Side by Side

On May 25, the Kunstverein Gütersloh opens the exhibition Seite an Seite (Side by Side) with works by sculptors Coral Lambert and Marsha Pels. In order to make outstanding aspects of the content and working methods of the two artists tangible, Berlin sculptor and curator Susanne Roewer has asked each of them two complex questions about the works on display.

On May 25, the Kunstverein Gütersloh opens the exhibition Seite an Seite (Side by Side) with works by sculptors Coral Lambert and Marsha Pels. In order to make outstanding aspects of the content and working methods of the two artists tangible, Berlin sculptor and curator Susanne Roewer has asked each of them two complex questions about the works on display.

Beckoning beyond the physical realm, many of the works in this exhibition symbolize endings and beginnings, exploring the thin veil between opposites such as creation and destruction. The two sculptors, Lambert and Pels, met through working in cast metal, using its power of transformation through dynamic material investigation, yet their outcomes express very different perspectives of the world in which we live side by side.

Q&A with Sussane Roewer, a sculptor and curator based in Berlin. Roewer’s works develop from stories, always triggered by a poetic part of human life and society, absurd or romantic, heroic or stupid, political or stand alone. She is represented in national and international galleries, museums, and art associations. The three artists became fully acquainted when pouring iron together during the Shakers and Makers Cast Iron Sculpture Symposium led by Lambert at the International Sculpture Conference in Miami in 2013. The Q&A took place more recently and is specifically related to works by Lambert and Pels in Side by Side.

SR: In Germany, we have a trend to identify foundries as big enemies for the environment, even when the largest industrial metalcasters like Salzgitter have already done their homework years ago. You get that we feel purified when the steel plants disappear and the still badly needed metal appears by the magic of an oriental wizard. Art and design schools drop their foundry departments since students look for other materials. As the director of one of the largest foundry programs attached to a university in the US and working in a studio in a former steel production city, how do you see the chances of getting a balanced discourse in art and industry when future people will draw most of their experiences from theoretical and digital material?

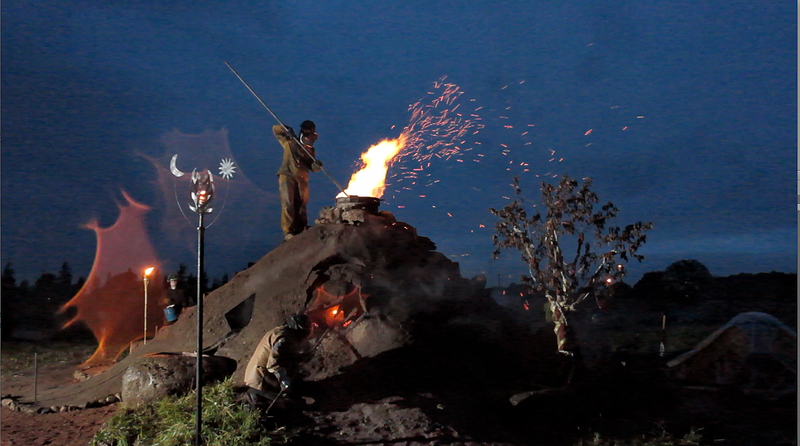

Coral Lambert: Working with a material that is somewhat vilified can be quite poignant and becomes a valuable tool for dialog, especially the art and act of foundry, which teaches us many lessons about the human condition. From industrial foundries to fine art foundries and individual foundry artists, there is a connection with the rich history of metal spanning 5000 years. I see my foundry practice as speeding up the work of nature, referencing mining/stealing, making/labor, and manipulating/copying. For example, my site-specific cast iron performance, Garden of Fiery Delights, reenacted the process of iron casting within the shadow of the dormant furnaces at the Industriemuseum Brandenburg an der Havel. The furnace has symbolic meaning; in alchemy, it was not just a piece of apparatus to heat up and purify metals. “The furnaces were a new matrix, an artificial uterus where the ore completes its gestation.” (Cosmographia 1544). The ore is equated to an animal, hunted, captured, and purified through the process of transformation. Thus, equal to having a human soul, the metal experiences suffering and mortification while being cleansed of its impurities and corruption.

Melting, casting, and dragging the hot, glowing iron along the tracks of the Brandenburg foundry floor, I hoped to bring attention to what came before in the great effort to reap and tame iron from the primordial depths of the earth where it resides. Thousands of tons of weapons for the war effort and railway tracks now spanning the globe were cast on site, and the performance became a memorial of sorts. By engaging oneself and others in the spectacle, we can find balance and an understanding of the value of real-time experiences working directly with processes and materials.

SR: War, abuse, and loss are somehow included in most of your sculptural objects and installations. You cite films and books that triggered and inspired your work. How was your experience with the audience? Are there people from a special region, age, gender, or education with immediate understanding and others who struggle or prefer their own interpretation?

Marsha Pels: Most people have a strong emotional response to my work. Some applaud the irony, some experience disgust. I strive for many interpretations, but only children respond purely. It doesn’t matter what age, ethnicity, or gender they are or what privileges they may or may not have.

Children are unspoiled by any political knowledge. They are pure to respond both visually and tactilely. Because I use found objects, transformed but still recognizable, they understand the ‘content’ and therefore can ‘enter’ the sculpture. I’ve witnessed confusion, curiosity, and wonderment.

As a recent example, my gallery showed Towards Bethlehem in Miami 2021 at NADA/FRIEZE, a cast iron carousel pony sporting a gas mask mounted on a larger than life-size steel hospital walker. I watched parents and their children walk towards our booth. When the parents saw my sculpture, they veered their children away from it, trying to block their view, as if it emitted some noxious odor. But when the children saw it, they immediately ran toward it with delight, trying to climb on it and touching every part.

SR: You will bring some of your iconic Hitler-Vitrines to the show in Gütersloh. For Germans, this might be like bringing coal to Newcastle. Not to forget that a lot of famous German male artists used the citation of Adolf Hitler, and this somehow fueled their careers. Why will it be necessary for a contemporary German audience to see your vitrines?

MP: I made The Hitler Vitrines after my sojourn in Germany in the late 1990’s while on a Fulbright Scholarship to Emden, the town of my paternal ancestors, to research a Holocaust memorial.

I plunged into the German hero worship of the three male Uber Mensch: Beuys, Richter, and Kiefer, and researched how each used Third Reich symbolism. The ‘Wunderkammer’ potential of Beuys’ vitrines as sterilized cabinets of mundane evil, Richter’s Atlas (started 1960’s, first shown 1972), as well as Uncle Rudi 1965, and Kiefer’s Occupations (such as Am Meer 1970) were iconic pieces that I used as a basis for a feminist critique in my post-Emden work. The Hitler Vitrines, The Cleansing, and the accompanying photograph I Like Germany & Germany Likes Me were all directly influenced by the legends of ‘Die Drei Jungen’.

The terror of antisemitic and fascist ‘hate’ groups raising their ugly heads from the shadow of the past 90 years later and infiltrating the contemporary political landscape is not only in Germany but world-wide. There is no space to list why this is so scary. When I was researching the Holocaust in Germany in 1997-99, I was repeatedly asked, “This is ‘unter dem Tisch’ (under the table): why are you digging this up now?” ‘The Hitler Vitrines’ is a historically documented anti-war series made in 2001 by a Jewish American feminist. Unfortunately, it foreshadowed the horror; we are not under the table anymore.

SR: A big part of your work is about material memorials. One of the largest, most contemporary, and most collective architectural projects is The Line. What does a project like this tell you about the future, art, and design? Is the hot discourse about monuments and memorials among sculptors a mouse regarding the permission, possibilities, and power of today's architecture to shape complete regions in a sculptural way?

CL: When we experience monuments such as Egyptian obelisks outside of their intended environment, it brings up questions of ownership, trophies of war, and the relevance of the site in relation to the object. Is it time to return these treasures to their original context and culture? Do we need to replace them, and if so, with what?

The Boobelisk is a tongue-in-cheek proposal to replace controversial obelisks. For example, the obelisk known as ‘Cleopatra's Needle’ in Central Park, NYC, is one twin of a pair, erected in 1881. It was obtained in 1877 by the United States Consul General in Cairo from the Khedive for the USA to remain a ‘friendly neutral’ as France and Britain maneuvered to secure political control over Egypt. Its twin was shipped to London, no simple task as it weighs over 200 tons and stands 21 meters tall. The New York and London Obelisks were originally sited at the entry into the Egyptian city of Heliopolis in 1475 BC.

With the Boobelisk being made of pure cast iron, there is an opportunity here to connect and think about our industrial sites as sacred spaces to celebrate the living, breathing character of iron and rust as a metaphor for life. Installed with sympathetic landscaping to include materials of the casting process such as iron, slag, lava rock, coal, coke, muck, and limestone so that the fabric and history of the ground become fluid and shape whole regions with renewal.

The interview was conducted by Susanne Roewer in English. Thanks to Sybille Hayek for proofreading the texts!