Sculpture as a reflection of our time

For all those who couldn't attend our Dialogue on 11 July at the Landgoed Anningahof, coordinator Anne Berk will take you on a virtual journey through the beautiful sculpture park and the history of Dutch sculpture since the 1960s.

After first transforming a farm with pastures into a sculpture park in 2004, Landgoed Anningahof in Zwolle, The Netherlands, now organises annual exhibitions. The beautiful park serves as a backdrop for sculptures by established and young artists alike, showing the development of contemporary sculpture from 1960 to the present.

Walking through the sculpture garden offers visual pleasure, and triggers me to philosophize about life. Why do people make art? Why do they do it this way, in these times?

These questions haunted me when I started my training as a sculptor at the Amsterdam University of the Arts in 1982. Thus, I became an author, curator, and coordinator of Sculpture Network.

In the late 1970s, the heyday of minimal art, sculpture was seen as the logical outcome of an action with material, nothing less, and nothing more. In his famous Verblist (1967), Richard Serra (1938, CA, USA) described what you can do with your material: roll, crease, fold, store, bind, shorten, twist, crumple, tear, split, splash, curve, rotate, or suspend, etc. Serra’s Verblist is like a cookbook. Choose one of the 54 recipes and voila, another sculpture. Minimal sculpture was a physical experience in a materialistic, secular age.

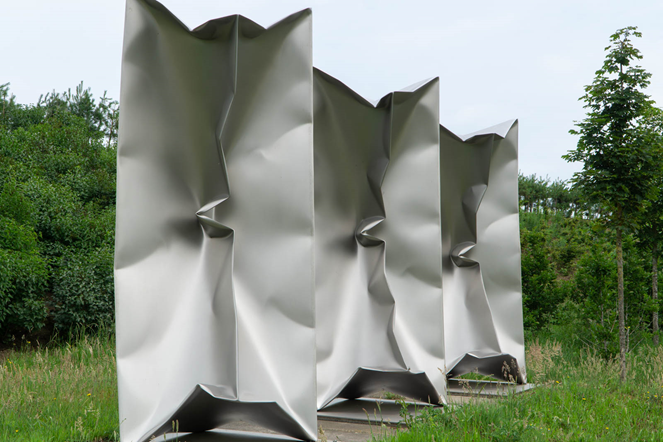

Anningahof contains three impressive sculptures by Serra's contemporary, the German sculptor Ewerdt Hilgemann (1938, DE). His oeuvre consists of metal volumes that are imploded through a secret process of vacuum suction. In doing so, Hilgemann adds another recipe to the Verblist of Serra.

Next to the pond there is another abstract structure, a meters-long concrete piece by André Volten (1925 - 2002, NL). Two long beams enclose a third, which seems to be folded forward. The work consists of elementary, abstract forms of industrial materials, and has no title either.

In minimal art, stories were taboo. That was ballast, which would obscure the view of the art. Minimal art can be seen as the final conclusion of 20th century modernism. In search of renewal, which would herald a utopian new world, the boundaries of art were pushed further and further, until art was stripped to the bone. It was a dead end street. You could only go back. Since the 1980s, artists returned to art traditions and styles from the past, and post-modernism made its appearance.

Escape the Consequenses of Your

In the Netherlands, Henk Visch (1950, NL) was the first to return to the human figure. Trained as an actor, Visch was aware of the gesture's communicative power. With body language, you can tell a story, as artists have done for centuries. In the Anningahof, Visch presents a larger-than-life sculpture of a seated woman. She twists her torso, and turns her face away, as if she wants to hide the blood-red tears that well up from her eyes. You Cannot Escape the Consequenses of Your Own Choice, 2011 is the telling title.

Visch is not interested in abstract objects. This weeping woman questions our behaviour at a time when hopes for a better world have disappeared. Like his contemporaries, such as Juan Munoz, Antony Gormley, Berlinde de Bruyckere, Stephan Balkenhol, Kiki Smith, Lee Bul or Yue Minjun, Henk Visch uses the human figure to ask questions about life. This ‘conceptual figuration’ is primarily narrative, as I described in the book and the eponymous exhibition In Search of Meaning.*

(I Am My Own Prophet), 2016, ceramics,

We live in uncertain, searching times. There are no ready-made answers. You have to find out yourself. That’s the idea behind Anne Wenzel's (1972, DE) I Am My Own Prophet (2018). As if she was anticipating the “Me Too” movement, Wenzel made a series of busts of militant women, inscribed with slogans such as “Fuck the Dictator”, “Resist”, and “Don't Fear Freedom”. These women don't just stand up for their own rights. They demand nothing less than a change in society, but without having a recipe for how to go about it. In addition, Wenzel didn’t spare her heroines. She bruised and scratched them. In her view, nobody is 100 percent good. We muddle on. The series is called Under Construction.

Ivan Cremer (1984, NL) The Birth of Apollo, 2019, scrapwood, metal, photo courtesy the artist

with the Figure of Apollo

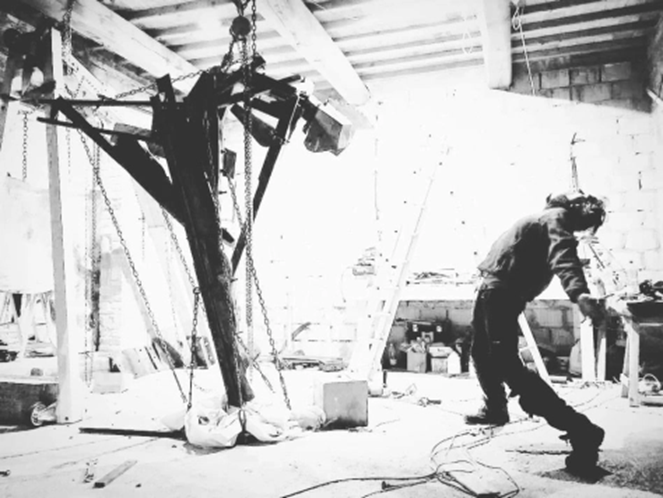

As the human figures of Henk Visch's work, The Birth of Apollo (2019) by Ivan Cremer, (1984, NL) speaks to the viewer's body, but these figures are more light-footed. The attitude of the 9 muses and the god Apollo is based on George Balanchine's 1928 ballet Apollo. See how Cremer empathizes with the sculpture at his studio in Leipzig, Germany to convey the right emotion. Instead of the classic bronze or marble, Cremer recycles found materials to give them a second life.

The number of animal sculptures in the Anningahof is striking. Tom Claassen (1964, NL) made a huge hippo that looks like a toy animal. He first saw the beast in a pool at the zoo. Today we only know animals in captivity, as pets or as cuddly toys. We are alienated from nature and threaten other species. See the impressive dying elephant by Kevin van Braak, which he made with the help of Indonesian woodcarvers.

The youngest generation of artists returns to the formal language of minimal art, but without the serious rigor of modernism. Untitled by Jonathan van Doornum (1987, NL) is a vertical stacking of volumes, reminiscent of an oversized refrigerator. But this work is by no means abstract. Deo Volente—God willing—it reminds us of our vulnerability. Are we in control of life?

‘Art is there to reveal man to himself,’ Henk Visch once said. From the beginning of mankind, people create art to order visual reality and give it meaning. That’s what makes us human.

Anne Berk

Anne Berk is a Dutch curator and author, and coordinator of the European Sculpture Network

She curated many international exhibitions about social themes, such as Liebes Ding - Object Love, 2020 at Museum Morsbroich, Leverkusen, DE; Beyond the Body, 2018 at Kunstcentret Silkeborg, Bad, DK; In Search of Meaning. The Human Figure in Global Perspective, 2005 at Museum De Fundatie, Zwolle, NL; and Bodytalk. The New Figuration in Dutch Sculpture of the Nineties, 2004, at Museum Beelden aan Zee, the Hague, NL. For 2021, she is curateing the exhibition Rettet den Wald for Museum Het Valkhof in Nijmegen, NL.

* In Search of Meaning. Mensbeelden in Globaal Perspectief (The Human Figure in Global Perspective), Waanders, 2015.

Title: Marinke van Zandwijk, Bellenkraan - Building Paradise 5.0, 2020, Wood, rope, handblown glass