Fernando Casasempere

Fernando Casasempere (b. 1958, Santiago de Chile, lives and works in London) works with clay, ceramics and industrial matter, redefining the possibilities of these materials for contemporary sculpture. Through a fascination with the imprint left by humans on the earth, Casasempere draws on archaeology, geology, landscape and classical and modern architecture to subvert sculptural archetypes, while speaking to urgent global ecological and social concerns through the lens of his native Chile.

Following a busy year - including the solo exhibitions Terra at the San Diego Museum of Art and Scratching the Surface at Bloomberg SPACE, a selection for the Loewe Prize shortlist from more than 3,000 entries, and the unveiling of two major new commissions at Henrietta House and Soho Place - I had the pleasure of interviewing Fernando in his studio in Hackney to discuss his practice, his relationship with sculpture, and why it is a medium so suited to addressing some of the most urgent societal and ecological issues of our time.

Your work deals with some of the most pressing issues of our time, including climate change, extractivism and our relationship with the earth. In what ways is sculpture a useful medium to address these issues? What can sculpture offer us now?

Well, I always say, more than the sculpture it’s art that has the privilege to have a voice - like now, with you interviewing me. And I think art needs to speak to these very important issues to raise awareness. I’m a more three-dimensional person, so I think in some ways sculpture chose me, and then I chose sculpture to talk about these issues. But I think it’s something about the presence of sculpture, and the possibility that three-dimensional objects give you. Because you can be involved: like with some of the rooms in my recent exhibition Terra at the San Diego Museum of Art (2022). You walk through the idea, you are involved in the idea. And I think that helps much more, it creates resonance, because it’s a physical thing - there’s a physical response. Which is why I always say, when people are complaining about graffiti in town - I think it’s because it intercepts people’s paths as well. And that’s what sculpture is about too. It’s a physical presence and then people can really interact: they either need to avoid, or confront it. So, you can really put people in front of an idea, or immerse them in it, in a way that is perhaps less direct with other media.

You often draw a comparison between geology and your work as an artist. I’d love to hear more about this.

It’s funny, because I’ve been thinking lately about why geology is so important for me. I’m a guy from a country with the biggest earthquakes on planet earth unfortunately. I think there are over 40 living volcanoes in Chile. This presence of geology, of the melted material inside the volcanoes, the aliveness of the earth, has been with me and has been a part of me since I was born. When you live in Chile you’re always hearing about the tectonic plates, the American plates, there’s a plate in the centre of Santiago, so we’re incredibly connected to all of that. And what is the connection with what I’m trying to do? I think the most similar understanding Europeans might have is with fracking. What comes to your mind when you think of fracking? It’s what’s underneath, the core, the damage that happens inside. We are damaging and breaking the earth, and the earth trembles in response. When I think about fracking, I have the same feeling as when I’m thinking about tectonic plates, or the earthquakes in Chile. It immediately transports you to the core of the planet.

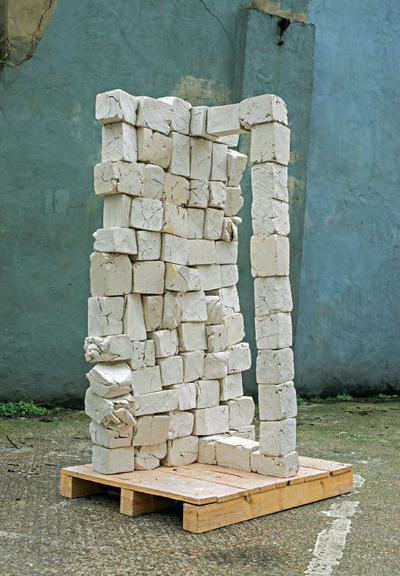

Volcanoes are the greatest ceramicists - because the power of fire melted inside is concentrated in all this magma, which is no more than all these minerals that come from the heat from the centre, from the core of the planet. And from time to time, the volcano explodes, it sends it all out, and when it freezes and consolidates it becomes a new material, a new rock, a new mineral. And that’s what we do with ceramics as well, somehow - my new work around the corner from Tottenham Court Road station is called Geology Rebuilt (2022). As a sculptor working with ceramics, I pulverise all these minerals into a mix, but they still have iron and all kinds of components, and I then put them reconfigured, into the fire. Then, when the kiln is cold, that mix becomes something else, it becomes this new geology, this new material. Which is why I compare what I do with volcanoes, why I say all the time that they are the best ceramicists in the world.

Your practice reflects a profound connection with the landscape of your native Chile, and it manifests materially in the works that you make. I’d love to hear about your clay mixes, and what first prompted you to use waste matter in them?

Since I started working with clay, I made a very conscious decision: I wanted to belong to the masters of my continent, to pay my respects to the Native American masters of my continent. I wanted to make clay talk, and to talk in a really contemporary way and to go to the limit of the medium. And that’s why it’s such a joy for me to make works like Geology Rebuilt (2022) or other large projects, because they really push you to the limits of what is possible. In order to achieve these kinds of ideas, you need to remake and rethink, to try to make the impossible happen - for example, a 200kg solid block of porcelain was supposed to be impossible, and it’s done. In order to do that, I have to do thousands of tests - testing not only the materials, but also the temperature of the kiln, how fast it can rise or fall, all of that. In 1991 it all started when I received a scholarship to study new materials and incorporate these in the clay. And then I traveled in Chile, and, you know, Chile is a mineral country: we are rich in copper, iron, lapis lazuli and lithium. We are very blessed in that way, but now with a new consciousness we need to approach these materials in a different way. And I thought, those materials are already so well-known. What if I use the waste, the sub-product of extracting those minerals, the consequence of extractivism, in order to play a part in reframing the conversation around our collective responsibility to come up with solutions for the climate crisis.

Could you speak a little more about the issue of extractivism in Chile, and how it affected your work and practice?

It’s an enormous question, and I think it’s a very different view to that of people living in so-called developed, first-world nations. To understand extractivism in Chile, I think it’s also important to contextualise it: we are one of the countries with the lowest environmental impact on the earth, and we are one of the countries that is going to be most affected by climate change. So can we afford not to extract, not to use what we have? What are the social implications of that, in terms of poverty, and the resulting lack of resources to fund education, with all the consequences that would bring? For me, the word is: cooperate. Raise awareness, and find better, more climate-efficient methods. But first of all, I think first-world countries need to reckon with the damage they have done to the planet. We need to find a balance, and I hope talking about it, and answering questions, might make room for real conversation.

Well, there’s a huge ecological paradox - we’re trying to move to a green, renewable-led, battery-powered future to replace oil and gas, but of course those batteries operate with minerals, which have to be mined to power this green revolution. And those processes are likely to have devastating environmental consequences, and also damaging social consequences to communities. So how do we move away from oil and from gas - which we absolutely need to transition away from - and find new alternatives without repeating the errors of the oil economy?

Yes! And the main conversation and where we need to go is really towards a new movement, where we need to do less, produce less. We need to make long-lasting, high quality things where we don’t need to replace things every 5 years, or every 10 years. In the 1950s, home appliances worked for twenty years. Now planned obsolescence is factored into everything - otherwise capitalism, which is the cancer of the planet, also won’t grow. So it’s about that as well - de-growth. Allow poorer countries to develop mindfully, but also think of a new approach where larger, richer countries are not abusing the planet.

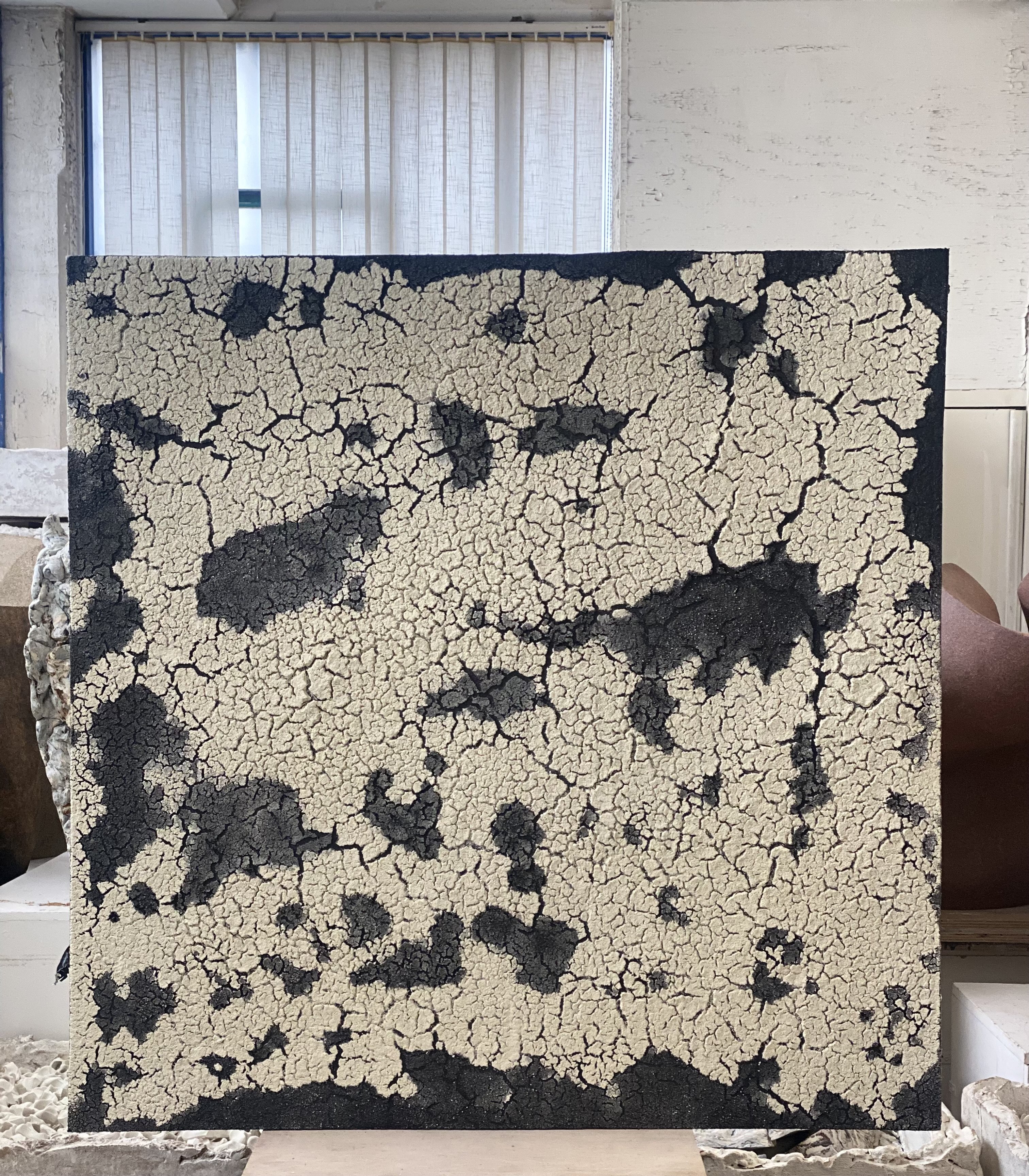

Going back to sculpture: some works, such as those in your wall-based Salares series, push the limits of what is possible with materials like clay, and with it, the parameters of what we perceive and recognise as sculpture. Could you tell me more about your experimentation across two and three dimensions?

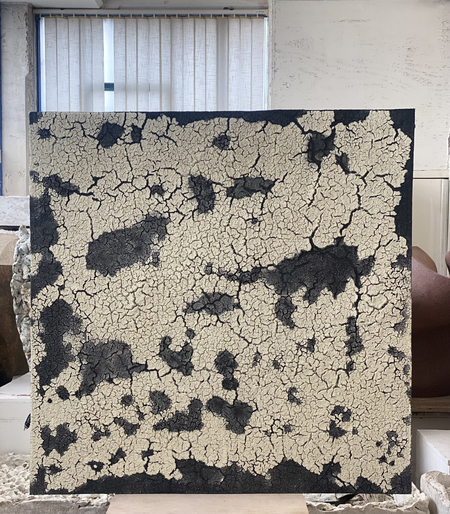

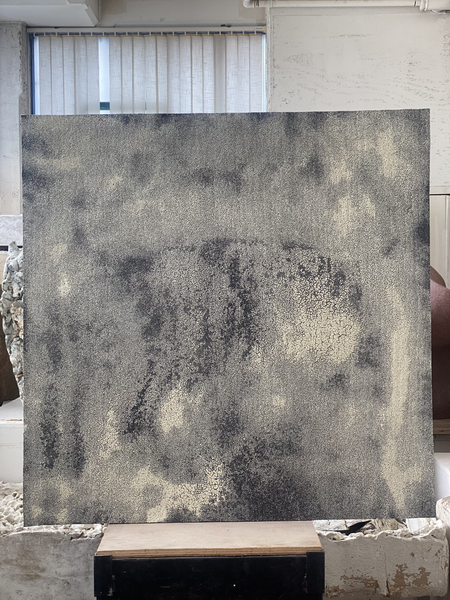

First of all I’m an artist, and as an artist I need to research and to move forward and change. I want to make my material talk. So I use raw clay to do something new, and I want to use the clay in the most expansive way possible: raw clay, porcelain, stoneware, low temperature clay, glazed and unglazed. And secondly, given how much of my inspiration is the landscape of my country, I want to talk about the salt flats, I want to talk about the surface of the planet, not just the geology, not just the core or the inside. So those were the main motivations for me with this series, as well as to try to explore in two dimensions. Moving in some way into the realm of painting enriches my work as a whole, and of course makes me quite excited to get up in the morning to try something new.

Fernando Casasempere, Salar, 2022. Clay and India ink on felt

And like you say, moving into an almost painterly dimension enriches the sculptural process, because it challenges what sculpture can be.

Exactly - and honestly, you can see through that series how sculptural I really am, because my “painting” as such is very material, and although it is two-dimensional, it is layered and thick, and there’s the materiality of both felt and ceramics. Matter, and materials, have really attracted me since I was ten years old. Whenever I went to the museum I would stop in front of paintings that were by Tàpies and artists like him, you know? Incredibly rich in material.

Yes! He’s such a good example of an artist whose paintings were almost more like sculptures than paintings. And in a related vein: ceramics are not normally associated with sculpture, and have historically been relegated to the realms of craft or design. How did your interest in ceramics begin, and what made you turn to this material to produce your sculptural works?

Everything started while I was growing up, seeing pre-Columbian art. For me it was unbelievable material, to see what they achieved. But then, the most interesting thing is, the indigenous peoples of the Americas didn’t have a problem with the distinction between a vessel and a sculpture. For them, a vessel is a sculpture in itself. They made faces on vessels, or zoomorphic shapes, they made portraits of their people on the vessels - the Incas as well as the Mayas. So I have never been able to, and would never separate the sculpture from the pot. For me these two are kind of together. The challenge for me was to do something different. I can pay homage to them, but with my own sculptural language. I am obviously not indigenous, but I have enormous respect for their aesthetic traditions and feel like I have so much to learn from those visual languages. Much of what they were doing such a long time ago hasn’t been accomplished in contemporary art. And when I decided to study art and went through a process of intellectualising everything, I realised I belong to those traditions - not to the white marble I was studying. So it reinforced my idea of the importance of ceramics, and how I should approach sculpture.

To that point - artists working with sculpture often turn to classical European traditions for inspiration. Instead, you really celebrate pre-Columbian art in your practice. I would love it if you could tell me more about some of the influences that have led you to develop your aesthetic.

Yes, pre-Columbian art is one of my greatest influences. But when you talk about pre-Columbian art in Latin America, it’s a political issue. Indigenous people in the south of Chile have been protesting to reclaim their land, and to be recognised in the constitution. People outside of that sphere are not keen to address the indigenous roots of the country, and even to recognise the rich artistic heritage we have from the indigenous people of Chile. People feel uncomfortable. And that is one of the biggest mistakes. So I deliberately want to talk about pre-Columbian art, and the enormous impact it has had on my practice, because we need to recognise these traditions. Indigenous peoples are masters in art, and in many other things - in their approach to health, and how they use the planet: we need to learn from indigenous people.

And one thing that’s amazing about pre-Columbian art, which I learned when I studied it, is that it is one of the purest forms of expression in the world. Because at the time, they had no knowledge of other civilisations. For example, the Mediterranean civilisations knew about other civilisations. And one of the best examples is Venice - with its crossover with the Byzantine empire, and Roman influences. But the art of the pre-Columbians was so unique because it came only from them. I was in awe when I learned that. But when I started studying ceramics I thought I had to leave Chile, because ceramics is not something you learn or do in Chile, for many of the same reasons. And anything connected to indigenous practices is still seen as lesser than in Chile and it’s not celebrated, and not taught. So the consequence is we don’t have a very good school of ceramics in Chile. I felt like I needed to leave Chile, but at the same time I didn’t want to study much of European art because I didn’t want to be influenced during that time. Then when I moved away from Chile, later on I started to bring in some European references. But the resonance of pre-Columbian art is on my mind all the time.

Clay seems to be making a comeback in the world of contemporary sculpture, and contemporary art more widely - why do you think that’s happening at this particular point in time? Why is there such renewed interest in clay?

I think it’s because the art world is reviewing itself, reckoning with itself. You know, I think for a long time that material, and the artists working with it, felt somewhat relegated. And historically mediums have been relegated in art history - as have people. Look for example, at what has happened with the female gender. Suddenly the art establishment realised the importance of female artists and the unfairness of the history of art without women. I think the recognition of clay now, is part of a revision. And I hope that it truly is a review in earnest, and not just a market trend, which happens a lot in the art world and can be quite dangerous.

Fernando Casasempere, Vessel (ripple), 2019. Courtesy of the artist

You’ve previously talked about the pot - that most elemental piece made by ceramicists - as your version of a watercolour. I love that analogy - can you tell me more about that?

Well, like I always say, there’s a feeling that we need to defend or justify ourselves all the time regarding the distinction between art and craft, and I feel like in the past that defense wasn’t very convincing, people weren’t very invested in defending the material and its dignity. If a painter touches on all aspects of their medium, the total body of work is going to be much more interesting. And for me it’s exactly the same, and it’s what I want to do with my practice. I experiment with temperatures, with scale, I’ve made tableware, everything. We don’t think about it all the time now, but it was an enormous step for civilisation when humans made the dish, which separated the food from the earth: fewer illnesses, fewer infections. Why don’t we celebrate and honour that? And that’s why I say that the pot is my watercolour. Don’t ask me if I’m a ceramicist or a sculptor: I work with clay and I want to explore every aspect of it. My sculptural blocks, which are large pieces, and weigh a ton - with these works I’m talking about bricks! About bricks and mortar, and other very important applications of the materials. Bricks are ceramics, and I’m not ashamed to make that connection explicit.

These binaries between ceramic versus sculpture, art versus craft - they’re not particularly useful any longer, they’re incredibly reductive.

I agree. The line for me is the quality. What I might be embarrassed by is a bad pot. Or a bad sculpture. And one thing hasn’t been touching, or connecting with the other. We’ve been quite shy to explore the endless possibility of clay. And I think when people start to do that, the art ecology responds to it. Because it’s about breaking boundaries, about going further. Like when Michelangelo said when he smashed the nose of one of his too-perfect sculptures, and said to it “talk!” That is our challenge and that is our duty. To make the material talk, and to talk in different ways.

Your series Vessels (Organic forms), which includes works like the one shortlisted for the Loewe Prize this year, is not necessarily anthropomorphic, but bears a direct correlation with the body. How do you make these works? What do you think sculpture can add to our understanding of space, and of our bodies in space?

For these works I make a big balloon, each one has a different shape, and then when the consistency is correct I use my own body and then I start to compress the clay, and then to carve it: I make a curve deeper, or exaggerate the part where a part of the balloon comes out into the space. That’s when the conversation between the artist and the piece begins. And I’m still developing these pieces, because I really enjoy them and there’s a lot there to be discovered. This perfection or mix between the utilitarian, and the resonance of vessels and sculpture, and the perfection when you use the body. There’s something about the scale of the body that makes the proportion almost perfect. And that I like very much. And at the same time, when you use your body, I try to achieve almost the relationship the body has with a handle. Or like in sculptures of saints, where people touch the sculpture in a specific place, and make a mark and the patina is gone. It’s kind of the same, when you touch the handle of a vessel or a jar - there’s direct contact, a direct relationship between your body and the piece.

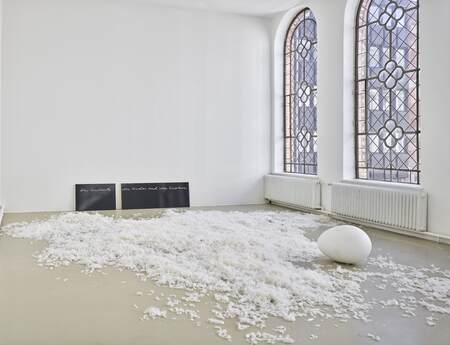

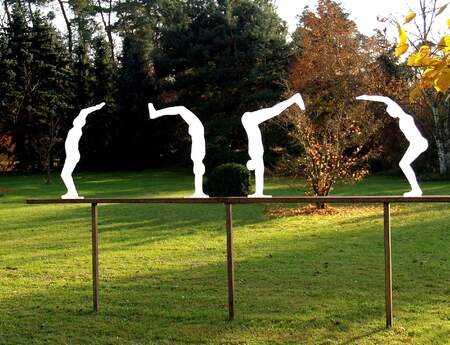

Your work oscillates between large-scale installations - like Out of Sync (2012) at Somerset House, or your monumental installation at the Bellas Artes Museum (2016) in Chile, as well as Murmurations (2022), a piece recently installed at Henrietta House in London - and small, intimate works. Often your largest sculpture is made up of tiny individual components, many small pieces that make up a whole. What do you enjoy about playing with scale?

I both enjoy it and it’s a process where I'm learning at the same time. Because when you work on these very intimate small pieces, like a cube of 10x10cm, I notice how painful the back of my neck is while I work! You really are in that piece, it’s in your hand, so the approach is completely different. And then I remember when I was making the piece for Somerset House (Out of Sync, 2012), which was composed of 10,000 individual ceramic flowers, I had a kind of lightbulb moment - I was treating every piece like a unique work up until then. But then I thought, I have to think about the total, about the whole: so I started to perforate each flower in different directions to add a stem to it, so that as a group, there’s movement. And these moments are enormously enriching for my practice. And it’s funny, I always say, every material has its own size. For example, a watercolour that is 2m x 4m - you rarely see that, I’m not sure it exists. And I think it’s because the material has a voice, each material has a scale. It’s the same with ceramics - that is the logic of the brick. You can multiply the elements to create scale. The technicality of the kiln, the scale it allows for, all of that needs to be in consonance, or in conversation with the material.

I like working on both large and small sculptures. These monumental pieces, these large scale works, normally come out of a commission, or an invitation. What I like about that is that they put you in a position you never expected. Like with Somerset House - I never, in my entire life, thought I would make flowers. And I did. Because flowers are a very charged subject - like painters trying to paint a ray of light. But for that specific place I thought that was the best thing to do, to use flowers to talk about what I wanted to address: an earth, and a climate that is out of sync. So it’s really interesting when you’re placed in a completely different scenario to that of your regular practice. And then also how people respond to it, because it’s definitely more public, and that’s also very interesting to see. But I also like the intimate works - when I do these enormous projects, which sometimes take a couple of years, I start to miss my other work in the studio! Everything enriches everything else, that’s how I think about it.

When you’re making the components of an enormous piece, like your work at Somerset House - what is that process like psychologically? It involves a lot of repetition, and I wonder whether you experience it as a kind of meditation?

It’s definitely like a kind of meditation. I like that continued repetition, and in a way it’s when I was exploring with that in the studio that I had such a lightbulb moment, and it changed my entire idea for that particular installation (Out of Sync, 2012). That’s the kind of silence and meditation you go into when you’re repeating these little pieces to make a larger whole. And I think because I was doing that, I realised, it’s not about the flower - it’s about the total meadow.

What are you working on now in the studio?

The past year has involved a lot of traveling, with lots of visibility for my work, including a large solo exhibition at the San Diego of Modern Art (Terra, 2022). I’m grateful for all the opportunities, but I’m also missing my routine, my time in the studio, to follow through with the thread of an idea. So I’m making new pieces now. I’m pursuing existing threads but in completely different ways. I recently tried to make a new colour with the clay. For me one of the most interesting things is the dialogue with the material, and the way that in ceramics, the colour and the texture help you to transmit an idea. I feel like an artisan, if I do the same thing again, and again and again. Of course you have to stop and develop an idea until you master it. But let’s say, I feel more connected with Ai Wei Wei than with other artists - in the sense that he’s always experimenting, but in completely different ways: from the bicycle sculptures, to the sculptures with furniture…I really like that, and I really like seeing work by artists like him. I feel a kind of kinship with him, but the difference of course is that I only use one material, and explore all its different facets: that is my challenge.

About the artist:

Casasempere has exhibited extensively and his work is in collections including the Victoria & Albert Museum, London; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Harvard Museum, Cambridge; Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam; Contemporary Art Museum, Osaka; Musée des Arts Decoratifs, Paris; International Museum of Ceramics, Faenza. His internationally renowned installations include the critically acclaimed Out of Sync (Somerset House, London, 2012) and Back to the Earth (New Art Centre, Salisbury, 2005). Selected exhibitions include: Solo: San Diego Museum of Art (2022); Bloomberg SPACE (2022); Seoul Museum of Craft (2022); Casa America, Madrid (2020); Ivorypress Gallery, Madrid (2019); Parafin Gallery, London (2018); Tomio Koyama Gallery, Tokyo (2017); Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Santiago (2016). Group: Frieze Sculpture Park, London (2016), Sculpture in the City, London (2016), Sotheby’s Beyond Limits, London (2008), New Art Centre, Salisbury (2008), Jerwood Foundation, Alcester (2007).

Author: Inês Geraldes Cardoso

Inês is a curator and writer based in London, and works closely with artist studios on curatorial projects, production and development strategies. Her research interests include ecology, land art, feminism, new materialism, language, fiction and text in art. Her practice draws on her background in Art History and Social Anthropology from the University of St Andrews. She is a graduate of the MA in Curating Contemporary Art from the RCA, and has collaborated with institutions including Folkestone Triennial, UP Projects (London), Create London, Bluecoat (Liverpool), Kunstverein Munich, Toronto Biennial, Kai Art Center (Tallinn), Art Night (London), The London Contemporary Music Festival (London), Open Space (London), MeetFactory (Prague), SitxtyEight Art Institute (Copenhagen), Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo (Turin), the Curatorial Program for Research (Baltic Sea), and Kunsthalle Lissabon (Lisbon).