichnet werden kann (er verstarb erst kürzlich, Anfang 2018). Das fragliche Werk trägt den Titel Infinite Cane - Homage to Manet und stammt aus dem Jahr 1961 (Bild 1). Es besteht aus einem Sessel und einem Hut (beides erhielt der Künstler von Ortsansässigen mittels einer Anzeige in der Zeitung) und einem gedoppelten und daher nutzlosen Gehstock, den der Künstler gemäß seiner Vorstellung und extra für die Installation machen ließ. Natürlich gibt es noch viele weitere Beispiele, sowohl von Vaništa als auch von verschiedenen anderen Mitgliedern der Gorgona Gruppe, aber die Zeitleiste, ebenso wie dieser Artikel, muss weitergehen.

Josip Vaništa, Infinite Cane - Homage to Manet,87 x 112 x 50 cm (1961)

Copyright: Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb (Muzej suvremene umjetnosti Zagreb), photo by Boris Cvjetanović. Photo source: Documentation and Information Department of the Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb

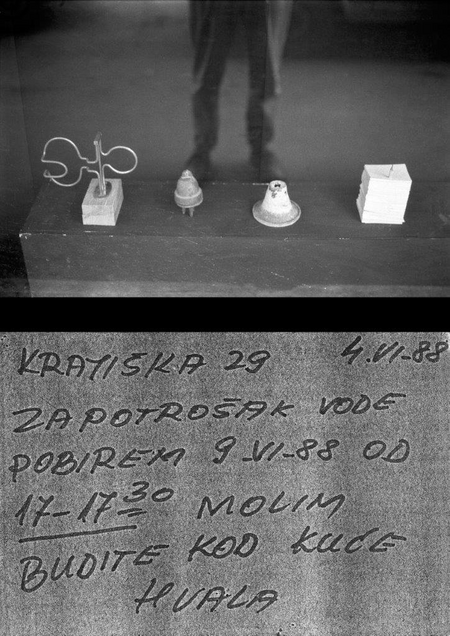

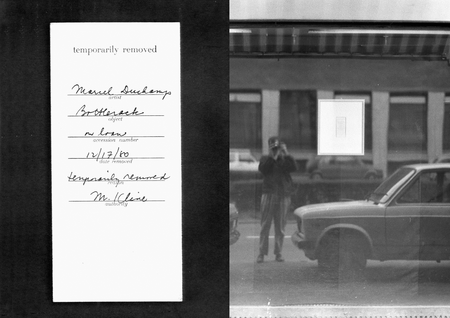

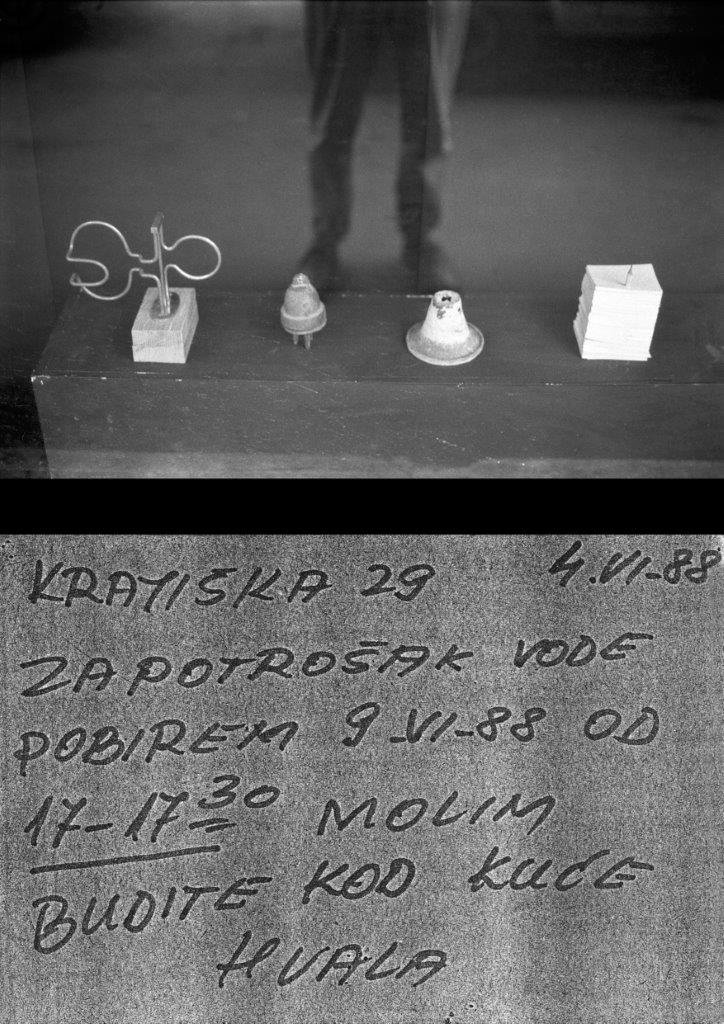

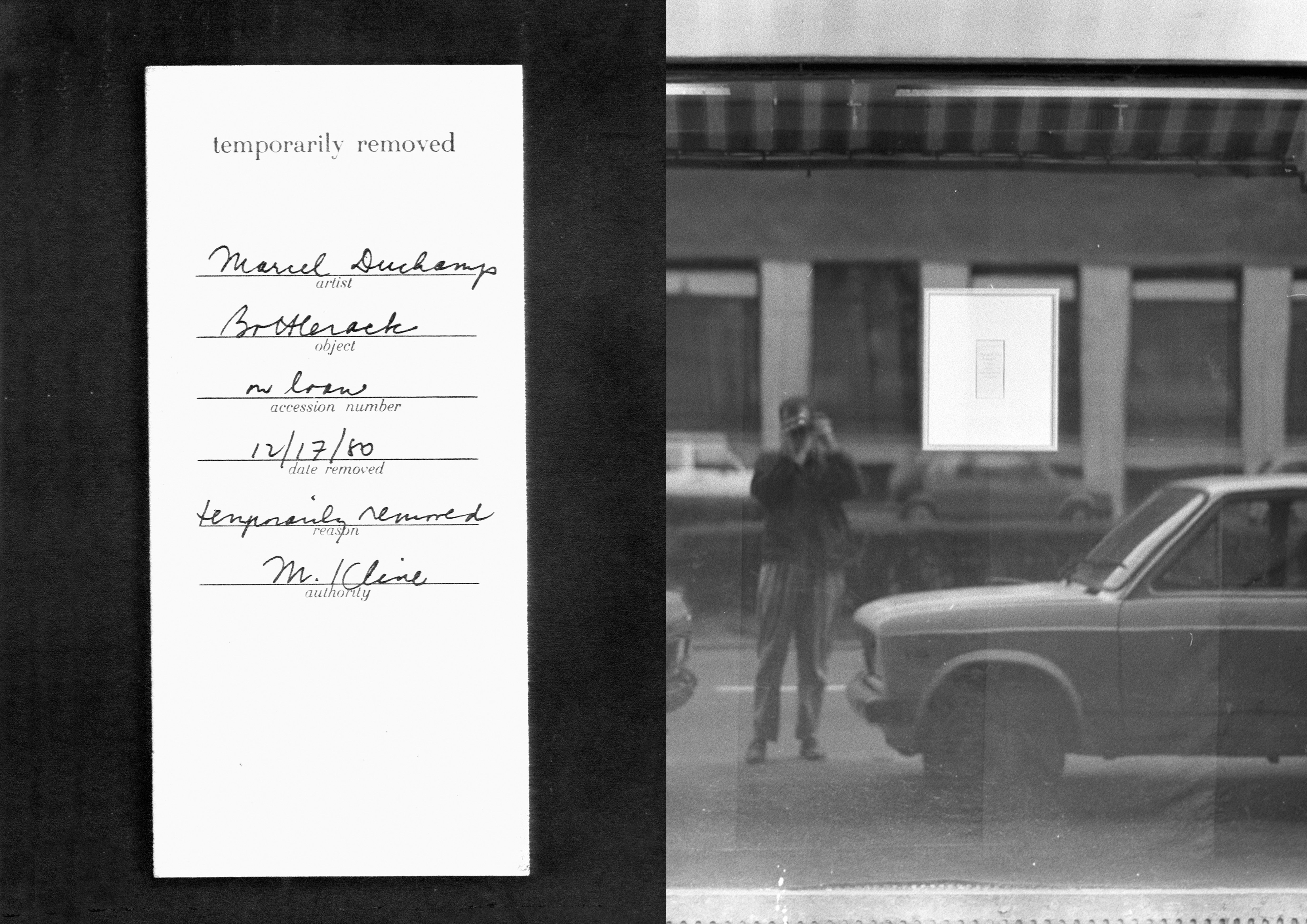

Nach der oben genannten Retrospektive entschieden sich jüngere Künstler sich mehr mit der Idee des ready-made auseinanderzusetzen (viele von ihnen werden nun der New Art Practice zugeordnet, die in den späten 1960er Jahren aufkam und die gesamten 1970er Jahr in Jugoslawien andauerte). Dies fiel mit der Veröffentlichung eines Bändchens des Museums für zeitgenössische Kunst in Belgrad zusammen (1984) – dies stellt die erste Übersetzung von Duchamps Text ins jugoslawische dar. Unter diesen Texten war auch der kanonische „Apropros of readymades“ (Gavrić 47), der ab da für jugoslawische Künstler und die breite Öffentlichkeit zugänglich war. Im Februar und März desselben Jahres wurde Duchamps La boite en valise im Museum für zeitgenössische Kunst in Zagreb präsentiert (Katalog 716). Dies war an sich ein bedeutender Moment in dieser Chronologie wichtiger Ereignisse, denn Duchamp konnte erstmals von kroatischen Künstlern und Kunstinteressierten betrachtet werden. Schon 1988 nahm eine Ausstellung den Begriff „ready-made“ in ihren Titel auf. Sie war in einem Schaufenster eines Zagreber Buchladens zu sehen (Bilder 2-4). Die Ausstellung wurde vom Photographen Žarko Vijatović organisiert, dokumentiert und kuratiert. Das eher improvisiert anmutende Heftchen, das die Ausstellung begleitete, beinhaltete dieselbe Übersetzung von „Apropos of readymades“ des schon genannten Bändchens des Zagreber Museums für zeitgenössische Kunst. Auf dieses wird auch Bezug genommen, was zeigt wie gut örtliche Künstler und Kunsthistoriker zu diesem Zeitpunkt mit Duchamps künstlerischer Philosophie vertraut waren. Das Heftchen wurde nur an die Künstler der Ausstellung ausgegeben – es handelte sich um eine Sammlung kopierter Photographien der Werke, die „Apropos of readymades“ vorangingen sowie eines Zeitungsartikels, der die Ausstellung nennt (in einem Interview mit Herrn Vijatović); nur ein Absatz stammt vom Kurator selbst. Indem Vijatović einen „Ausstellungskatalog“ herstellte, der fast zur Gänze unoriginell war, bezog er sich auf Walter Benjamins Idee des „Verlusts der Aura“ von Kunstwerken durch Reproduzierbarkeit (diese Idee war der Gorgona Gruppe und den Künstlern der Zeit bekannt).

Tatsächlich bestand die Ausstellung von 1988, die „Ready-Mades“ hießt aus neun konsekutiven, bescheidenen Einzelausstellungen verschiedener Künstler. Einer von ihnen war, das dürfte nicht überraschen, Josip Vaništa. Zwei seiner Gorgona Freunde nahmen auch teil (Dimitrije Bašičević, bekannt als Mangelos und Julije Knifer). Es waren aber auch jüngere Künstler beteiligt und es ist dank ihnen und ihrer Einflüsse, dass die ready-made Strategie in den 1990er und 2000er Jahren blühen konnte. Die Namen, deren Nennung sich die Autorin verpflichtet fühlt, sind Tomislav Gotovac, Vlado Martek und Goran Trbuljak. Tomislav Gotovac stellte einige objets trouvés aus, die er einfach am Straßenrand fand und mitnahm sowie eine handschriftliche Bekanntmachung aus seinem Mietshaus, die auf ein Treffen der Mieter aufmerksam machte, was er der Ausstellung gemäß fand (Bild 2). Vlado Market stellte eine Flasche und ein leeres Glas, sowie einen Zettel mit Gedichten aus, die sich dem Genuss von Alkohol widmeten. Er modifizierte sie, in dem er über sie drüberschrieb (Bild 3). Goran Trbuljaks Werk (Bild 4) ist für den aktuellen Kontext sehr wichtig, da es in der Ausstellung „The art of appropriation“ der Forum Gallery Zagrebs im Jahr 2017 erneut ausgestellt wurde. Es bestand einzig aus einem Schildchen, das aus dem Philadelphia Museum of Art „geborgt“ (d.h. gestohlen) und anschließend gerahmt worden war. Es besagte, dass Duchamps Bottlerack „für den Moment entfernt“ worden war. Die Idee hinter diesem Werk ist einfach – das Schildchen, das das Kunstwerk ersetzte, entspricht dem Kunstwerk selbst (Ready-Mades 21). Es wird allein daran deutlich, wie nah Trbuljak an konzeptueller Kunst ist.

Tomislav Gotovac, unknown (ready-mades exhibited in the shop window of the bookstore Znanje-August Šenoa in Zagreb) (1980-1990)

Copyright: Žarko Vijatović. Photo source: private photo collection of Žarko Vijatović

Trbuljak und Martek sind noch am Leben und wohlauf, wohingegen Vaništa dieses Jahr verstarb und Gotovac 2010 verstarb. Es muss betont werden, dass sich das Werk von Vaništa und Gotovac als extrem einflussreich für die jüngere Künstlergeneration, mit denen sie Ideen austauschten, herausstellen sollte. (Vaništa unterrichtete sogar einige von ihnen, darunter auch Gotovac). Gotovac beispielsweise setzte seine Idee der ready-mades fort, dadurch dass er ab 2010 „ready-made movies“ machte. Jeder Film besteht aus einer längeren Sequenz, die er einem anderen Film entnahm sowie aus einer ersten Einstellung mit dem Titel und dem Namen des Autoren des Films – Tomislav Gotovac (Šimičić 8f.) Vaništa nutze in seiner Kunst auch weiter Aneigungsstrategien, oder Prinzipien, die denen Duchamps ähneln, wie z.B. die Aneignung und das wiederholte Zeigen des Gemäldes der Mona Lisa in der sechsten Ausgabe des Gorgona-Magazins (was seine Kenntnisnahme der Ideen Walter Benjamins beweist, die in dessen Werk Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit dargelegt werden). Auch verwendete er Photos, die andere gemacht hatten und bearbeitete sie nur leicht, um „Porträts“ der Mitglieder der Gruppe herzustellen. Trbuljka setze sein Werk in der konzeptuellen Sphäre fort und erschuf nicht per se ready-mades, obwohl er weiterhin die Rolle des Künstlers als Erschaffers infrage stellte, ebenso wie Institutionen im Bereich der Kunst und allgemein die Idee von Kunst. Er kam jedoch nah daran, mehr ready-mades mit seinen „photographischen Installationen“ zu schaffen, sie hießen Psycho-Installations und sind aus dem Jahr 1993, in dem er alltägliche Gegenstände, die er nicht mehr behalten wollte (wie alte Radios, Waagen und allgemein Haushaltsgegenstände) nahm und verknüpfte. Er photographierte sie, um ihre Erinnerung zu bewahren, bevor er sie entsorgte (Stipančić 123-124). Dies war eine interessante Kombination aus Photographie, assisted ready-mades (gemäß Duchamps Bicycle Wheel) und eine merkwürdige Art von „rückwärtslaufender“ Müllkunst oder vielleicht tatsächlicher Müllkunst, denn die Gegenstände waren bereits als nutzlos deklariert worden und wurden noch nutzloser als sie ihrer Funktionen im künstlerischen Prozess beraubt wurden. Martek setzte seine Arbeit im konzeptuellen Bereich und der Group of Six Authors in den 1970er und frühen 1980er Jahren fort, bevor er Solokünstler wurde. Sein späteres Werk befasste sich jedoch mehr mit der Integration von Worten und Kunst (er verstand sich eher als Dichter). Die Botschaften hatten oft einen humoristischen Unterton und Wortspiele (ebenso verfuhr Duchamp bei den Inschriften zu seinen ready-mades).

Copyright: Žarko Vijatović, Photo source: private photo collection of Žarko Vijatović

Die ready-made strategy in Kroatien folgte einer Zeitleiste, die der vom Rest Europas glich; sie infiltrierte langsam die konzeptuelle Kunst und bereitete den Weg für Installationen. Die Grenze zwischen Installation und ready-made ist oft schwammig (wie Vaništa’s Infinite Cane zeigt). Dies gilt vor allem, wenn die Installationen kleiner sind und überwiegend oder ausschließlich aus ready-made Gegenständen bestehen, die kombiniert wurden, um ein neues künstlerisches Produkt zu schaffen. Es ist wert, dass dies genannt wird, da die Werke der beiden nun noch aufzugreifenden Künstler oft so bezeichnet wird.

Ein zeitgenössischer Künstler, der eng mit Martek in Verbindung gebracht wird (durch die Group of Six Authors) ist Mladen Stilinović. Während seiner gesamten künstlerischen Laufbahn forderte er die Grenzen von Kunst und sozialen Normen mit seinen Installationen und gelegentlichen Collagen (die an sich schon eine Art künstlerischer ready-made Strategie sind), heraus. Er hat ganze Serien von Werken produziert, die auf Geld basieren und gelegentlich modifiziert sind (Schreiben auf Geld, Schneiden von Geld), oder zu einer größeren räumlichen Installation arrangiert sind. Er nutzt verschiedene Alltagsgegenstände in seinen Installationen wie Brot (wobei es farblich verändert wird) und süße Teilchen, Zuckerpäckchen, Wecker, Kissen, Küchenutensilien (v.a. Teller und Löffel) und so weiter. (Ein umfassendes Portfolio seiner Werke kann auf seiner Website eingesehen werden, die bei den Quellennachweisen dieses Textes zu finden ist.) Natürlich geschah all dies mit Absicht – nicht mit einer künstlerischen Absicht, sondern mit dem Wunsch eine gewisse, oft (un-) politische, kritische, den Zuschauer herausfordernde Botschaft zu senden. Er fuhr damit fort, Marcel Duchamp in drei seiner Werke direkt „zu zitieren“. Sie sind aus den Jahren 2009 und 2011 und wie folgt betitelt: I am Selling M. Duchamp, I am Selling M. Duchamp, H. U. O., H. I. H. I. (das Duchamps L.H.O.O.Q. vom Namen her ähnelt) und nochmals I am Selling M. Duchamp. Jedoch ist keines dieser Werke ein ready-made, da sie vom Künstler geschaffen wurden, der von Hand eben jene Worte auf Stoffreste oder Pappe schrieb. Aber sie stellen dennoch einen Beweis der Bedeutung Duchamps für Martek und das allgemeine künstlerische Klima dar.

Der jüngste Künstler, der hier dargestellt wird, hat keinen direkten Bezug zu den bereits genannten, aber einige seiner Werke (vor allem Installationen) können mit Duchamp in Verbindung gebracht werden. Viktor Popović schuf Installationen von aufeinander gestapelten Stühlen und Argonrohren im Jahr 2006. Die Stühle waren benutzt und zeigten auf ihren hölzernen Sitzflächen Spuren der Abnutzung. Sie wurden für den Zweck der Installation während des Aufenthalt des Künstlers in Portland (USA) geliehen. Wie man es erwartet, wird ein Stuhl nutzlos, wenn man ihn umdreht; sie wurden nutzlos, so wie Duchamps Barhocker in Bicyle Wheel gut ein Jahrhundert davor. Wie Popović erklärte, die Stühle „wurden aus ihrem ursprünglichen Kontext entfernt, so dass eine Nutzung als funktionales Objekt verhindert wurde“. Sie wurden in einen neuen Kontext gestellt, einen künstlerischen (Popović). Diese Beschreibung liegt gefährliche nahe an Bretons Definition von ready-made.

Eine weitere Serie an Werken, bei denen die Autorin nicht umhinkommt sie mit Duchamp in Verbindung zu bringen, stammt aus dem Jahr 2007. Die Installationen (Bilder sind auf der Website des Künstlers, die im Quellennachweis genannt wird, zu finden) bestehen aus geliehenen alltäglichen Gegenständen, die mit einer dicken Gummiunterlage umhüllt sind, damit sie unsichtbar sind, oder der Betrachter sie höchstens vage sieht. Daher sind sie von etwas Geheimnisvollem umgeben. Popović erläutert: „Die ausgewählten Gegenstände, die unter identischen Gummiunterlagen versteckt sind, waren kaum zu sehen, während der Zuschauer, der wusste, dass sie ausgestellte Kunstwerke waren und daher nicht angefasst werden durften, grübeln musste, um was es sich handelt.“ Die wichtige Verbindung zu Duchamp liegt in den ausgestellten (oder eben versteckten) Objekten. Es waren Schreibmaschinen. Duchamp hatte in einem seiner Werke auf Schreibmaschinen Bezug genommen, wobei er eine Strategie anwendete, die der Popovićs gegenüberstand. Während Popović seine Schreibmaschinen unter dicken Gummimatten verbarg, stellte Duchamp die Hülle einer Underwood-Schreibmaschine aus – ohne die Schreibmaschine selbst (Traveller's Folding Item / ...pliant,... de voyage, 1916.)

Goran Trbuljak, Without the knowledge of the museum's administration, alienated information about the loan, thinking it is identical to the original tor which it stands in, 20 x 30 cm, 1981

Copyright: Žarko Vijatović, Photo source: private photo collection of Žarko Vijatović

Marcel Duchamp beeinflusste Generationen von Künstlern in hohem Maße, nicht nur in Jugoslawien (und Kroatien), sondern überall auf der Welt – von Manzoni bis Fontana, Rauschenberg und Johns, Warhol und Ai Weiwie, Sherrie Levine und Jimmie Durham… Die Liste ließe sich endlos fortsetzen. Als Beleg können die Worte Arthur C. Dantos gelten: „Marcel Duchamp wird von Jean Clair als ‚primus inter pares‘ betrachtet. Mehr als jeder andere brachte Duchamp das Widerwärtige in die zeitgenössische Kunst, als er versuchte ein Urinal als Ausstellungsstück für die Exhibtion of Indepenent Artists in New York im Jahr 1917 einzureichen. Es war ganz unverkennbar ein Urnial, obwohl es als R. Mutt, 1917 beschriftet war und es hat, weit mehr als Manzonis oder sogar Beuys‘ Werk, einen legendären Status in den Annalen der Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts erreicht.“ Die Auswirkungen dieser Idee waren weitreichend und sprengten alle Grenzen: zeitliche, generationale, geographische und soziale. Wenn Cézanne als Vater der modernen Kunst bezeichnet wird, dann kann Duchamp ohne Weiteres, wenn nicht als Vater der Avantgarde, dann wenigstens als ihr erster Gesandter gelten. Duchamp befreite als Vorreiter der konzeptuellen Kunst und als Niederreißer von Grenzen die dreidimensionale Kunst von ihren körperlichen Grenzen und ermöglichte es kommenden Generationen von Künstlern eine grenzenlose Menge an Material (von denen viele „nicht-künstlerisch“ waren oder gar nicht als Material betrachtet wurden) zu verwenden. Er war seiner Zeit voraus und erkannte die Notwendigkeit einer künstlerischen Ausdrucksweise, die über die Netzhaut hinausgeht und die Synapsen involviert. In unserer modernen konsumorientierten Welt kann der zeitgenössische Kunstbetrachter und Künstler Trost und Ruhe nur in solchen immateriellen Werken finden und durch sie dazu angeregt werden, tatsächlich einmal durch das aktive Interpretieren eines Kunstwerks zu denken. In diesem Zeitalter der Passivität – passive Nutzung der Medien, untätiges Betrachten des Newsfeeds, gedankenloses Einkaufen, vorgefertigtes Essen und Dienste, die all unseren Bedürfnissen gerecht zu werden suchen – ist ein kleines Maß an mentaler Aktivität mehr als willkommen. In gewisser Weise werden diese allgegenwärtigen sozialen Themen von Künstlern aus den „Zentren“ und den „Rändern“ durch die Nutzung künstlerischer ready-made Strategien bekämpft. Gibt es einen besseren Weg den vorherrschenden ready-made Lifestyle, den wir leben, einzudämmen?

Quellennachweis:

1. „Antun Motika,” Avantgarde Museum, February 14, 2017, https://www.avantgarde-museum.com/en/museum/collection/authorsantun-motika~pe4502/

2. Bürger, Peter. Theory of the Avant-Garde, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984.

3. Catalogue of the Collection; Chronology of Exhibitions, ed. Snježana Pintarić, Zagreb: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2008.

4. Danto, Arthur C. "Marcel Duchamp and the End of Taste: A Defense of Contemporary Art," Tout-fait, December 2000., http://www.toutfait.com/issues/issue_3/News/Danto/danto.html

5. De Duve, Thierry. Kant After Duchamp, London: The MIT Press, 1996.

6. Denegri, Ješa. Prilozi za drugu liniju: kronika jednog kritičarskog zalaganja, Zagreb: Horetzky, 2003.

7. Gavrić, Zoran. Marcel Duchamp: izbor tekstova, Beograd: Muzej savremene umetnosti, Beograd, 1984.

8. “Josip Seissel (Jo Klek),” Avantgarde Museum, September 4, 2010, http://www.avantgarde-museum.com/hr/museum/kolekcija/JOSIP-SEISSEL-JO-KLEK~pe4481/

9. Karaman, Ljubo. O djelovanju domaće sredine u umjetnosti hrvatskih krajeva, ed. Milan Prelog, Zagreb: Društvo historičara umjetnosti NRH, 1963.

10. Murphy, Bernice. “Marcel Who? (The Readymade in the Context of the Province),” in: The Readymade Boomerang: Certain Relations in 20th Century Art, ed. Rene Block, Sydney: The Biennale of Sydney, 1990.

11. Popović, Viktor. “Works,” Viktor Popović, August 23, 2017, http://www.viktorpopovic.com/page1/page22/

12. Ready-mades, autorski izlog knjižare Znanje - August Šenoa, ed. Žarko Vijatović, exhibition catalog, Zagreb: 1990.

13. Stilinović, Mladen. “Works,” Mladen Stilinović, October 4, 2013, https://mladenstilinovic.com/works/11-2/

14. Stipančić, Branka. Mišljenje je forma energije: eseji i intervjui iz suvremene hrvatske umjetnosti, Zagreb: Arkzin: Hrvatska sekcija AICA, 2011.

15. Šimičić, Darko. Tom Gotovac / Strategija readymadea, exhibition catalog, Zagreb: Galerija Forum, 2017.

Die Übersetzungen der Zitate stimmen nicht aus den original übersetzen Büchern, sondern von der Übersetzerin des Artikels gemacht wurden.

Autorin:

Dora Derado erhielt ihren M.A. in Kunstgeschichte von der Fakultät für Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaften der Universität Split im Jahr 2016. Sie schrieb sich 2017 für das Graduiertenprogramm für Kunstgeschichte an der Fakultät für Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaften der Universität Zagreb ein. Dort arbeitet sie an ihrer Dissertation: „Provoking Art History: Readymades and Changes in the Perception and Status of Artworks (Reflections on 20th Century Art and Visual Culture in Croatia)”. Sie ist am wissenschaftlichen Projekt zu “Provoking Art History: Readymades and Changes in the Perception and Status of Artworks (Reflections on 20th Century Art and Visual Culture in Croatia)” tätig, das von der kroatischen Wissenschaftsstiftung gefördert wird. Bereits seit ihrem Studium ist sie im Bereich der Kunstgeschichte aktiv; sie organisierte verschiedene internationale Konferenzen und kuratierte Einzel- und Gruppenausstellungen. Dies hat sie vor allem im Rahmen des Crosculpture Projekts fortgesetzt. Ihre aktuellen Forschungsinteressen umfassen Kunsttheorie, zeitgenössische Kunst und Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts, mit einem Fokus auf Bildhauerei. Außerdem ist sie an allem interessiert, was das Vermischen von Ideen betrifft, die diese Bereiche verbinden und zu Kunsttheorien führt, die zum Verständnis von Kunst führen und die sozio-kulturelle Fragen angeht, die sich daraus ergeben.

Diese Arbeit wurde von der Kroatischen Wissenschaftsstiftung im Rahmen des Projekts IP-2016-06-2112 "Manifestations of Modern Sculpture in Croatia" unterstützt: Skulptur am Scheideweg zwischen gesellschaftspolitischem Pragmatismus, ökonomischen Möglichkeiten und ästhetischer Kontemplation".

Die Arbeit der Doktorandin Dora Derado wurde durch das aus dem Europäischen Sozialfonds der Europäischen Union geförderte "Young researchers' career development project - training of doctoral students" der Kroatischen Wissenschaftsstiftung voll/teilweise unterstützt.

Alle Meinungen, Ergebnisse und Schlussfolgerungen oder Empfehlungen, die in diesem Material geäußert werden, sind die des/der Verfasser(s) und spiegeln nicht unbedingt die Ansichten der Kroatischen Wissenschaftsstiftung, des Ministeriums für Wissenschaft und Bildung und der Europäischen Kommission wider.