Deutschland

Michael Lukas

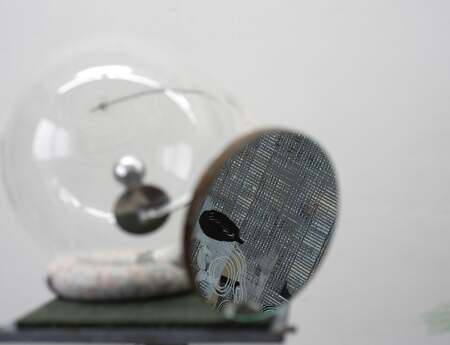

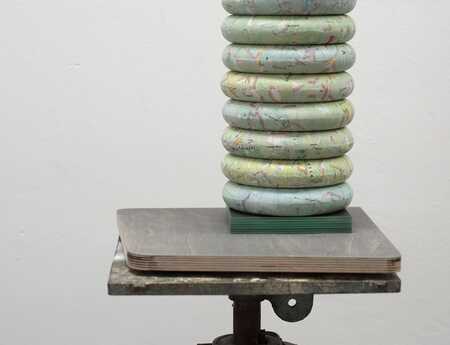

Michael Lukas / occupied corner, 2016 Dr. Magdalena Wisniowska

Just as there are two ways of interpreting the aesthetic object, there are two ways in which the work of Michael Lukas can be approached. If we take the perspective prior to aesthetic experience, the work becomes the object of our study. We begin by situating the work and cataloguing its numerous themes. These include but are not limited to the fields of ontology, topology, geography, social science and history. From the perspective of aesthetic experience however, we need to examine the kind of experience the work engenders, which I would argue is unique. Perhaps the term aesthetic experience is misleading as Michael Lukas’s work involves much more than the traditional sense of the term, with the object to be viewed by the human subject, the individual artwork to be judged by the art expert, the connoisseur. Michael Lukas’s work presents a problem: in Deleuze’s words, it forces us to think.

The site-specific work we see at GiG Munich does not exist as the one or even the group of paintings, what we know as compositions of brushstrokes on wood or canvas. It consists of the relations and connections these material elements make with each other, with other paintings, with the artist and with us, the viewer. The relations are physical but also abstract or intellectual, the connections between nebulous ideas just as important as those made by objects in Euclidean space. In other words the painting installation of Michael Lukas stages an encounter, an encounter always being the confrontation between a set of forces. The result of the encounter is an assemblage of affects.

For Spinoza, who is my main reference point here, the forces set up in the encounter have two possible outcomes. The encounter results either in the increase of the capacity for action, which is perceived as pleasurable, or in its decrease, which is felt as pain. The assemblage of affects is the consequence of the first kind of encounter, the pleasurable composition of relations, which ultimately is to bring us knowledge of God. Deleuze complicates matters by insisting that in the encounter, the position adopted by the body is one of combat. In combat, forces struggles against each other, going across and breaking up the organized body, as set within its boundaries. For combat to be considered by Deleuze as a positive encounter, this struggle cannot be resolved with the dominance of one force over the others. Any kind of resolution compromises combat’s inherent creative element. Something new is only produced when the struggles of the forces is maintained.

Michael Lukas’s work keeps up this tension, this struggle between various forces. He uses the frame, a repeated motif in his paintings and physically manifest as a sculptural relief hanging in the gallery corner, to demand from us the move out of an organized framework – to shift from one material aspect to another, to make those intellectual connections we would otherwise not make, all the time preventing us from ever settling on the one object, the one image, the one idea. When encountering Michael Lukas’s work, we are forced to think, in that we are forced into a position of creativity. It spurs us to action. But it never allows this activity to be resolved. We are continually intrigued, looking, making sense, thinking. 2016

Just as there are two ways of interpreting the aesthetic object, there are two ways in which the work of Michael Lukas can be approached. If we take the perspective prior to aesthetic experience, the work becomes the object of our study. We begin by situating the work and cataloguing its numerous themes. These include but are not limited to the fields of ontology, topology, geography, social science and history. From the perspective of aesthetic experience however, we need to examine the kind of experience the work engenders, which I would argue is unique. Perhaps the term aesthetic experience is misleading as Michael Lukas’s work involves much more than the traditional sense of the term, with the object to be viewed by the human subject, the individual artwork to be judged by the art expert, the connoisseur. Michael Lukas’s work presents a problem: in Deleuze’s words, it forces us to think.

The site-specific work we see at GiG Munich does not exist as the one or even the group of paintings, what we know as compositions of brushstrokes on wood or canvas. It consists of the relations and connections these material elements make with each other, with other paintings, with the artist and with us, the viewer. The relations are physical but also abstract or intellectual, the connections between nebulous ideas just as important as those made by objects in Euclidean space. In other words the painting installation of Michael Lukas stages an encounter, an encounter always being the confrontation between a set of forces. The result of the encounter is an assemblage of affects.

For Spinoza, who is my main reference point here, the forces set up in the encounter have two possible outcomes. The encounter results either in the increase of the capacity for action, which is perceived as pleasurable, or in its decrease, which is felt as pain. The assemblage of affects is the consequence of the first kind of encounter, the pleasurable composition of relations, which ultimately is to bring us knowledge of God. Deleuze complicates matters by insisting that in the encounter, the position adopted by the body is one of combat. In combat, forces struggles against each other, going across and breaking up the organized body, as set within its boundaries. For combat to be considered by Deleuze as a positive encounter, this struggle cannot be resolved with the dominance of one force over the others. Any kind of resolution compromises combat’s inherent creative element. Something new is only produced when the struggles of the forces is maintained.

Michael Lukas’s work keeps up this tension, this struggle between various forces. He uses the frame, a repeated motif in his paintings and physically manifest as a sculptural relief hanging in the gallery corner, to demand from us the move out of an organized framework – to shift from one material aspect to another, to make those intellectual connections we would otherwise not make, all the time preventing us from ever settling on the one object, the one image, the one idea. When encountering Michael Lukas’s work, we are forced to think, in that we are forced into a position of creativity. It spurs us to action. But it never allows this activity to be resolved. We are continually intrigued, looking, making sense, thinking. 2016