Der weibliche Blick: Voyeurismus neu definiert

Einige gemeinsame Aspekte weiblicher Erfahrung werden – wenn auch nicht immer ausgesprochen – doch kollektiv verstanden. Voyeurismus, oder vielmehr der männliche Blick (male gaze), der wahrscheinlich seit Beginn der künstlerischen Entwicklung des Menschen existiert, ist ein solches Phänomen.

1975 erhielt es auch einen Namen: Als Laura Mulvey ihren Aufsatz "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema" veröffentlichte, schuf sie einen Spitznamen für eine ererbte soziale Konditionierung der Generationen von Frauen vor ihr, die im traditionellen Kunstkanon dominierend präsent sind:

„In einer Welt, die von sexueller Ungleichheit bestimmt ist, wird die Lust am Schauen in aktiv/männlich und passiv/weiblich geteilt. Der bestimmende männliche Blick (male gaze) projiziert seine Phantasie auf die weibliche Figur, die dementsprechend geformt wird. In ihrer traditionell exhibitionierenden Rolle werden Frauen gleichzeitig angesehen und zur Schau gestellt, ihre Erscheinung ist auf starke visuelle und erotische Wirkung zugeschnitten. Man könnte sagen, sie konnotieren `Angesehen-werden-Wollen‘.“

Im Anschluss an die Veröffentlichung dieses Textes fand in der zeitgenössischen Kultur eine zunehmende kritische Beschäftigung mit dem Voyeurismus statt, die verschiedenartigste Formen der Reaktion bei Künstler*innen hervorrief. Eine der Ausprägungen ist die künstlerische Entwicklung des weiblichen Blicks.

Der weibliche Blick oder weibliche Voyeurismus stellt allerdings keine dem männlichen Blick generell entgegengesetzte Sicht dar. Vielmehr handelt es sich um einen Wandel in der Art und Weise, wie Frauen in traditionellen künstlerischen Werken wie Skulptur, Porträt oder darstellender Kunst gezeigt werden, der einzig und allein von der Künstlerin bestimmt wird.

Der weibliche Blick will lenken, in welcher Art die weibliche Form oder das weibliche Subjekt zur Freude des Betrachters sexualisiert oder verwundbar gemacht wird.

Das Werk der in Italien geborenen amerikanischen Künstlerin Vanessa Beecroft ist eines der frühesten Beispiele für weiblichen Voyeurismus. Der Fotograf Phillip Schorr beschreibt ihre Arbeit folgendermaßen: "Beecroft interessiert sich für die weibliche Ästhetik des Angesehen-werdens. Die Körperlichkeit ihrer Projekte erzeugt bewusst eine Entfremdung zwischen Modell, Künstlerin und Publikum. Ihre Performances, Gemälde und Skulpturen sind schonungslos konfrontierend und fordern die Zuschauer*innen auf, ihre aktive, voyeuristische Rolle zu reflektieren.“

Beecrofts prominenteste Werke zeigen nackte oder fast nackte Frauenfiguren, deren Inszenierung meist in Stil und Pose die Ästhetik des Militärs oder der Modeindustrie übernimmt, während sie stetig und direkt den Blickkontakt mit den Betrachter*innen halten.

Mit Ihrer Art der Annäherung an das Voyeuristische äußerte die Künstlerin Kritik am globalen Krieg, an der Mode- und Unterhaltungsindustrie und ihren Anforderungen an den weiblichen Körper sowie an der Annahme des männlichen Blickes als Norm, wie er in der westlichen Kultur von den 1990er Jahren bis heute akzeptiert wird.

Die zeitgenössische Fotografin Nona Faustine arbeitet ähnlich konfrontativ, wobei sie sich auf die Komplexität ihrer Erfahrung als afroamerikanische Frau stützt. In ihrer Serie WHITE SHOES fotografiert Faustine sich selbst nackt an verschiedenen Orten in Brooklyn, NY.

Jedes Foto zeigt ein Über-Bewusstsein ihrer Verletzlichkeit, die nicht zuletzt aus ihrer Erfahrung mit Misshandlung als schwarze Frau in Amerika resultiert. In "Like A Pregnant Corpse The Ship Expelled Her Into The Patriarchy" (Wie eine schwangere Leiche hat das Schiff sie in das Patriarchat vertrieben) liegt sie ausgestreckt auf einer Felsbank der Atlantikküste. In "Of My Body I Will Make Monuments In Your Honor" (Aus meinem Körper werde ich Denkmäler zu Euren Ehren errichten) steht sie auf einer Seifenkiste auf dem vorrevolutionären Friedhof in Brooklyn auf dem neben frühen Siedlern auch drei Sklaven begraben sind. Das erste und wohl dominanteste Bild der Serie "She Gave All She Could And Still They Ask For More" (Sie gab alles, was sie konnte, und trotzdem wollten sie mehr) verweist auf den ständigen Druck auf Frauen, die (männlichen) Erwartungen an Körperästhetik, Sexualität, Verhalten und Kultur zu erfüllen.

In jedem dieser Bilder ist Faustines Gesicht entweder versteckt oder verzerrt. Ihr nackter Körper wird so, ganz den traditionellen männlichen Blick spiegelnd, zum einzigen Bildsujet. Während die Künstlerin mittels der gewählten Titel und historisch aufgeladenen Orte, Kritik an Rassismus und Sexismus übt, kontextualisiert sie ihr ihr Werk in der Art der Selbstdarstellung als weiblichen Voyeurismus. Mehr Werke der Künstlerin finden Sie hier.

Eine weitere Annäherung an den weiblichen Voyeurismus liegt in der Verzerrung der traditionell kuratierten, westlichen Ästhetik der Präsentation des Weiblichen als "begehrenswert“.

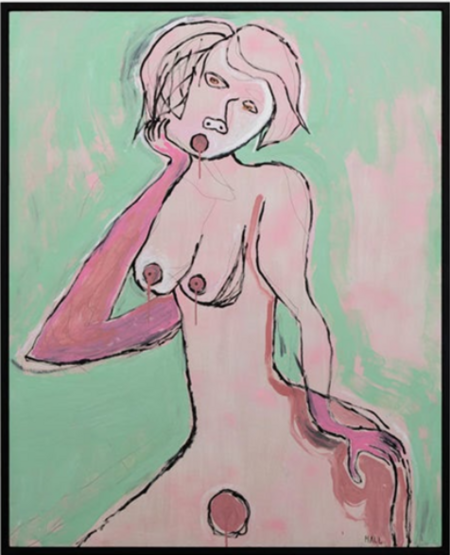

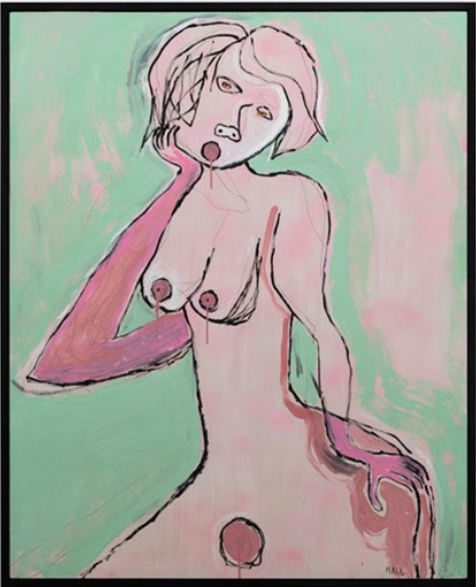

Die multidisziplinäre Künstlerin Trulee Hall versucht mit Tropen des Mulvey‘schen „Angesehen-werden-Wollens“ und einer konfrontativen Performance-Qualität à la Beecroft das Verständnis des Betrachters von weiblicher Sexualität zu verändern.

Im Gespräch mit Janelle Zara für das Art Basel Magazine, erklärt Hall: "Wir [als Frauen] sind darauf konditioniert worden, sexy zu sein, aber nicht zu sexy". Die weiblichen Figuren in ihrem Werk sollen als "unangenehm, irgendwo zwischen peinlich, unbehaglich und sexy" wahrgenommen werden. Ziel ist die Verwandlung der Erfahrung des Betrachters vom schuldigen oder nachsichtigen Voyeur in einen kognitiven Beobachter und Verfechter der ehrlichen weiblichen Erfahrung von Sexualität und Verletzlichkeit.

der Ausstellung Other and Otherwise,

Maccarone Gallery, 2019.

Gemeinsam in ihrer Herangehensweise an den weiblichen Voyeurismus ist Beecroft, Faustine und Hall neben zahlreichen anderen Künstlerinnen: Ihre Arbeit hat das Potenzial, Männer zu erziehen und Frauen eine Befreiung von ihren traditionellen Rollen in der Kunst und im Leben zu ermöglichen.

Diese Künstlerinnen führen den weiblichen Blick mit der Absicht, Frauen eine visuelle Darstellung zu bieten, mit der sie sich identifizieren können, und die gemeinsame Erfahrung von Frauen als Objekte des ästhetischen Vergnügens in traditionellen künstlerischen Praktiken anzuerkennen.

Während sich die akademische und kulturelle Interpretation des weiblichen Blicks weiter entwickelt, wird sich auch der gesellschaftliche Diskurs um die Darstellung des weiblichen Subjekts fortführen - zum Wohle von Betrachter*innen jeden Geschlechts.

Die Autorin

Die in Los Angeles lebende Künstlerin Chelsea McIntyre arbeitet in den Bereichen Skulptur, Text, Performance, Digital und Mixed Media. Ihre Arbeit wird durch Elemente der objektiven Psychoanalyse, der Institutionskritik, des russischen Konstruktivismus und des materiellen Fetischismus und Voyeurismus geprägt. Ihr besonderes Interesse gilt der Erforschung der die menschlichen Psyche und der Beziehungen zwischen Künstlerinnen und Künstlern und ihrem Publikum. Mehr über Chelsea und ihre Arbeit erfahren Sie hier.